In May 1828 a young man appeared in a town square in Nuremberg, Germany carrying a prayer book and two letters written by his former caretaker. He spoke very little and was unable to answer any questions about his identity, where he came from or why he was there. One of the letters stated that he had come to the city to meet the captain of the 6th cavalry regiment with the hope of becoming a cavalryman. The other letter claimed he had been born in 1812 and had been raised in complete isolation from other people although he had been taught rudimentary reading and writing skills. His name was Kaspar Hauser but his mysterious nature and childlike presence baffled the townspeople and he was housed as a vagabond at the local prison until he was made a ward of the city and put under the protective care of Lord Stanhope, a wealthy aristocrat. Stanhope devoted himself to Hauser’s further education and re-entry into society and the young man’s bizarre demeanor aroused the curiosity of the public as well as doctors, professors and members of the clergy. Unfortunately, Hauser’s life came to an abrupt end in April 1833 when the mysterious man who first brought him to Nuremberg returned and stabbed him to death, escaping without a trace. The case has been a source of fascination for years in Germany and numerous films, television series and made-for-TV movies have been made about him but The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser aka The Mystery of Kaspar Hauser aka Every Man for Himself and God Against All (German title: Jeder fur Sich und Gott Gegen Alle, 1974), directed by Werner Herzog, is probably the most famous and critically acclaimed of all the versions made to date.

The true identity of Kaspar Hauser has never been solved. Some believe he was the heir of a grand duke or nobleman. Others thought he was an imposter who wanted attention and hoped to benefit from his charade. And there were doctors who felt he was mentally disabled or some kind of idiot savant. Herzog seems less interested in trying to unravel all of the theories about Hauser’s identity than in contemplating how the young man experienced the world. In other words, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is not a traditional biopic. The timeline between events in Hauser’s life is never clear, characters who meet and interact with him are introduced without backstories and crucial details from his biography are occasionally left out or occur offscreen.

Instead, Herzog serves up a poetic meditation on how the world might look to someone raised in a cell for most of his adult life with no human contact (other than his caretaker) and no knowledge of the outside world. Ordinary people don’t interest the director and Hauser is typical of Herzog’s fascination with protagonists who are extreme nonconformists, often without realizing it. “In all my films,” he said in an interview with Peter DeBruge of Variety, “there’s a sense of curiosity and always a sense of profound awe…to go to the outer limits of what we are, and looking deep into the very recesses of our soul.”

The first half of The Enigma of Kasper Hauser follows the man’s transition from living like an animal and crawling around the floor of his cell to slowly learning how to walk upright. His vocabulary expands and his writing and drawing skills improve. His refusal to eat anything except bread and water eventually gives way to a more discriminating palette and the ability to use eating utensils. A music tutor even teaches him how to play a Mozart composition on the piano but his curious view of the world makes him the sort of outsider that most people consider a freak. At one point in the film, he even winds up briefly in a traveling carnival’s human oddities exhibit, assuming the same stunned expression and rigid posture he first displayed after being abandoned in a town square in Nuremberg.

Although The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is a period drama which utilizes musical selections from Johann Pachelbel (“Canon in D major”), Tomaso Albinoni (“Adagio in G Minor”), Mozart (the opera “Die Zauberflote”), and Orlando di Lasso (“Requiem a 5”) to emphasize the title character’s immersion in high society culture, the movie also has a dreamlike feel to it with some scenes depicting Hauser’s ecstatic visions (a religious pilgrimage up the side of a fog covered mountainside, a blind man leading a caravan across the desert) and others displaying Herzog’s preference for the odd detail (a crane gobbling up a lizard, an autopsy of Hauser’s brain after his murder).

Herzog eloquently captures Hauser’s wonder but also incomprehension of the world around him in numerous scenes that are both touching and weirdly off kilter such as his amazement at the prison tower that stands before him. He tells Lord Stanhope (Michael Kroecher) he wants to meet the “tall man” who built such a monumental structure. In another scene, he is presented with a flickering candle and tries to grab the flame with his fingers as if he can hold it. His childlike responses can sometimes end in pain for himself or social awkwardness and confusion for others. Yet there is a guilelessness and purity about Hauser that make the people he encounters in society seem like some alien species that are studying him like a laboratory rat when they are the ones out of sync with nature.

Some critics of the film complained that Herzog and his co-scenarist Jakob Wassermann constructed certain sequences to illustrate how society deadens and corrupts natural human behavior and that Hauser is an idealized version of a noble savage. This may be true to some degree but it doesn’t detract from the movie due to the mesmerizing presence of Bruno Schleinstein, billed as Bruno S., in the title role.

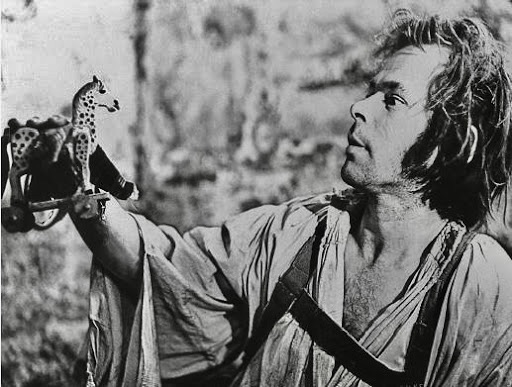

For a director who has always been fascinated with eccentric characters who live outside the realm of normal society, Bruno S. is the ultimate interloper. Diagnosed as a schizophrenic, Bruno S. spent most of his youth in mental institutions. Herzog first discovered him through the 1970 German documentary, Bruno der Schwarze – Es blies ein Jager wohl in sein Horn. As an adult, Bruno S. supported himself as a forklift operator at a car factory. As a self-taught musician, he also enjoyed playing the piano, accordion, glockenspiel and other instruments at garden parties. Bruno S. so completely embodies the role that one forgets they are watching a performance and are seeing a documentary about the real Kaspar Hauser instead.

In her mixed review of The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, The New Yorker critic Pauline Kael admitted that Bruno S. was “amazing” in the role, adding, “His Kaspar has sly, piggy eyes, yet he’s so totally absorbed in experiencing nature, his head thrust out ecstatically, straining to grasp everything he was denied in his cave existence, that he becomes Promethean; the light dawning in that face makes him look like a peasant Beethoven.”

Working with such an eccentric personality and untrained actor like Bruno S. certainly presented Herzog with daily challenges during the making of the film but he earned his lead’s trust from the beginning (or there would have been no movie). In Paul Cronin’s interview book, Herzog on Herzog, the director recalled, “Sometimes he was very unruly and would rant about the injustices of the world. All I could do when this happened was to stop everyone and allow him to say whatever he wanted to say. I got quite angry with a sound man who, after an hour of this ranting, opened a magazine and started to read. I said to him, ‘You are being paid now to listen to Bruno. All of us will listen to him.’ After a few minutes of this Bruno would see that everyone was looking at him, and would say, ‘Der Bruno [he often spoke of himself in third person] has talked too much. Let’s do some good work now.’ I constantly said to him, ‘Bruno, when you need to talk and speak about yourself, do it. It is not an interruption for us. It is very much a part of what we are doing here. Not everything needs to be recorded on film.”

Herzog would go on to use Bruno S. again in his 1977 film Stroszek in which he played an alcoholic drifter who immigrates to America with a prostitute and an elderly man. The trio end up living in a mobile home in a dreary rural area in Wisconsin in one of the strangest road movies of all time. In his review of the film, Roger Ebert wrote, “The thing about most American movies is that the actors in them look like the kinds of people who might be hired for a movie…Herzog often frees himself of this restraint by using non-actors…And Bruno S. is phenomenon. Herzog says that sometimes, to get in the mood for scene, Bruno would scream for an hour or two. In his acting he always seems to be totally present: There is nothing held back, no part of his mind elsewhere. He projects a kind of sincerity that is almost disturbing, and you realize that there is no corner anywhere within Bruno for a lie to take hold.”

Unfortunately, the relationship between Herzog and Bruno S. later became estranged with Bruno accusing the director of exploiting him as a person. Herzog denied this and said, after Bruno died of heart failure at age 78 in 2010, that he was the best actor he ever encountered: “There is no one who comes close to him…I mean in his humanity, and the depth of his performance, there is no one like him.” (from an interview with Brad Avery for Boston Hassle).

Among the many narrative fictions that Herzog has created on film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser remains one of his greatest achievements along with Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982). In recent years most moviegoers are more familiar with Herzog’s work as a documentarian thanks to the international acclaim he has received for such unforgettable portraits as My Best Fiend (1999) about his love/hate relationship with actor Klaus Kinski, Grizzly Man (2005), Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) and Into the Inferno (2016). As much as I admire his work in the documentary field, however, I would love to see him return to narrative features and subject matter as haunting and thought-provoking as The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser.

Herzog was not the only one fascinated by Kaspar Hauser as evidenced by the many film and TV adaptations of the story, most of them made in Germany. IMDB lists a 1915 silent film version (does it really exist?). There was a 1965 TV movie, a 1966 mini-series entitled Der Fall Kaspar Hauser and a 1969 TV movie featuring the contributions of 10 directors including Wim Wenders. In addition, there was the 1993 film Kaspar Hauser, directed by Peter Sehr, an Italian film entitled The Legend of Kaspar Hauser (2012) with Vincent Gallo in the title role and an animated short called Kaspar (2012) from Canada.

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser has been released on VHS and DVD by different distributors over the years but Herzog fans should check out Shout Factory’s Herzog: The Collection, which was released in a dual format presentation (Blu-ray & DVD) in 2014 and includes 15 of the director’s most iconic works from the 70s and 80s such as Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), Fata Morgana (1971), Woyzeck (1979) and The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser.

Other links of interest:

https://allthatsinteresting.com/kaspar-hauser