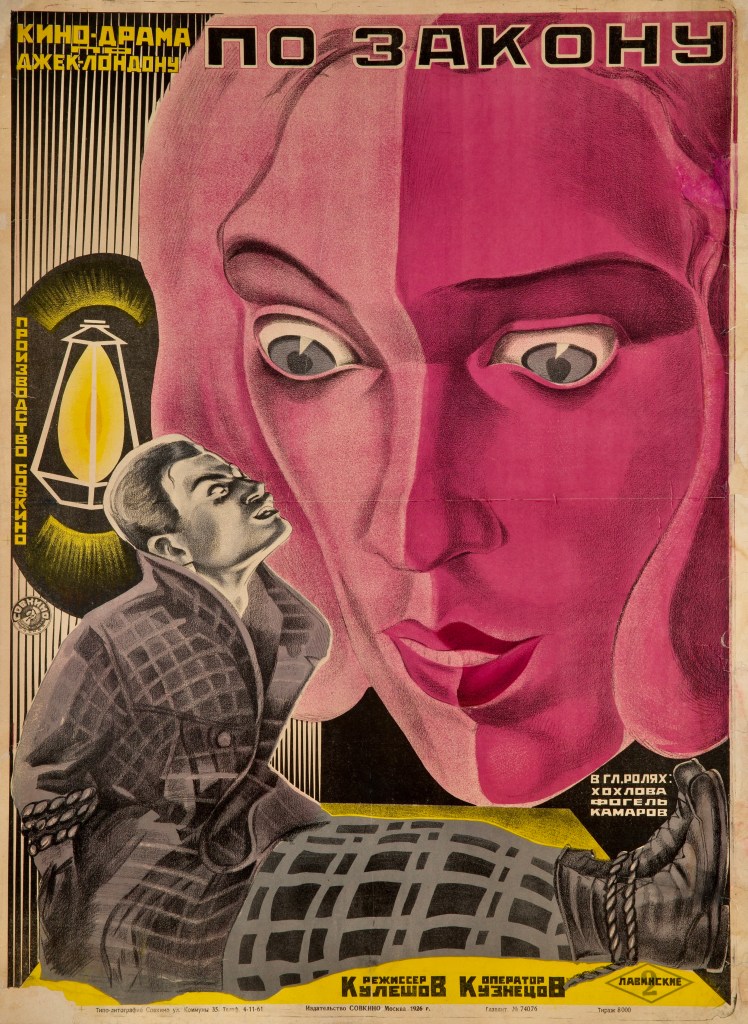

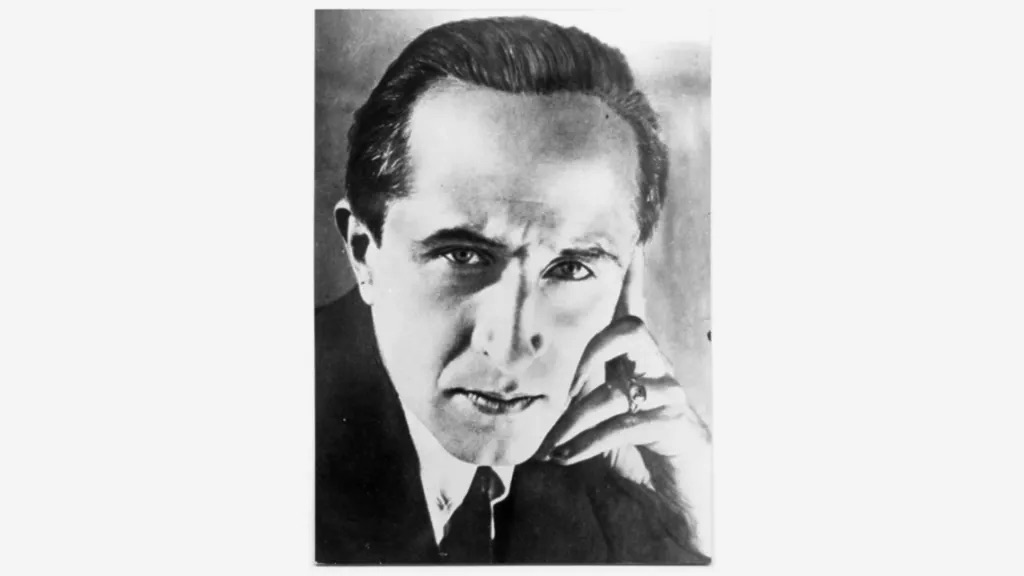

It is not a surprise that novelist/journalist Jack London was the most popular writer of the early 20th century and he enjoyed an international readership, especially in Japan, Eastern Europe and Russia. In fact, one of the landmark films of early Soviet cinema is By the Law (Russian title: Po Zakonu, 1926), based on London’s short story The Unexpected, and directed by Lev Kuleshov, a former painter turned set designer who eventually became a film theorist and director who launched the montage movement of the 1920s (Sergei Eisenstein [The Battleship Potemkin, 1925] was one of his students).

Filmed on an extremely low budget with a cast of five actors and a dog, By the Law opens in a remote area in the Yukon where a quintet of miners are about to give up hope in finding gold. Just as they are pulling up stakes to move to a new location, Michael (Vladimir Fogel), an Irishman, discovers gold on their claim and they spend the rest of the winter mining it. Unfortunately, there appears to a hierarchy in the group with Hans (Sergey Komarov), a Swede, and Edith (Aleksandra Khokholva), his British wife, the leaders of the group, Dutchy (Porfiri Podobed) and Harkey (Pyotr Galadzhev) occupy the middle tier and Michael is at the bottom of the social ladder and often treated like a servant.

Over time Michael’s grudge turns to hate and, one night when he is mocked at dinner by Dutchy and Harkey, he draws his gun and shoots them both in a spontaneous rage (It is interesting to note that the murders are not over the gold). Edith manages to get the gun away from him and Hans eventually beats Michael unconscious and ties him up. The trauma of the incident creates unbearable tension among the three survivors and a winter storm confines them to their cabin while Hans and Edith try to decide what to do with Michael – should they risk taking him to the authorities across an unforgiving landscape and weather or pass judgment on himself themselves?

The first option becomes impossible once flood waters surround the cabin and threaten to submerge the dwelling. Soon the claustrophobia of the situation leads Hans and Edith to become judge, jury, and executioner of their prisoner and By the Law moves to its grim conclusion which is clearly a critique of taking the law into your own hands. But wait….there’s an unexpected twist at the end that was not in London’s original story.

For a silent film from 1926 that runs barely eighty minutes, By the Law holds up remarkably well for a movie that is almost 100 years old. Part of this is due to its fast moving, economical structure, the kinetic editing, and Kuleshov’s inspired use of just a few locations – the camp by a river, the austere landscape and the rustic cabin, which becomes a prison of sorts for the three surviving miners.

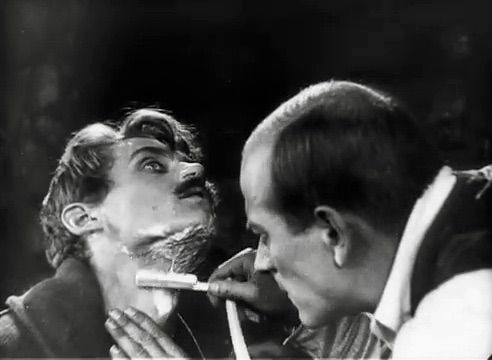

Kuleshov approached By the Law as an experiment and was able to raise funding for it because it had a small cast and just a few locations but the film is not just an exercise in shadow, light and potent visual compositions. It works as an intense human drama and Kuleshovs’ style of mixing extreme close-ups with body movements and the odd detail (a pot of soup boiling over, a pair of bound feet trying to wiggle out of the restraints, a stark tree designated for a hanging) makes the movie compelling on the level of a psychological thriller.

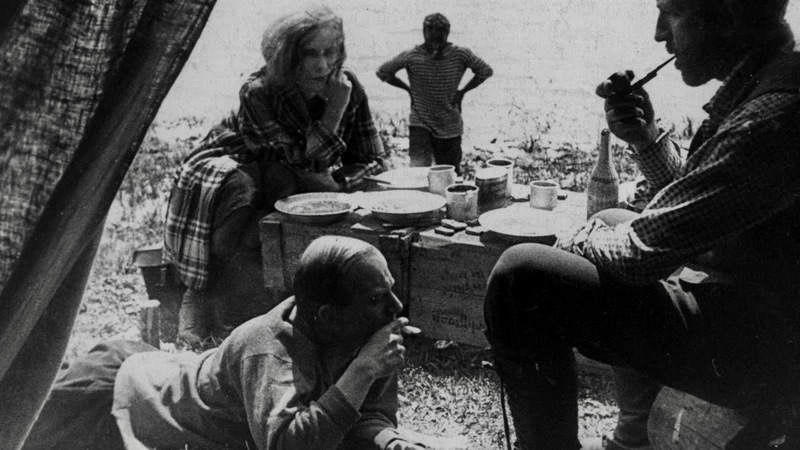

Certainly for a low budget project, Kuleshov faced various challenges during the shooting. “It is very interesting to remember how the outdoor shooting in By the Law took place,” he recalled in his journal. “We had to be in time to catch the ice flows thawing in the spring. We had a house built on the shore of the snowy river bank, and this house had to be flooded with water when the ice came into contact with it…First, it was necessary to work on the ice all the time. The actors’ hands and feet were scratched and bleeding.”

Watching By the Law you can almost feel the cold, the rain, the icy wind and the flood waters that swamp the cabin and you also get a very clear idea of the class envy and prejudices among the five miners that leads to the violence that erupts. Interestingly, Kuleshov felt strongly that editing was cinema, not acting, yet the three principal players are extraordinary in their roles, their flexible faces running through a range of extreme emotions, especially Aleksandra Khokhlova as Edith and her conflicted feelings over her implication in the tragedy.

Kuleshov’s films are rarely shown in repertory cinema anymore compared to his contemporaries like Sergei Eisenstein and Aleksandr Dovzhenko and film buffs are probably more familiar with “the Kuleshov Effect” than the director’s work. This technique, according to the website Editmentor.org, occurs when Kuleshov “edited three different series of shots using the same shot of a neutral faced actor combined with a different secondary shot within each series. In the first series there is a bowl of soup, the second a child in a coffin, and the third a reposed woman in a chaise. Later, he showed each series to a separate audience and asked the audience what they perceived in the actor’s performance. This resulted in three distinct interpretations from the audience. In the first series with the soup, the audience perceives the actor’s expression to convey hunger. When seeing the combination with the child in the coffin, they see sadness in his face. And when combined with the reclined woman, they interpret desire in his look. The actor’s shot is exactly the same in each series. However, the audience perceives a different emotion in his performance when combined with a different shot.”

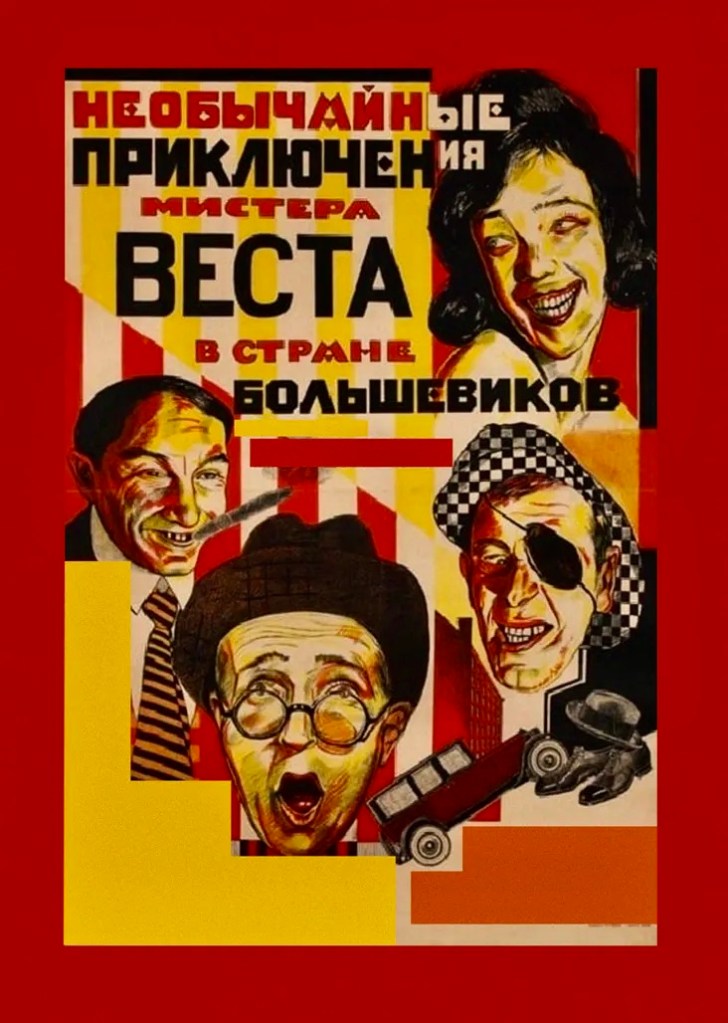

Prior to By the Law, Kuleshov made two highly influential and critically acclaimed films, The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924), a satire in the style of a chase comedy, and The Death Ray (1925), a lighthearted espionage tale with fascists battling socialists, both of which were more popular in the West than they were in Russia. In fact, Kuleshov’s work was heavily criticized in his own country. According of Juliet Jacques of Cineaste Magazine, “By the Law’s Western acclaim rested more in the film’s “Americanism” than its examination of the place of the individual within Soviet culture, which caused Kuleshov problems at home, particularly after Stalin’s insistence on cinematic Socialist Realism led to him being accused of “sins of formalism”…As it stood, no school was built on Kuleshov’s spare technique, and despite its influence on Carl Dreyer’s similarly claustrophobic masterpiece The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), By the Law represented not so much the beginning of a new type of silent film as its false dawn.”

You can stream By the Law on various platforms such as Youtube but probably the best presentation is on Flicker Alley’s DVD box set, Landmarks of Early Soviet Films, which also includes Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of Bolsheviks, Mikhail Kalatozov’s Salt for Svanetia (1930), and 5 other features. It is currently out of print but you can still find copies from internet sellers.

Other links of interest: