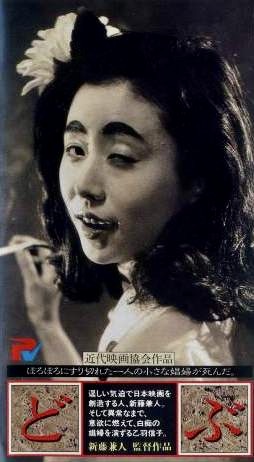

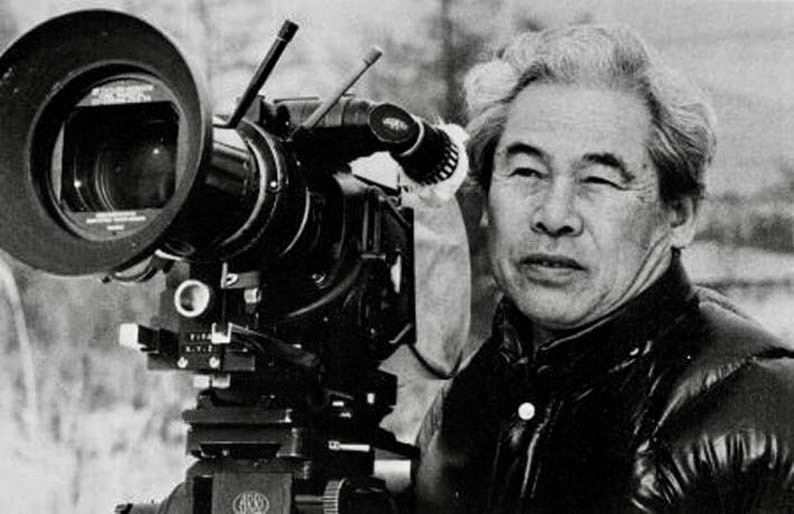

One of the most famous Japanese directors of his generation (1912-2012) to emerge from the post-WW2 years was Kaneto Shindo but, outside of a handful of films, most of his work remains largely unseen in the U.S. That is a shame because much of his filmography provides a fascinating glimpse into the lives and mindsets of Japanese people, especially the working class, in the difficult years following the country’s defeat in the war. One of his earliest and most provocative depictions is Dobu (1954), which is also known as The Ditch, but is more accurately translated as The Gutter. And the main protagonist of the film is Tsuru (Nobuko Otowa), who could easily claim to be the most memorable guttersnipe of all time. When the film opens, she is a filthy, wandering beggar on the verge of starvation who collapses in a shantytown known as Kappunuma and here she will remain for the rest of her brief life.

Dobu is an immersion into the lower depths of Japanese society in the post-war years and the people portrayed in the film have reached rock bottom, desperately trying to survive as best they can. Among the down and out residents are Toku and Pin, two unemployed factory workers who are roommates and spend most of their idle time gambling what little money they have at the horse races. They end up taking the homeless Tsuru into their home but the decision is not a matter of compassion. They see Tsuru as someone they can exploit for their own purposes and soon they manage to sell her off as a hostess to a saloon where the local slumlord and other moneyed clients are pampered with booze and available women.

That arrangement turns out to be a total disaster for everyone involved. For one thing, Tsuru is not quite right in the head. We never learn whether her seemingly simpleminded behavior is the result of a brain injury from bombings during the war or whether it is from being beaten in a riot at the factory where she once worked. It could also be that she has suffered a complete mental breakdown after a lifetime of abuse and she shares her tale of woe with Toku, Pin and their shantytown neighbors in a flashback sequence which reveals some of the vile men who have crossed her path and mistreated her.

Despite the poverty-stricken setting and the frantic circumstances of the Kappunuma community, Dobu is not the slog through miserabilism that you might expect from the above description. Some of the film is surprisingly comic while other aspects of it provide a fascinating critique of the local government and authority figures such as Shihazo, a developer who plants to evict all of the slum dwellers and build a sports arena on the marshlike land.

Tsuru, in particular, serves as an unlikely heroine because she can often seem like a half-wit with her socially awkward behavior and a stupefied, open-mouth expression that encourages people to call her an idiot. At the same time, she has an innate understanding of injustice, not just for herself but for her oppressed neighbors, and she is not afraid to stand up to bullies or defend herself from attacks. Still, there is something ambivalent about the way director Shindo presents Tsuru as pathetic and laughable in one scene and then rebellious or surprisingly resourceful in another.

In one of the more comical episodes, she dresses up like a geisha girl, dons a wig and tries her best to play the role of an attractive bar hostess but hasn’t the faintest idea of how to pull that off. When a potential client asks her what skills are her speciality, she replies that the only thing she knows how to do is stand on her head! In this respect, Tsuru can sometimes seem as childlike and naïve as the waiflike heroine of Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957). But when you see the abuse Tsuru suffers at the hands of men and some women, you realize that any possibility of future happiness is probably not in the cards for her.

[Spoiler alert] Dobu builds to a tragic climax in which Tsuru is shot by a policeman who misinterprets her behavior as a psychotic freakout with a gun. In actuality, she is only trying to defend herself from a group of prostitutes who attack her for wandering onto their turf. After her death, the residents of Kappunuma mourn her demise and feel guilt for the way they treated her. (This final section of Dobu seems reminiscent of the wake in Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (1952), which may have been an influence on Shindo). It’s too little, too late, of course, but it is also revealed that Tsuru was suffering from a fatal disease and so her death was a mercy killing after all.

Nobuko Otowa, who plays the ill-fated Tsuru, was married to Kaneto Shindo. She was his third wife and they made numerous films together, starting with Shindo’s debut feature, Aisa Monogatari (English title: Story of a Beloved Wife, 1951), which was a fictionalized account of the director’s first wife and her death. Otowa is so convincing in her performance as Tsuru in Dobu that, if you weren’t familiar with the actress, you might think Shindo had hired a disheveled street person to play the role. Otowa would go on to win numerous acting awards at Japanese film festivals for her work with Shindo and, in 1979, she was awarded the Best Actress prize at the Venice Film Festival for Kosatsu, a controversial drama about a shocking family tragedy.

As Shindo’s sixth feature film, Dobu was certainly a controversial film for Japanese audiences due to the film’s portrait of people living on the fringes of society and the choice of a protagonist who was bound to be polarizing to viewers. His decision to build his narrative around a feral, half crazed woman and her experiences was a radical departure from most character studies in Japanese cinema and some film historians and movie critics didn’t feel the concept worked.

In her survey of Japanese cinema, The Waves at Genji’s Door: Japan Through its Cinema, Joan Mellen wrote that with Tsuru’s death, “Gutter passes into extreme sentimentality as Shindo exhorts the exploiters of people like Tsuru to appreciate the goodness of Japan’s working class…The ultimate message of what Shindo may have thought was a politically daring film can be only that political action on the part of those like Tsuru and her friends (and, by indirection, the audience) is not required. Once those most cruel see what harm they are doing, they will of their own volition cease and desist from tormenting the weak.”

Even though Shindo was still finding his way as a director when he made Dobu, the film is much more accomplished and complex than Mellen’s dismissal of it as a failed political critique. If nothing else, the movie presents a fringe/outsider culture most Japanese viewers would prefer to ignore since it points out the shameful failures of the country’s post-war initiatives. Dobu is also certainly more realistic in its portrayal of slum dwellers than Akira Kurosawa’s Dodes’Ka-den (1970), which dwelt with a similar group of displaced people living in a Tokyo garbage dump but was more theatrical and whimsical in its presentation.

By the time, Shindo made Dobu he had already established himself as a director on the rise with his third feature, Children of Hiroshima (1952), the story of a teacher who returns to her hometown four years after the war to pay her respects to her deceased parents and sister and to hear stories from the survivors. For someone who was born in Hiroshima, the events of August 6, 1945, when the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on the city, is something that profoundly affected Shindo and his work for the rest of his life. And references to the Hiroshima bombing would continue to resurface throughout his filmography: Lucky Dragon No 5 (1959) focuses on a crew of tuna fishermen who were exposed to the lethal effects of nuclear testing in 1954 at Bikini Atoll; Mother (1963) was a character study of an A-bomb survivor; Lost Sex (1966) features a male protagonist who becomes impotent through radiation sickness; and Sakura-tai Chiru (1988) is a semi-documentary about a left-wing theatre group who were wiped out by the Hiroshima bombing.

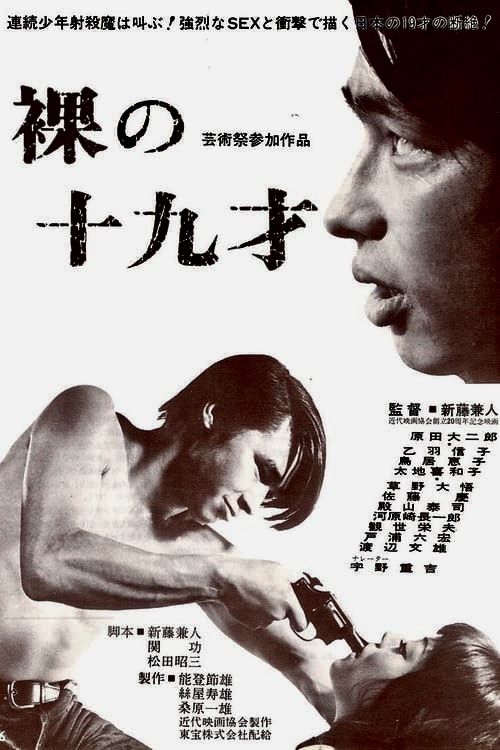

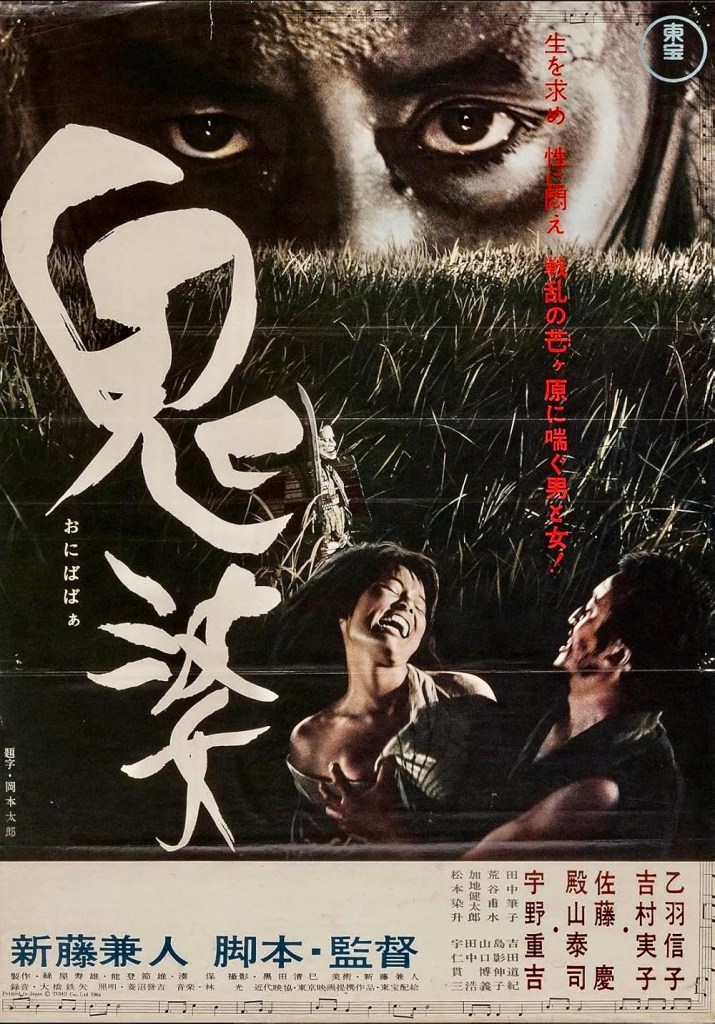

None of those films received theatrical releases in the U.S. and are virtually unknown here but Shindo is internationally famous for three key films in his career, two of which are often classified as horror/supernatural thrillers – Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968), and The Island (1960), a minimalistic, documentary-like portrait of a family of four struggling to exist on an arid patch of land in the sea. All three of those are essential viewing but it would be wonderful to see a revival of interest in Shindo’s career that would allow admirers of his work to finally see earlier efforts like Dobu and later films like Live Today, Die Tomorrow (1970), based on the real life case of a 19 year old homicidal sociopath named Norio Nagayama.

Dobu is not currently available on any format for purchase in the U.S. but you can stream an acceptable copy of it at the Cave of Forgotten Films website.

Other links of interest:

https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/where-begin-kaneto-shindo

https://www.kqed.org/arts/105125/kaneto_shindo_life_during_and_after_wartime

https://www.godzillacineaste.net/people/otowa-nobuko