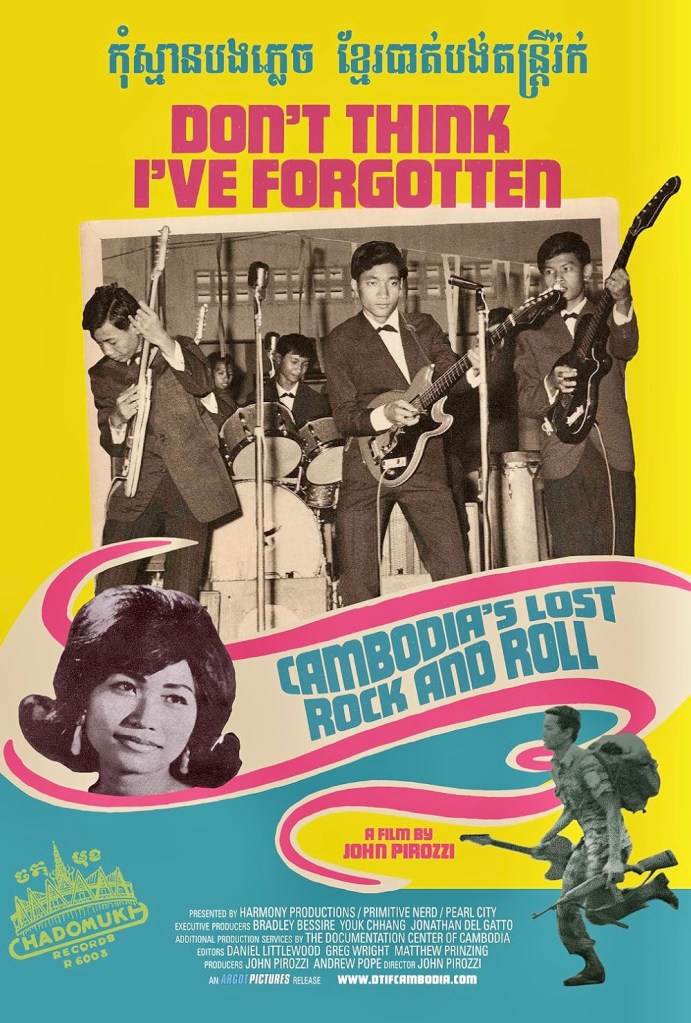

Most musicologists and historians of popular culture generally agree that rock and roll is an American creation but, as a lifetime music lover, I particularly love hearing and seeing how that pop culture movement influenced other societies around the globe. You don’t think of a country like Cambodia as a fertile breeding ground for innovative rock and roll but it was – in the late fifties through the mid-seventies – until the Khmer Rouge took control of the country in 1975. At that point rock and roll (and all music and culture considered “foreign” or western to the communist regime) was outlawed and any evidence of it (albums, tapes, etc.) destroyed, effectively erasing almost twenty years of pop culture…or so, they thought. John Pirozzi, director of Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll (2014), discovered enough missing pieces of that forgotten music scene to put together a fascinating and deeply moving portrait of a particular place and time that should appeal to rock and rollers everywhere.

Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll might not break any new ground in the documentary format with its chronological approach and mixture of talking heads, film clips, photographs and archival footage but the subject is so rich and mostly unknown to western viewers that it stands out as a unique window into an exotic subculture. Besides getting a crash course in the history of Cambodia in the 20th century, Pirozzi’s documentary also introduces you to the haunting voices and irresistible music grooves of bands from Phnom Penh, the capitol of Cambodia, that became the rock and roll hub.

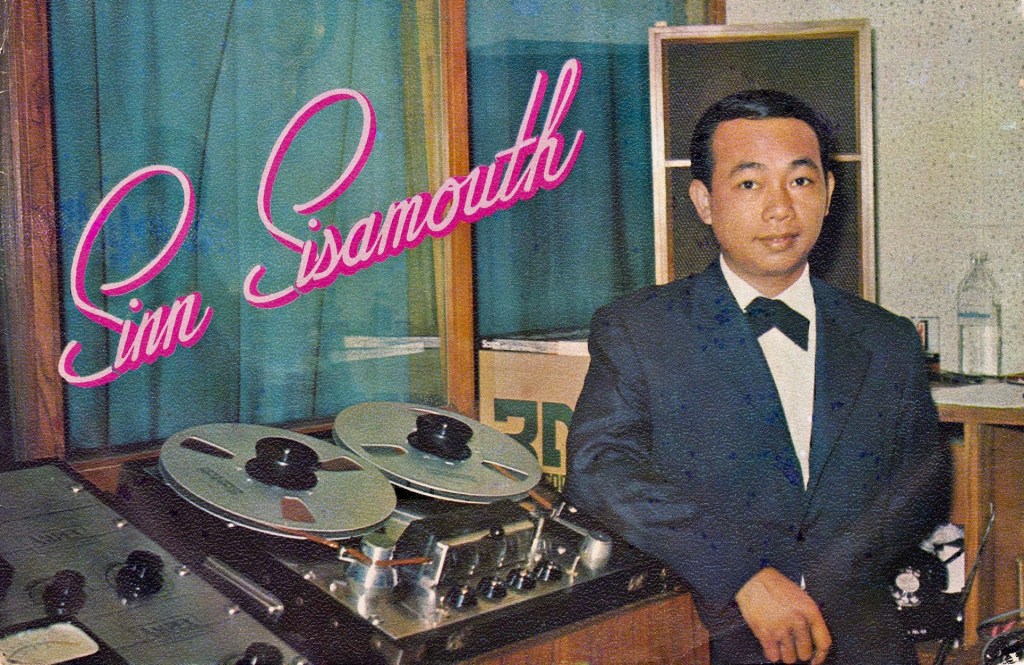

One of the most influential figures in Cambodian pop music was Sinn Sisamouth, whose relentless curiosity about all kinds of music, especially new forms, helped usher in the rise of rock and roll. At first, he and other Cambodians, who had been under French rule until 1953 when the country gained its independence, were fond of chansonniers like Charles Trenet, Tino Rossi and Edith Piaf. Then, Johnny Hallyday, often called “the French Elvis Presley,” came along in the late fifties and his single “Souvenirs” introduced Sisamouth and other musicians to a new emerging sound. Cliff Richard and the electric guitar sounds of his backup group, The Shadows, were another major influence.

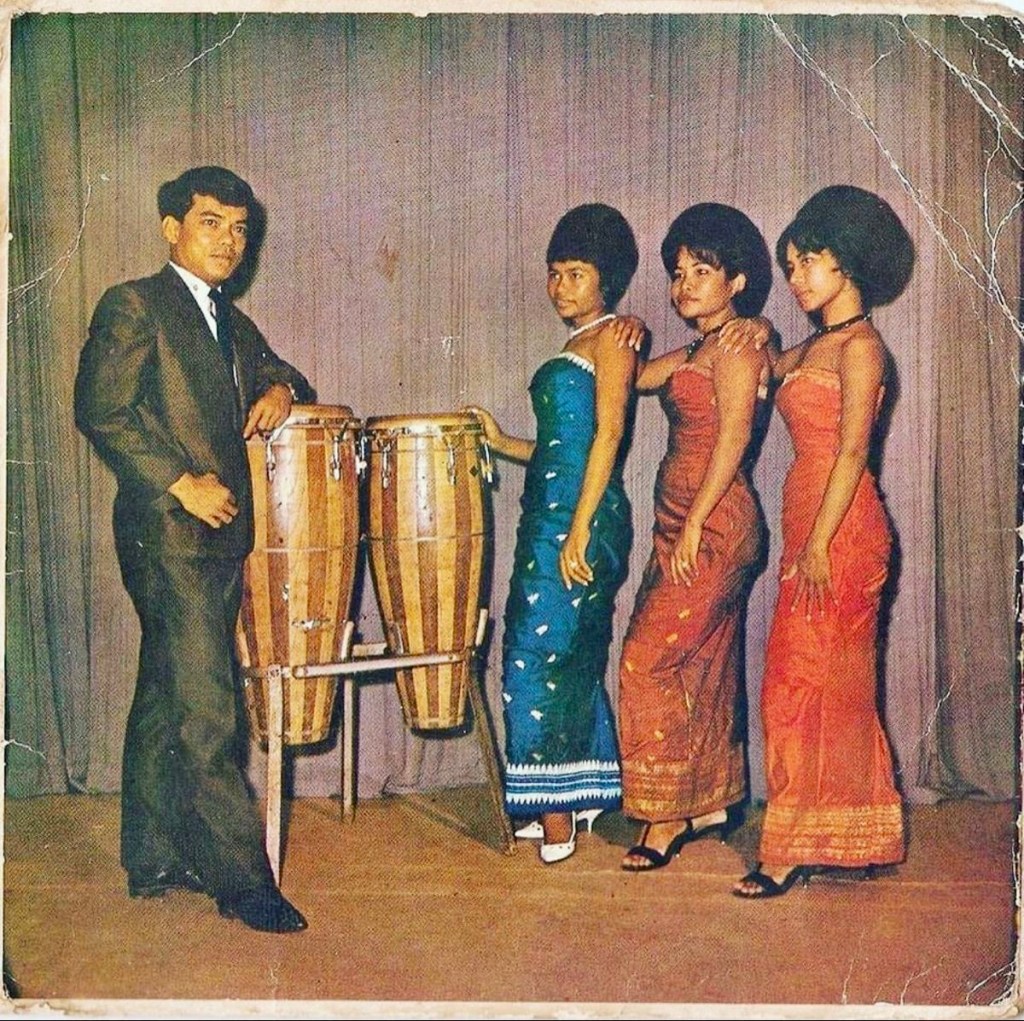

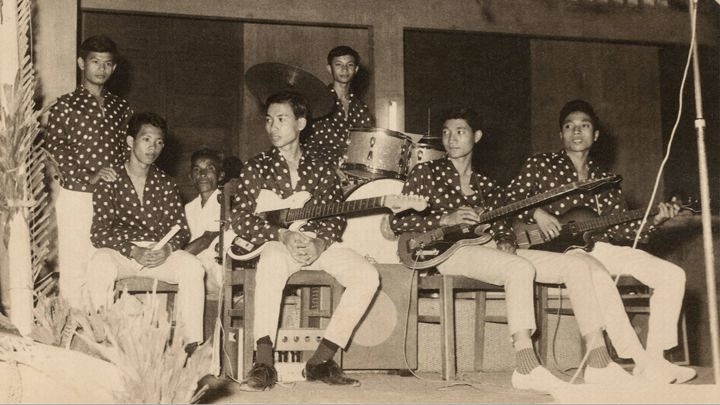

Almost overnight a younger generation of musicians were creating their own version of rock and rock/pop music, combined with percussion elements from Afro-Cuban rhumbas and soukous. Once American troops arrived in 1965 (as the war in nearby Vietnam began to heat up), music from the U.S. began to infiltrate the local radio stations bringing Motown, psychedelic rock from the West Coast and other pop music to Cambodian youth. Santana, in particular, made a big impact in 1970 and Sisamouth and his younger contemporaries took these influences and made their own sounds with them.

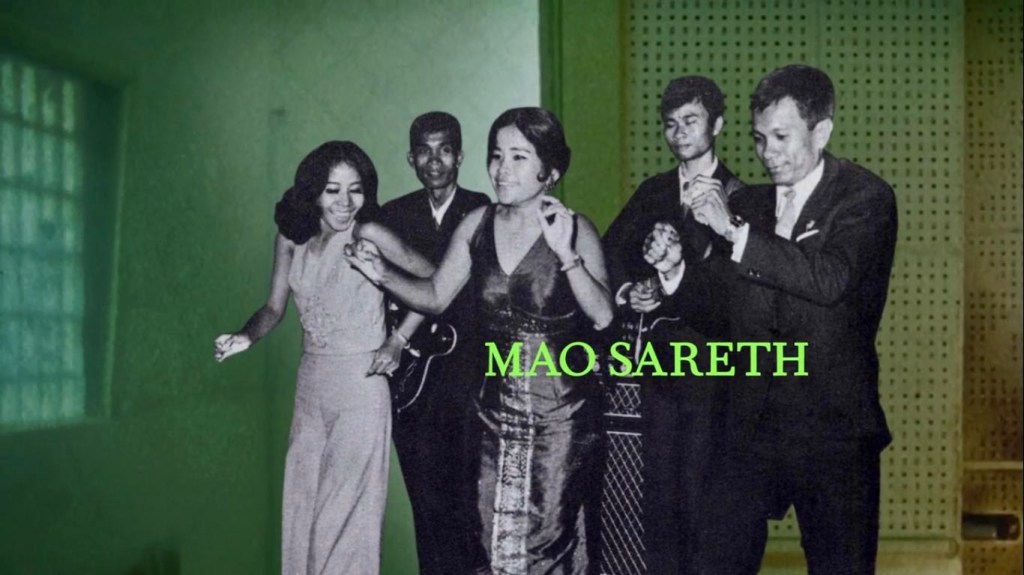

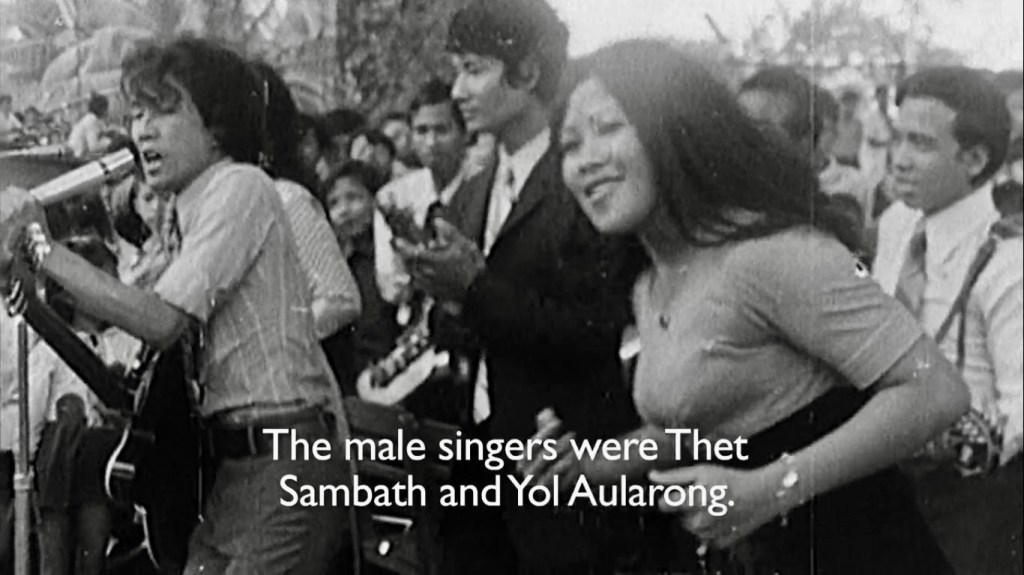

In addition to Sisamouth, the other major music figures introduced in Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll include female singers Ros Serey Sothea, Pen Ran and Huoy Meas, the rock groups Baksey Cham Krong and Drakkar, and the rebellious, pre-punk singer Yol Aularong. Even though there is precious little footage of these entertainers in action, you do get to hear various samples of their hit songs such as Sothea’s killer “Don’t Be Angry” or a mixed language version of Carole King’s “You’ve Got a Friend” by Pou Vannary.

It is an intoxicating mix of sounds that will probably make you want to hear more. What is shocking to learn is that most of these musicians were imprisoned by the Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot’s leadership and sent to work in the labor camps, where many died or disappeared. Anyone caught singing rock and roll or a foreign song could be executed on the spot. In fact, anyone identified as a musician, journalist, educator, artist or even wearing long hair could be targeted for death. As one survivor says in the film, “If you want to eliminate values from past societies, you have to eliminate the artists” and Pirozzi’s film is a tribute to those magnificent voices and talents who were silenced by their oppressors.

The Khmer Rouge’s four-year reign over Cambodia had a devastating effect, resulting in the deaths of more than 2.2 million people. Pol Pot and his followers were finally forced to flee to western Cambodia in 1978 when a massive army of soldiers from the Socialist Republic of Vietnam invaded the city of Kampuchea, the former headquarters of Pol Pot, and soon Vietnamese forces reclaimed the city of Phnom Penh.

Luckily, a handful of musicians from Cambodia’s rock and roll heyday survived to share their memories of that terrible time such as singer Sieng Vanthy, who identified herself as a banana street vendor when interrogated by the Khmer Rouge, or Chhoun Malay, a huge fan of Hank Williams who eventually immigrated to the U.S. and settled in Alabama.

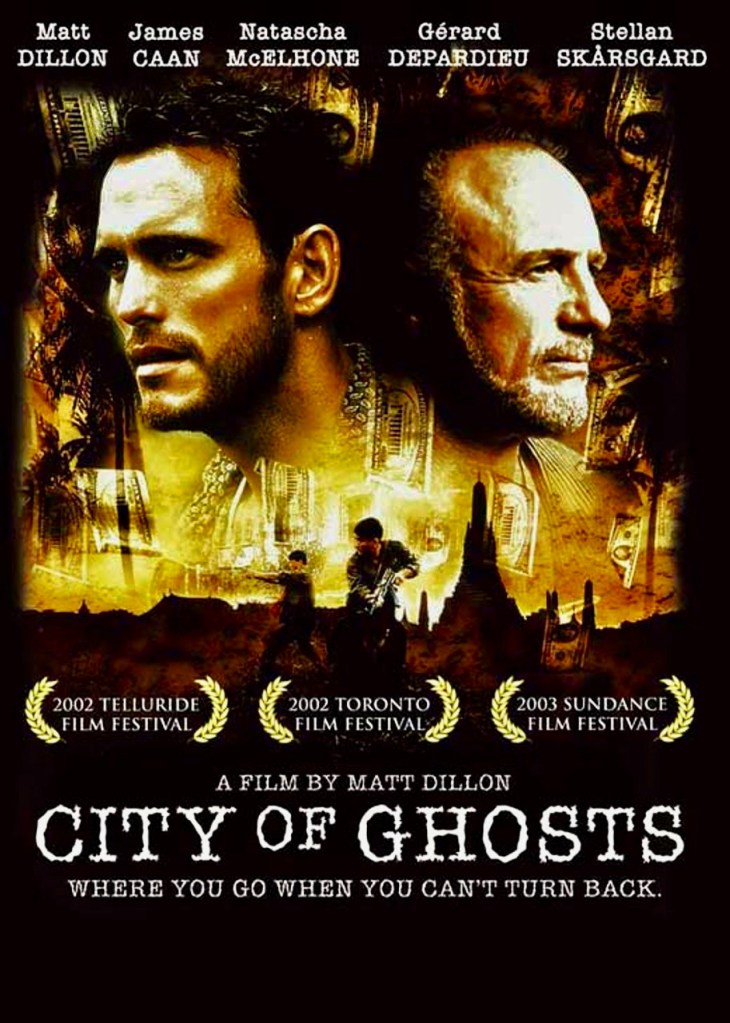

Although Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll is the second documentary feature from director John Pirozzi (his previous one was 2007’s Sleepwalking Through the Mekong on the Cambodian influenced rock group Dengue Fever), he is better known as a key grip, gaffer and camera operator on a variety of projects that encompass feature films (Juice, Bad Lieutenant), TV series (The Looming Tower, The Deuce) and filmed concerts (Leonard Cohen: I’m Your Man, Patti Smith: Dream of Life). He admitted in an interview with Lauren Oyler for Vice that he first learned about the sixties rock and roll scene in Cambodia when he traveled to the country in 2002 to work on Matt Dillon’s directorial debut City of Ghosts.

“I certainly knew who the Khmer Rouge were, but I didn’t know the particulars of how they came to power and what exactly had happened,” he said. “You could see that the city was very different from what it had been.” At first, he wanted to do a documentary on what happened to Cambodia during the seventies but then decided to just focus on the musical scene. “I wanted to show that this music would endure beyond everything it had been put through….The music is the one thing that has allowed the Cambodian people to access a time when their life wasn’t about war and genocide.”

Of course, the challenge of making a film like Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll was the scarcity of archival material available but once Pirozzi announced his intentions to the media, Cambodian survivors from the Pol Pot era began to contact him with invaluable material, everything from long lost record albums to faded photographs. As Pirozzi stated in an interview with NPR, “People held onto it, people hid it, people saved it,” he says. “There’s so many people who came to me when they found out about the film who had little pieces to the puzzle — who had songs, who had photos, who had maybe a little bit of footage. And so the film sort of came together in a very communal way, with people who really cared about the music and cared about the country.”

Although Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten was an independent documentary with limited distribution outlets, it garnered a number of high profile reviews such as A.O. Scott of The New York Times, who wrote, “Mr. Pirozzi’s film is an unsparing and meticulous reckoning of the effects of tyranny on ordinary Cambodians. It is also a rich and defiant effort at recovery, showing that even the most murderous totalitarianism cannot fully erase the human drive for pleasure and self-expression.” Steve Smith of The Boston Globe also praised the film, writing, “Although there is genuine horror in the way that many of these luminaries were cast into shadow, prematurely and brutally, there remains a certain triumph to be had in Pirozzi’s film.”

You might be able to still purchase a DVD of Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock ‘n’ Roll from online sellers or stream it on Amazon or Kanopy. The soundtrack CD is also still available from Dust to Digital, the label that released it at https://dust-digital.com/collections/cd. And if you want to see a completely different documentary approach to the Khmer Rouge occupation of Cambodia, check out Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture (2013), which is illustrated by clay figures and miniature dioramas.

Other links of interest:

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2015/05/15/john-pirozzi/

https://www.npr.org/2015/04/22/401020275/the-nearly-lost-story-of-cambodian-rock-n-roll

https://www.notablebiographies.com/Pe-Pu/Pol-Pot.html

Covering some of the same ground is Rocking Cambodia: Rise of a Pop Diva. It’s a documentary about a modern Cambodian rock band but goes back over the same history. (Link goes to the BBC Storyville which is no longer available unfortunately).