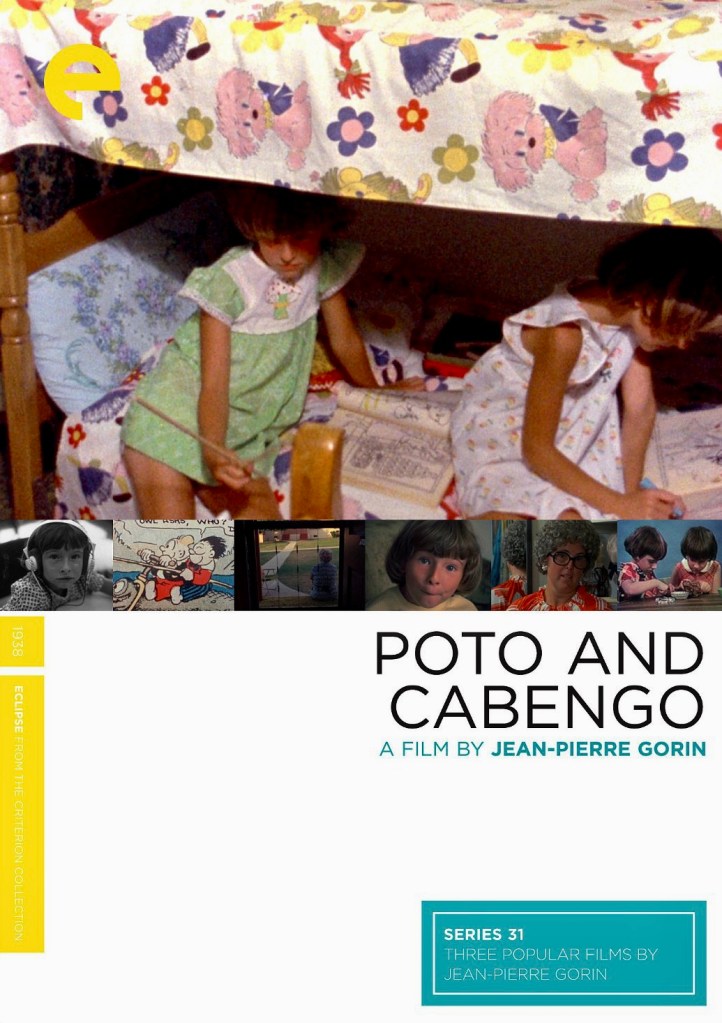

In 1977 journalists became fascinated with a story about six-year-old twin sisters in San Diego who spoke in a language no one could understand but was the sole means of communication between the two girls. Their names were Gracie and Ginny Kennedy but they called themselves Poto and Cabengo in their nonsensical form of speaking. Had they actually created a secret language for themselves or was it just meaningless blather? The girls became a media sensation and speech therapists at the Children’s Hospital in San Diego studied their language in hopes of determining whether the girls’ interaction was a case of arrested idioglossia, a phenomenon in which twins (or individuals) create a private language with a unique vocabulary and syntax (most children grow out of it at age 3 but the twins were a rare exception). French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin had recently moved from Paris to the University of California at San Diego for a faculty position when he first heard about the twins. He immediately decided that Gracie and Ginny would be ideal subject matter for his first solo directorial effort but the result entitled Poto and Cabengo (1979) could not really be classified as a documentary. Instead, it is a highly personal non-fiction portrait that is closer to an experimental film than anything else and Gorin’s involvement with the twins and their family become just one aspect of the movie’s multi-layered narrative interests.

The story of the twins and their family provide a fascinating backstory to Gorin’s work although it isn’t really covered in any detail in his movie. But here are the basic facts. Tom Kennedy from Georgia was stationed in Germany with the Air Force when he met Christine, a German woman, at a Munich dance festival. They later got married and moved to Columbus, Georgia, where they found work and Christine gave birth to twin girls in 1970. Unfortunately, the newborn babies suffered violent convulsions after their birth and a Georgia neurosurgeon told the parents that the twins might be mentally deficient although it might take five years to properly chart their development and confirm that diagnosis.

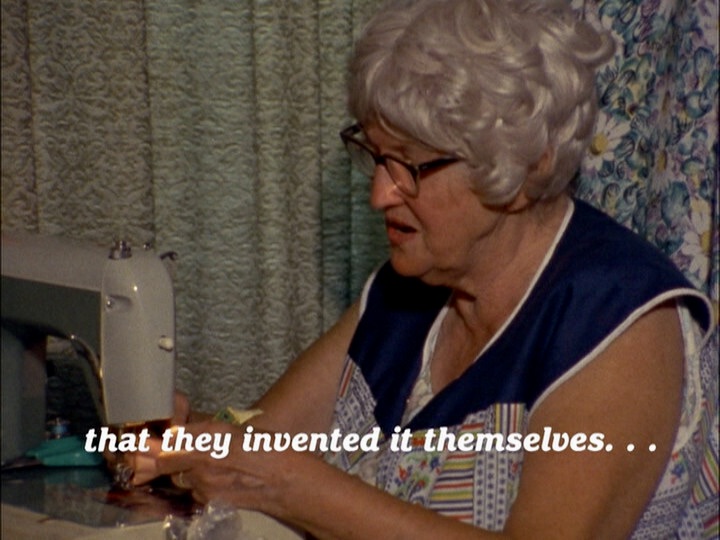

The Kennedy family soon experienced financial difficulties with Tom losing his job as an accountant so they decided to more to California for better job opportunities. The family ended up living in Linda Vista, a suburb of San Diego, and Christine’s mother came over from Germany to live with the family and take care of the children while the parents tried to find work. One problem was the fact that the grandmother only spoke German (she only knew a few words of English and didn’t bother to learn the language). The parents had also chosen not to send the twins to school and kept them mostly inside their home and away from interacting with children their own age or anyone outside the home (Was this a case of neglect or hapless ignorance?).

It was in this claustrophobic environment that Gracie and Ginny began to speak to each other in a language that was original and undecipherable but later turned out to be a mashup of English, German and gobbledygook. According to a Time magazine article from 1997, the writer observed that “They had an apparent vocabulary of hundreds of exotic words stuck together in Rube Goldberg sentence structures and salted with strange half-English and half-German phrases. The preposition out became an active verb: “I out the pudatoo-ta” (I throw out the potato salad). Potato could be said in 30 different ways.”

It wasn’t until 1977 that the twins finally started receiving help from the Children’s Hospital in San Diego. Their introduction into public life and interacting with other children helped improve their learning skills and motor functions like running, jumping or even drawing after several years in isolation. But could they ever catch up and live functional lives on their own after being shut out of the world during their formative years?

What is intriguing about Poto and Cabengo is Gorin’s lack of interest in deciphering the twins’ odd speech patterns as opposed to exploring the concept of language and the environment that produced this situation in the first place. In an interview with Bomb Magazine, he described the origins of his first feature: “I got hold of the event through the press…They built up a case which reeked of Wild Child mystique. The very day I saw the first article on the twins, Eckart Stein from ZDF [German Television] was passing through town and I sold him the idea of a film. I lied through my teeth, told him that I had seen the twins, seen the therapists who took care of them at Children’s Hospital, secured the rights to the story. I assured Stein that they spoke a “private language.” He agreed to do the film. But when I saw the twins for the first time I immediately realized that the story as the press—and by then, myself—had cast it was not there. There was no private language and never had been.”

As Gorin spent more time with the girls and her family, his film became more exploratory and complex, touching on other topics besides the phenomenon of idioglossia, such as the difficulties of raising children in impoverished circumstances, never mind the fact that the girls have special ed needs. The dynamic between the husband and wife is also an ongoing narrative thread as Tom struggles to find work as an independent real estate agent while his wife dreams of a better home and neighborhood for her family. Adding another layer of tension is the presence of the German speaking grandmother who, like the twins, doesn’t interact with anyone outside the home and can only communicate with her daughter.

There are moments of profound despair in Poto and Cabengo which can rival the existential angst on display in Salesman (1969), the acclaimed cinema-verite work by Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin. And there are scenes of deadpan absurdity as weird and comical as anything in Errol Morris’s Gates of Heaven (1978), a non-fiction portrait of a pet cemetery in California and the animal lovers who have buried deceased companions there. The thing that makes Gorin’s film so unlike a conventional documentary is his use of sound and image. Often a black scene is accompanied by the sound of the twins speaking to each other as a short text statement floats across the screen asking something like “What are they saying?” Chapter headings are sometimes whimsical or they can abruptly alter the flow of the narrative with a detour. The occasional use of music cues is also eclectic as noted by snatches of Erik Satire, “I Found a Million Dollar Baby” by Errol Garner and Mozart’s Fantasia in D Minor, K. 397 (performed by Glenn Gould),

Gorin also integrates 16mm home movie footage of the Kennedy household with newspaper headlines or TV news clips and there are interviews interspersed throughout the movie featuring sound bites of the speech therapists and linguistic experts commenting on Gracie and Ginny’s behavior and “twin speak.”

Among the more memorable moments is a sequence where Gorin takes the twins to the San Diego zoo and a library but their hyperactive nature and mercurial mood swings end up exhausting him in the end and he questions whether he has the patience and energy to deal with the children on his own. Also, the brief scenes of Gracie and Ginny speaking to each other in their unique way is enthralling because the girls clearly seem to understand each other but what we are hearing sounds like voices being sped up on a tape recorder and rendered as high pitched gibberish.

In his insightful notes on the DVD release from Eclipse (a spinoff of The Criterion Collection), Kent Jones comments on Gorin’s sound design, stating “its principal purpose is utilitarian: to steer the film up, down, and sideways, and finally guide us to the more unsettling seriocomic state of affairs deep within its material. The gap between Tom and Chris Kennedy’s vision of their economic situation and the gruesome reality is terrifyingly wide, a real-life version of early movie comedy’s fixation on the gulf between aspiration and achievement…This is not the comedy of cruelty but of extreme identification.”

True to form, Gorin doesn’t provide the kind of ending to Poto and Cabengo that gives closure to the story or to the viewer. When we last see the Kennedy family, life is not going well for them. The twins aren’t progressing as quickly as the speech therapists had hoped although they have mostly abandoned their private language. As a result, they ceased to be an item of interest to the media and were quickly forgotten. While their brief fame in the spotlight had some positive aspects – the family was able to move into a bigger house and a more desirable neighborhood thanks to seed money from TV and motion picture production companies who wanted to option the rights to their story – it ultimately became an ordeal when no movie offers came through and they had to sell their new home. Grace and Ginny were also split up and sent to different schools. We don’t really know what became of Grace and Ginny and their family after that as the movie ends there because Gorin has sated his interest on the subject and the end result is his solo directorial debut. Is he just as guilty as other reporters who were exploiting the twins for their own purposes as a unique human interest story? Or is he an empathetic and humane link between the Kennedy family and the outside world?

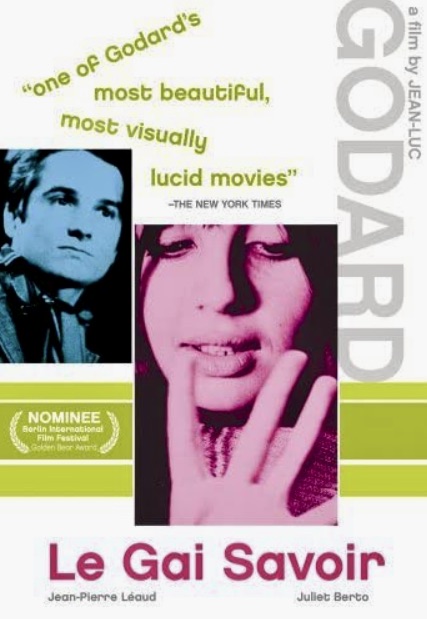

For those who are unfamiliar with Jean-Pierre Gorin, he was a radical leftist in Paris who befriended Jean-Luc Godard in 1966 and ended up collaborating with him on several films, first as an actor in Le Gai Savoir (1969) and then as an uncredited writer, editor and co-director on Godard films like Wind from the East (1970) and Vladimir and Rosa (1971), which were produced under the name Dziga Vertov Group. Their output was political in nature and heavily influenced by Bertolt Brecht’s “dialectical theater” and Marxist ideology. The 1971 film Tout va Bien starring Jane Fonda and Yves Montand was the only Godard film in which Gorin shared an on-screen credit as co-director and co-writer. In comparison to those decidedly uncommercial (and some would say unwatchable) projects, Poto and Cabengo is a remarkably different kind of cinematic experience and highly recommended for the adventurous cinephile. It also helps that Gorin was assisted by indie film legends Les Blank (Burden of Dreams, A Poem is a Naked Person) and Maureen Gorling (Blossoms of Fire, This Ain’t No Mouse Music) on his solo outing – Blank handled the cinematography and Gorling collaborated on the sound design and served as the film’s still photographer.

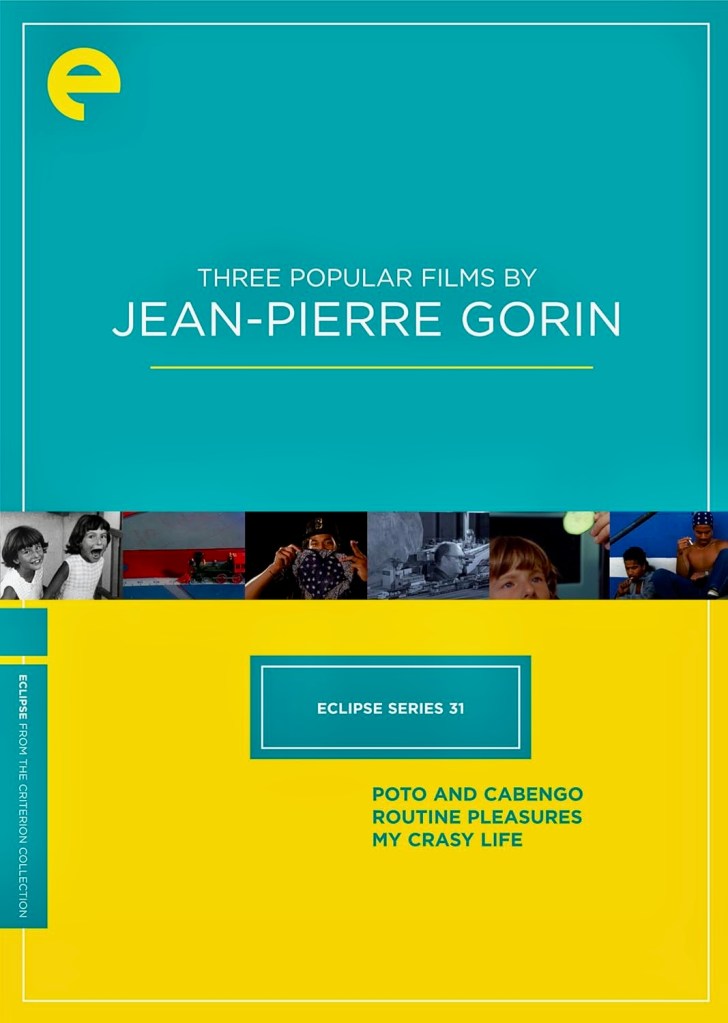

Poto and Cabengo was released on DVD in January 2012 as part of a 3-disc set by Eclipse/The Criterion Collection and includes the other two films in Gorin’s Southern California trilogy – Routine Pleasures (1986), in which the director finds connections between model train enthusiasts and film critic/painter Manny Farber, and My Crasy Life (1992), a portrait of a Samoan street gang in Long Beach, California.

Other links of interest:

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/1988/04/01/jeanne-pierre-gorin/

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2122-three-popular-films-by-jean-pierre-gorin