Nothing Sacred (1937) is a key film in that short-lived genre known as ‘the screwball comedy,” a unique Hollywood creation that flourished between 1933 and 1940. Distinguished by its eccentric characters, irreverent humor, and breakneck pacing, these films usually featured privileged but irresponsible characters running amok against the backdrop of the Great Depression when society was in turmoil. But while the idle rich were mercilessly lampooned in the most popular screwball comedy of the previous year – My Man Godfrey (1936) – the whole human race gets dished in Nothing Sacred, from the newspaper industry to a public that enjoys reading sob stories about someone else’s misfortune.

This means that the film isn’t afraid to offend viewers with sequences that could be deemed racist, sexist, misanthropic or mean-spirited but you could also say that some of the most famous comedians in the world have probably been guilty of all those things in their comedy routines at one time or another. Because of this, Nothing Sacred has been downgraded from its classic status by some critics in recent years such as Roger Moore who wrote on his Movie Nation blog: “Accept a movie as representative of its time, appreciate how times have changed and take all that into account when you watch it. Let your jaw drop at the “I cannot believe they WENT there…in 1937!” But there’s no getting around the story elements that make “Nothing Sacred” problematic, that take you out of the picture and won’t let it age well. Some of the comedy is so seriously “not funny any more” that the luster is fading on this “classic” too fast for the shine to last.” Make of that what you will, Nothing Sacred is still rather remarkable for its no-holds-barred satire but also stands as a supreme example of William Wellman’s versatility as a director, regardless of the genre. He was a master class in filmmaking, whether it was a war picture (Wings, 1927), crime drama (The Public Enemy, 1931), Pre-Code melodrama (Heroes for Sale, 1933), action adventure (Beau Geste, 1939) or western (The Ox-Bow Incident, 1942) and that’s just citing a few.

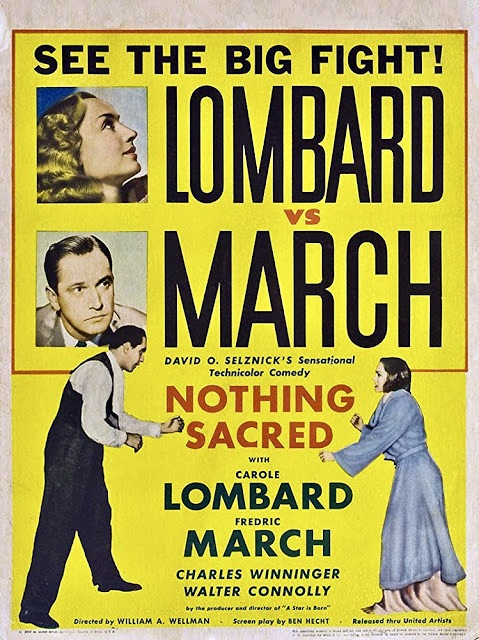

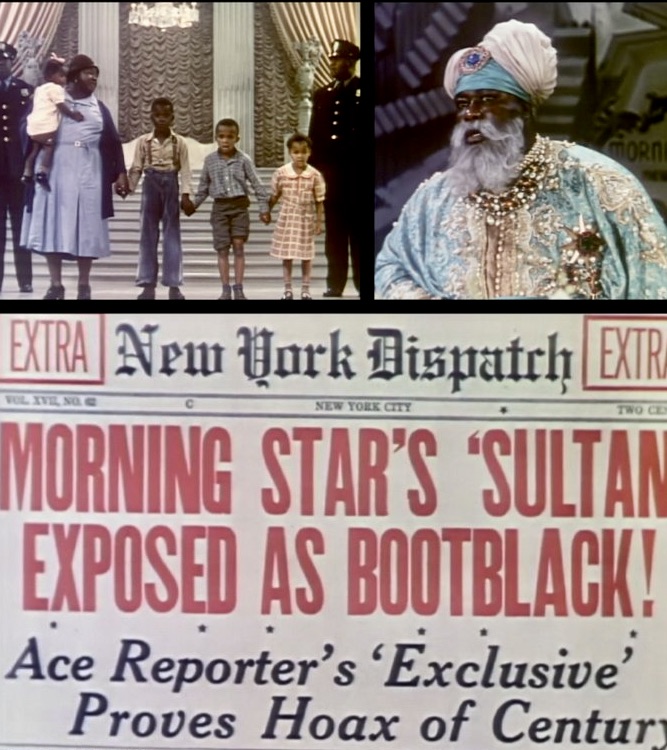

Here is the basic synopsis: When Wally Cook (Fredric March), an ambitious newspaper reporter for The New York Morning Star, tries to pass off a penniless Harlem resident as the “Sultan of Mazipan” at a charity event, his hoax is discovered and Cook’s editor demotes the reporter to writing obituaries as punishment. In his new position, Cook learns about a young woman in Warsaw, Vermont named Hazel Flagg (Carole Lombard) who has just learned from her doctor that she has a short time to live due to radium poisoning. Sensing a great news story, Cook rushes to interview the patient, only to learn the diagnosis was incorrect and the woman is in perfect health. Undeterred, Cook convinces Flagg to pretend the original diagnosis was correct, resulting in a series of tearjerking news stories, national headlines and a wave of public sympathy for the young woman. But how long can their charade last before the truth is revealed?

Ben Hecht, a former Chicago newspaper man working as a Hollywood screenwriter, was hired by producer David O. Selznick to come up with a comedy for Carole Lombard in the spring of 1937. After several false starts, Hecht finally heeded Selznick’s suggestion to adapt the short story, “Letter to the Editor” by James H. Street, that had appeared in Hearst’s International-Cosmopolitan. Hecht’s screenplay was titled Nothing Sacred and included a part for his friend, John Barrymore.

Unfortunately, Selznick incurred Hecht’s anger when he refused to use Barrymore who, at this point in his career, had become an incurable alcoholic. The final straw for Hecht was when Selznick demanded a ‘happy ending’ for what was clearly intended to be a very black comedy and the writer walked off the production. The screenplay was then handed over to Dorothy Parker and Robert Carson to polish the dialogue and eventually Ring Lardner, Jr. and Budd Schulberg were brought in to provide an acceptable ending.

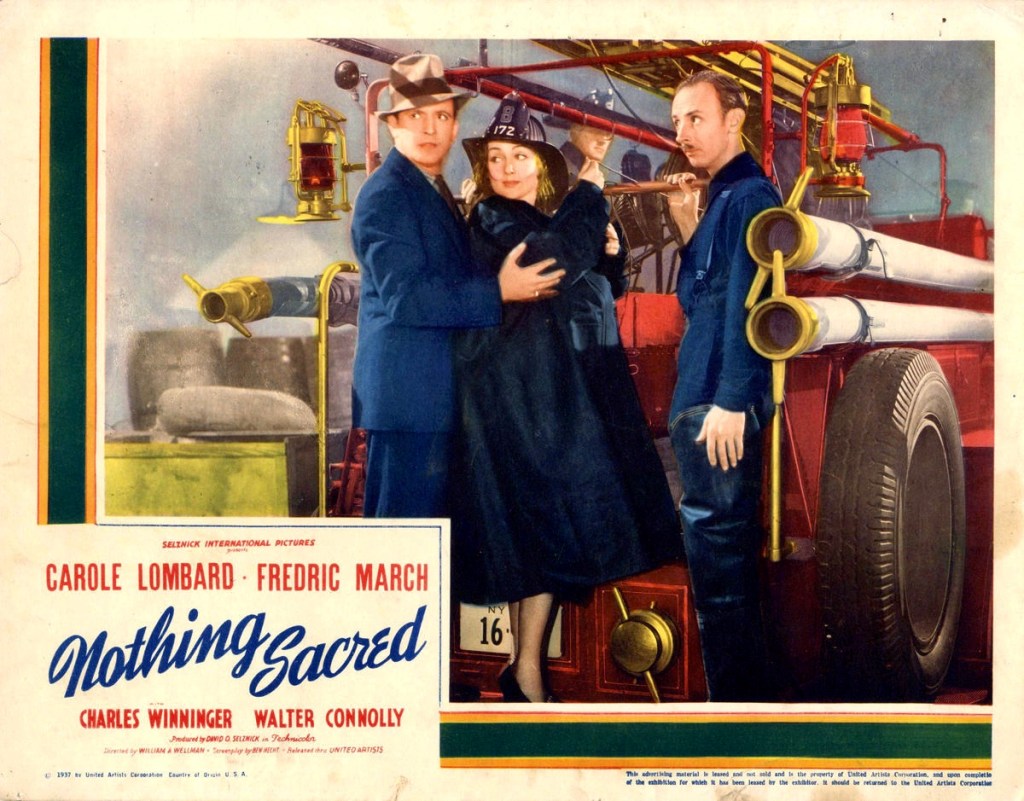

Despite the bad blood between Hecht and Selznick, the actual filming of Nothing Sacred was a high-spirited affair that often resembled a non-stop party. Practical jokes were the order of the day and, at one point, Lombard had director William Wellman bound in a straitjacket by some strong-armed crew members so she could have his undivided attention. Wellman, in turn, showed Lombard how to tackle a man in preparation for her free-for-all with Fredric March at the film’s climax.

Lombard’s zany sense of fun even affected the usually humorless March who went careening around the Selznick lot with her in a rented fire engine during a production break. It was generally known in Hollywood circles that Lombard wasn’t particularly fond of March ever since he tried to seduce her on the set of The Eagle and the Hawk (1933) but the two actors got along famously on this picture.

Carole Lombard often said Nothing Sacred was one of her favorite films and it’s certainly an ideal showcase for the dazzling blonde comedienne who deservedly became the “Queen of Screwball Comedy” after her performances in this, Twentieth Century (1934), and My Man Godfrey (1936).

Besides Lombard’s performance, Wellman’s expert direction, and the sharp dialogue, Nothing Sacred also deserves a footnote in film history as the first use in a color film of process effects, montage and rear screen projection. Backgrounds for the rear projection were filmed on the streets of New York and Paramount would later refine this method in their subsequent color features.

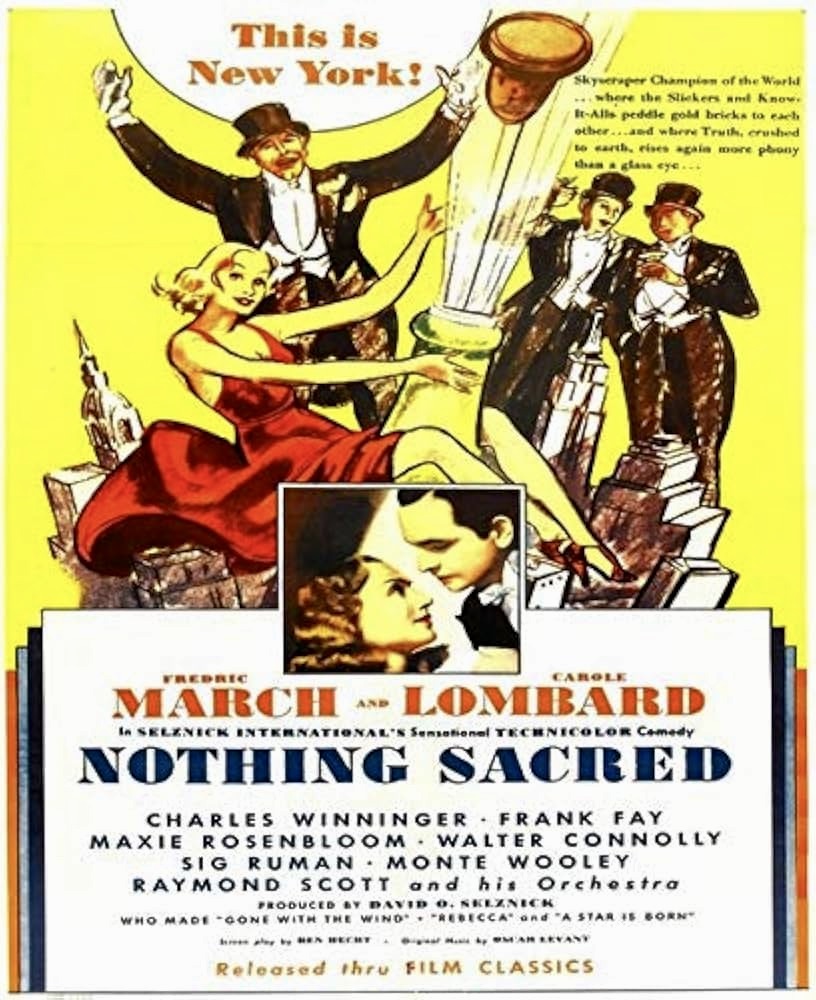

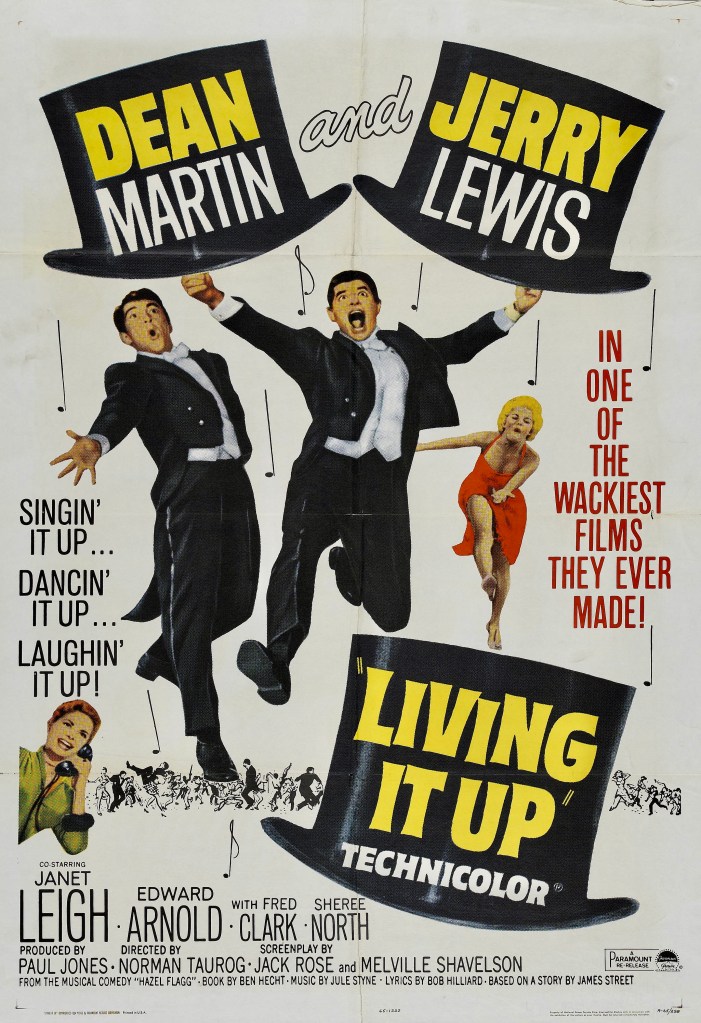

Nothing Sacred would later serve as the basis for the Broadway musical, Hazel Flagg, which premiered in 1953. Then Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin starred in a 1954 remake entitled Living It Up with Lewis in the Lombard role, Dean Martin as the doctor, and Janet Leigh as the reporter.

At the time of its release, Nothing Sacred received mostly rave reviews. The New York Times called it “one of the most entertaining shows of the season,” and Variety stated “Hecht handles the material breezily and pungently, poking fun in typical manner of half-scorn at the newspaper publisher, his reporter, doctors, the newspaper business, phonies, suckers, and whatnot…the running time is only 75 minutes, making this a meaty and well-edited piece of entertainment from start to finish. There are no lagging moments.”

Surprisingly, the film was not a financial success despite good notices. Nor did Nothing Sacred garner any Oscar nominations. Wellman had just come off of A Star is Born (1937) when he directed this so maybe the critical and popular success of the former movie overshadowed Nothing Sacred. On the positive side, he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Director for A Star is Born and picked up an Oscar (which he shared with Robert Carson) for Best Original Story for the same film.

In recent years, Nothing Sacred is still considered a high water mark in the screwball comedy genre by numerous high profile film critics like David Thomson who wrote, “Nothing Sacred is such a relief in its assumption that movies might just as well be quick, throwaway, cynical, and funny as monuments to something or other. I don’t mean to say Nothing Sacred is perfect – it’s not as searching or as magical as Godfrey or Bringing Up Baby. But it’s a true reflection of the “cockeyed” wisdom – that the world was a ridiculous place and it would be a good thing if a few smart young people saw that and said so in a way that makes you laugh. If you want to get the best, bravest insouciance in Hollywood of the thirties, you’re better off going to comedies like this than the sagas.”

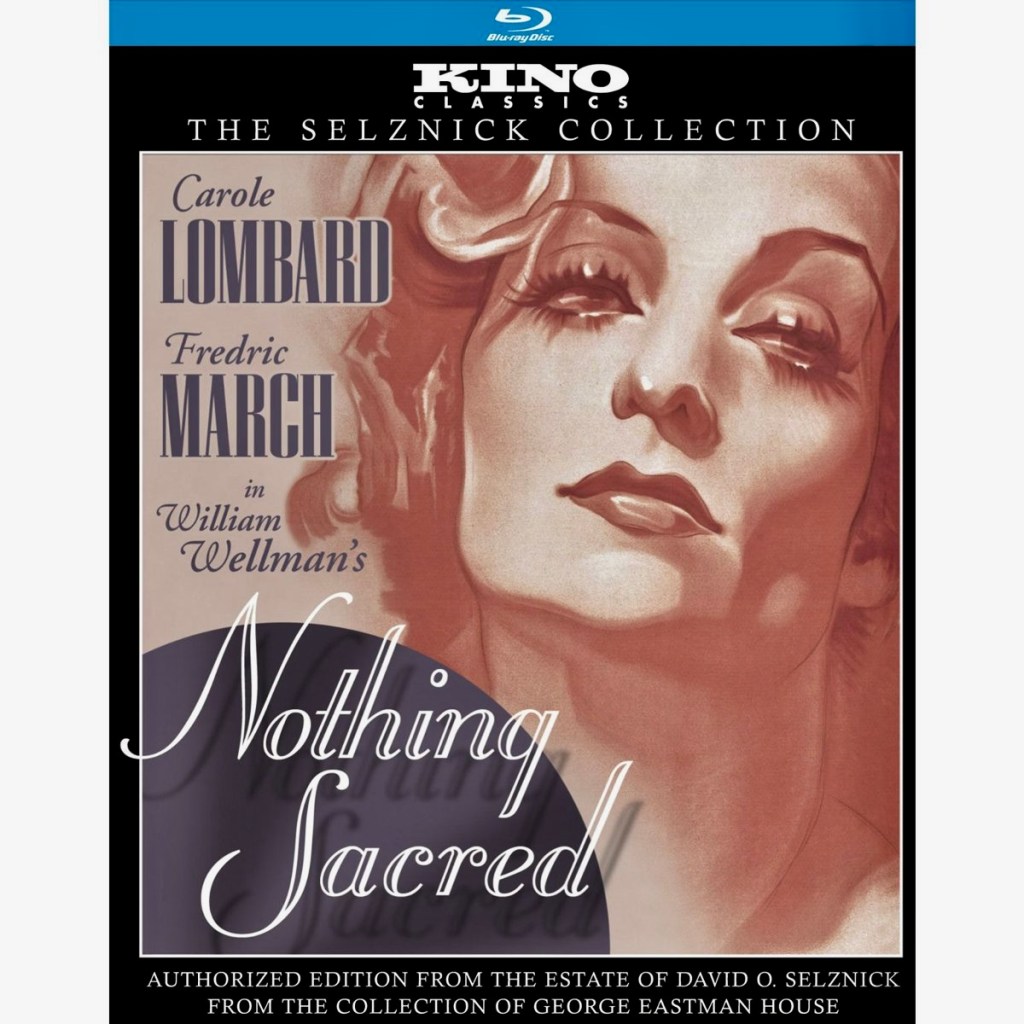

Nothing Sacred has been released on various formats over the years but for fans of the movie the Blu-ray edition released by Kino Lorber in December 2011 is probably the one collectors will want to own.

*This is a revised and expanded version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

Others links of interest:

https://cinecollage.net/screwball-comedy.html

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/cad-of-the-century-two-new-biographies-of-ben-hecht/

http://www.silentera.com/people/directors/Wellman-William.A.html