There is one cinema gimmick that always works for me and can sometimes lift a movie out of the ordinary and take it somewhere unexpected. This usually occurs when someone either puts on a mask or appears in one. The simple act of doing this immediately brings something theatrical and visually arresting to the scene that taps into our subconscious on an almost primeval level.

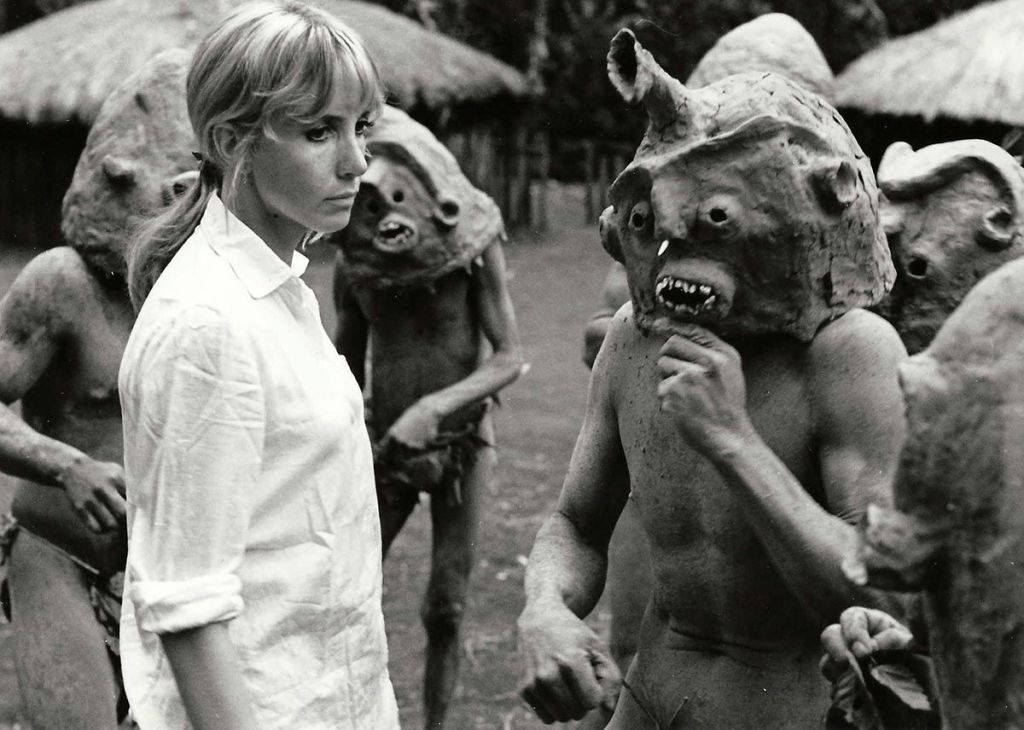

As Gerald Casale of the band Devo says in one of the featurettes on the Criterion Collection edition of Island of Lost Souls (1932), “Masks are one of the most primitive expressions of either trying to frighten other people or trying to create an alternate reality or trying to represent a deity or whatever. Ritualistically, masks have a lot of power.” Certainly the half-animal, half-human faces of the creatures who populate Island of Lost Souls are masks of a kind, the results of a highly skilled make-up artist (Wally Westmore) who transformed actors into a nightmarish new species.

According to The Columbia Encyclopedia, masks “are used by primitive peoples chiefly to impersonate supernatural beings or animals in religious and magical ceremonies.”

Masks are also utilized by cults such as satanists or groups practicing pagan rituals as in the islanders depicted in The Wicker Man (1973).

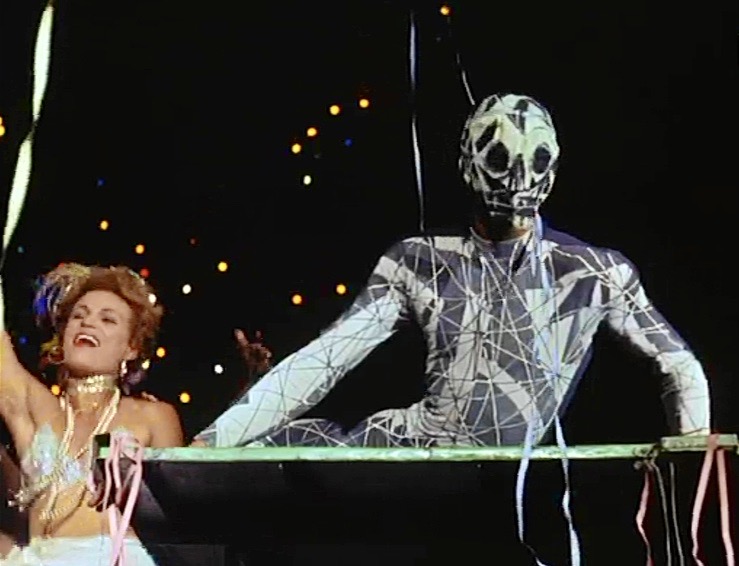

But when it comes to the use of real masks in films, there is always a transformative power involved for both the wearer and the viewer. I am particularly intrigued by films in which the wearer develops an alter ego when masked. For anyone who has ever enjoyed the ritual of Halloween, this is undeniably appealing. People react to you in different ways, especially if they can’t guess your identity, and as a result, you feel free to be the sort of person or thing they are responding to. Putting on a mask sets the stage for a performance of sorts.

Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” – Oscar Wilde

By no means a comprehensive pictorial history of masks in the movies, this blog is simply an excuse to showcase some of my favorite examples of the subject’s rich possibilities.

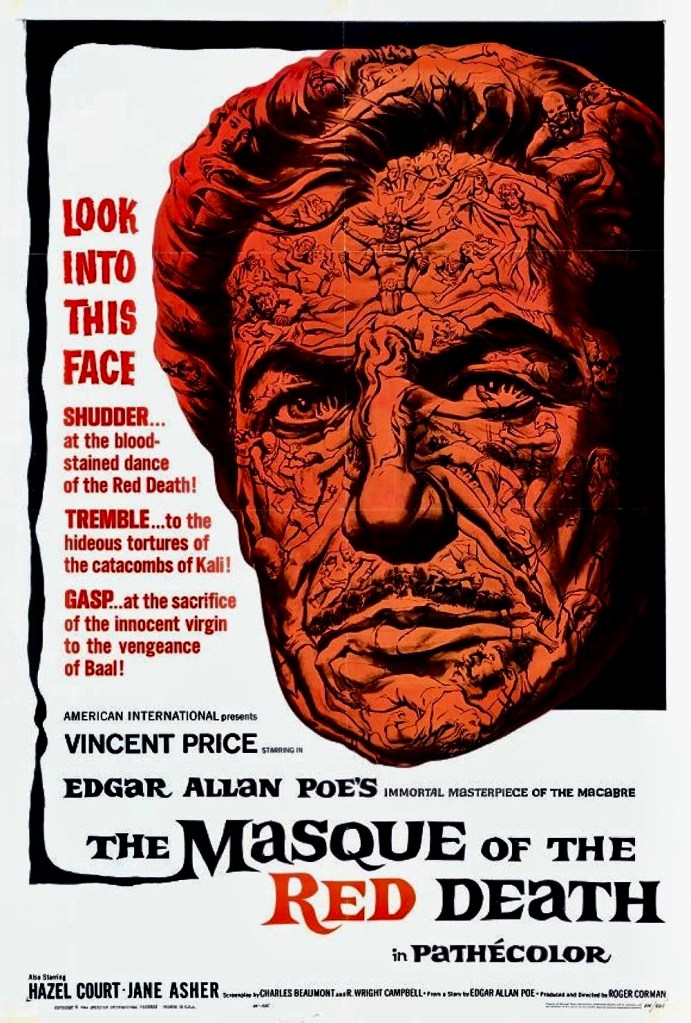

Is my costume such a disguise that you don’t recognize me?” – Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

Many iconic screen heroes have wore masks from the silent era on with Zorro, Scaramouche, the Lone Ranger, and Batman – in their many incarnations – just a few of the more obvious examples.

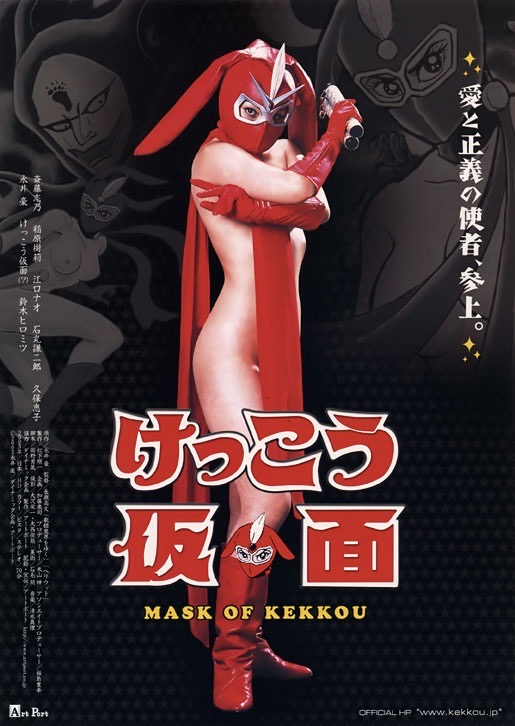

It is some of the lesser known or more fringe characters though that hold an even more exotic appeal such as the female crusader of Kekkou Mask (1991) and its sequels; naked except for a cape and a mask, she rescues abused Japanese schoolgirls from a sadistic principal.

Equally outrageous and similar in concept is Legendary Panty Mask (1991) in which the heroine, wearing a disguise made out of leather underwear, comes to the rescue of schoolgirls being violated by nuns in the western town of Tombstone. Another go-for-broke outrage from Japan.

Well known to French cinephiles but not as familiar to American moviegoers are the many shape-shifting appearances of the phantom-like Judex in Georges Franju’s 1963 remake of the popular 1916 French serial from director Louis Feuillade. It was part of a grand tradition that included Feuillade’s earlier serial thriller, Fantomas (1913).

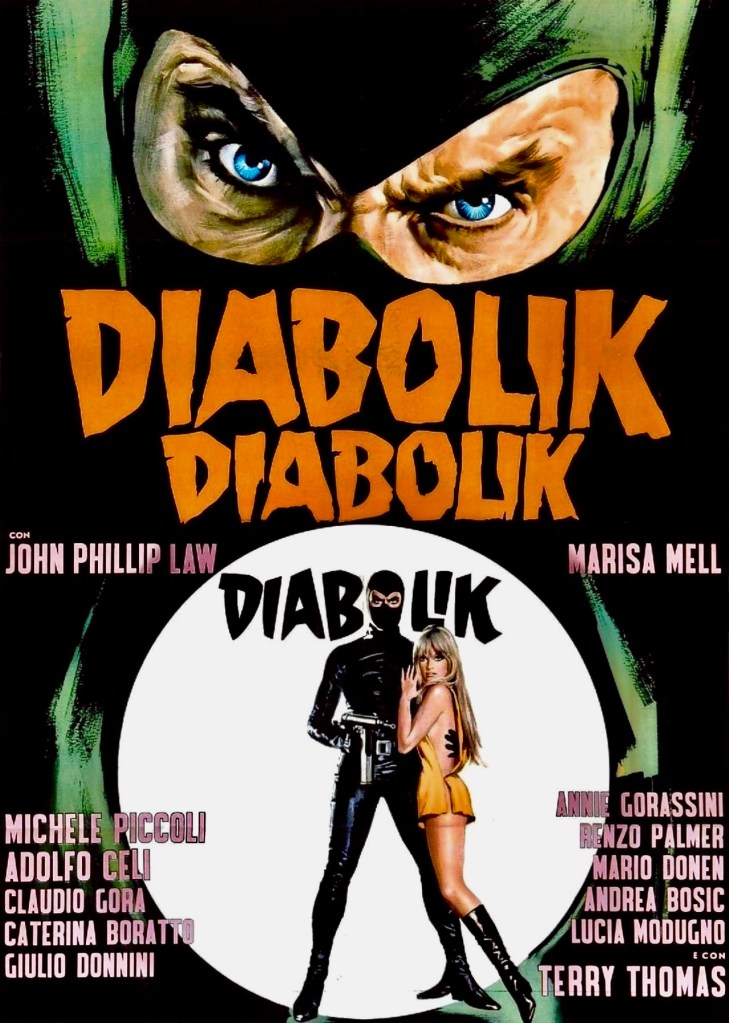

John Phillip Law plays a Fantomas-like super criminal in Mario Bava’s Danger Diabolik (1968).

Irma Vep (1996) is Oliver Assayas’s homage to the cinema of Feuillade and Les Vampires (1915) starring Maggie Cheung in the title role.

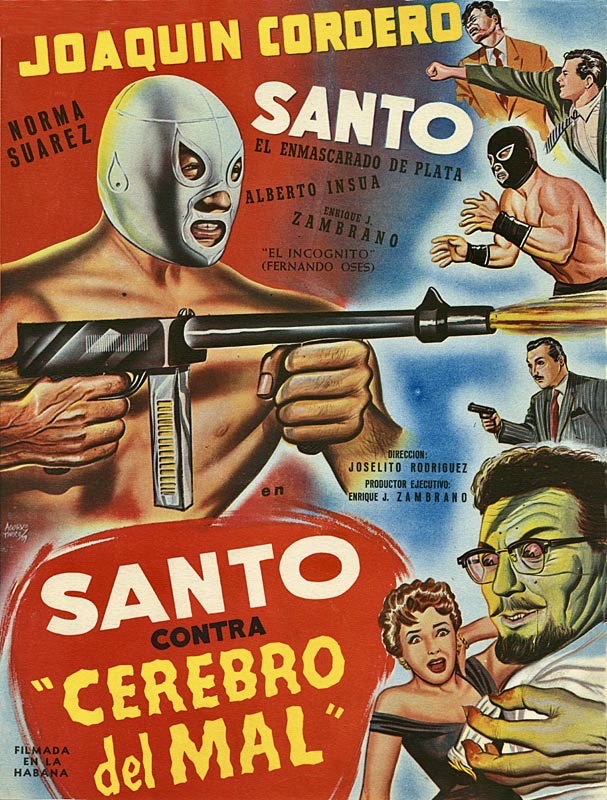

Another superhero who deserves his own hall of fame is Santo, the Mexican wrestler superhero, who NEVER takes his mask off although his foes often attempt it.

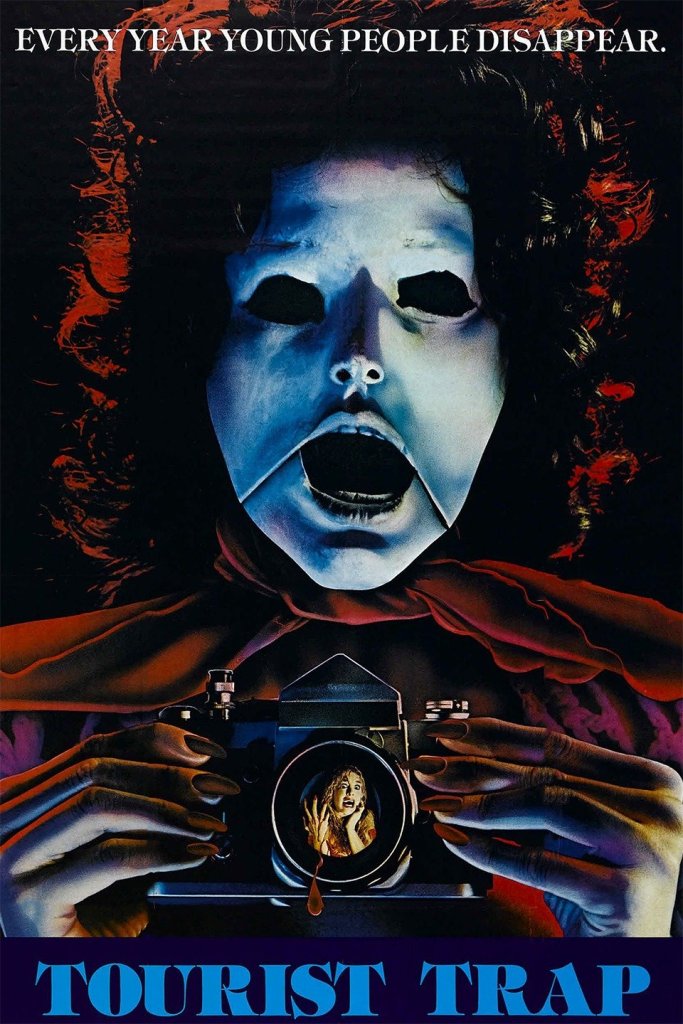

Besides the super heroes and arch villains of pulp cinema and serials are those aberrant cinema icons whose masks personify evil and give the wearer warped delusions of grandeur and empowerment as in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Friday the 13th (Jason), Halloween (Michael Myers aka The Shape), Scream, and Manhunter (The Tooth Fairy).

“The first horror film I remember seeing in the theatre was Halloween and from the first scene when the kid puts on the mask and it is his POV, I was hooked.” – David Arquette (If the star of five of the Scream films saw this movie when it was released in 1978, he was only seven! Where were his parents?)

Sometimes the human face can even be a mask, hiding the most perverse and shocking thoughts and emotions beneath an innocent façade.

When it came to art, Jean Cocteau was famous for demanding this of the creator, especially himself – “Astonish me.” And most would agree that he met this challenge in his own work.

Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet (1932): “Often mistaken for a surrealistic work, this is a carefully constructed artifact, mingling symbol and metaphor to project the anguish, apotheosis and corruption of the struggling artist.” – Amos Vogel, Film as a Subversive Art

“True realism consists in revealing the surprising things which habit keeps covered and prevents us from seeing.”― Jean Cocteau

Sex games and fantasy role playing in exploitation movies often involve the use of masks and disguise and Joseph W. Sarno has capitalized on this in imaginative and kinky ways in such films as Sin in the Suburbs (1964) and Swedish Wildcats (1974, aka Every Afternoon).

Regarding Sin in the Suburbs, Sarno said, “The story happened in upstate New York – I’m not going to give you the name of the town. These men and women – all comparatively wealthy people – wore black hoods and cloaks (but were naked underneath) and would have group sex without knowning who their partners were.” (from an interview featured in Incredibly Strange Films (Re/Search #10).

Could it be that Stanley Kubrick was influenced by Joe Sarno for his masked orgy sequence in Eyes Wide Shut (1999)?

Faces that could never find acceptance in normal society need a disguise….though the solutions may often seem like band-aids to the horrific reality.

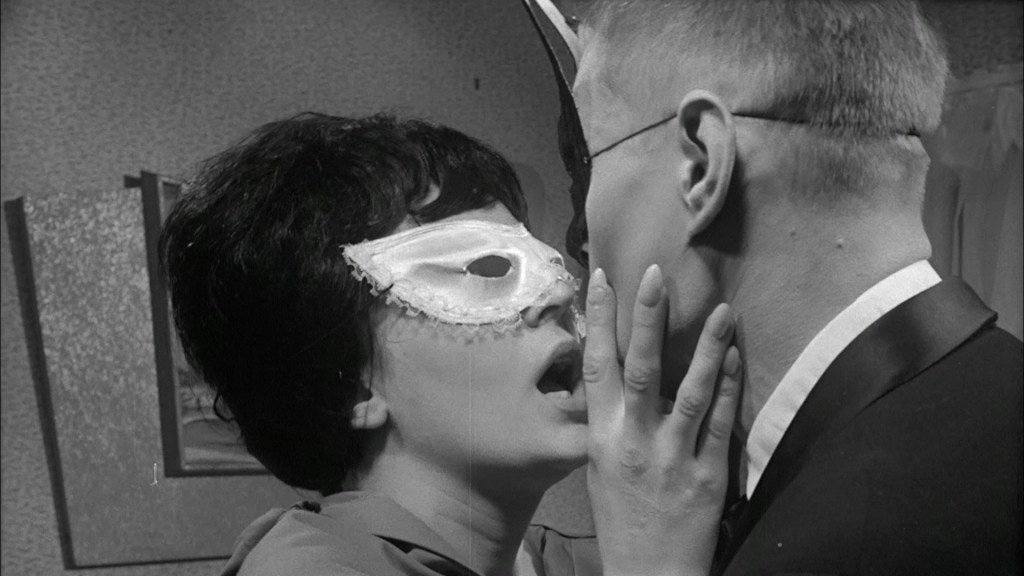

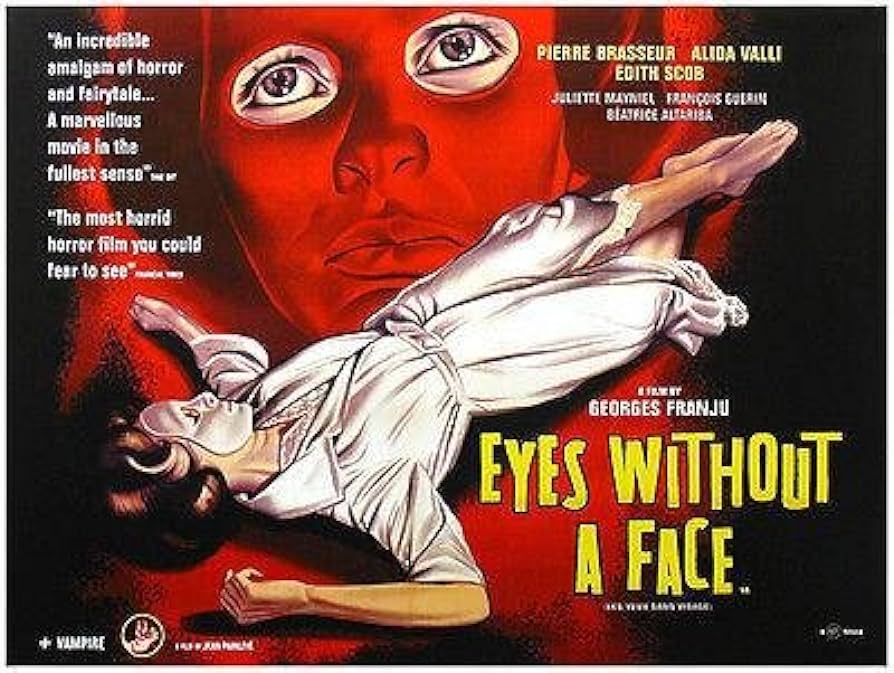

“George Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1959) is for me the most chilling expression in cinema of our ancient preoccupation with the nature of identity. Its core motif is the mask, here an uncanny thing of smooth, hard plastic worn by a young woman to conceal a face destroyed in an auto accident. Her name is Christiane; her father, Dr. Genessier, an eminent Parisian surgeon, is obsessively engaged in an attempt to reconstruct that face. But his cosmetic project is a travesty of the impulse to heal, and Christiane, despite her disfigurement, remains in possession of what her father has lost, if he ever had it – a spiritual faculty, an idea of the good: a soul.” – Patrick McGrath (from the liner notes of the Criterion Collection edition of the film).

My name was not always Sardonicus, and I did not always wear a mask.” – Guy Rolfe as Mr. Sardonicus (1961).

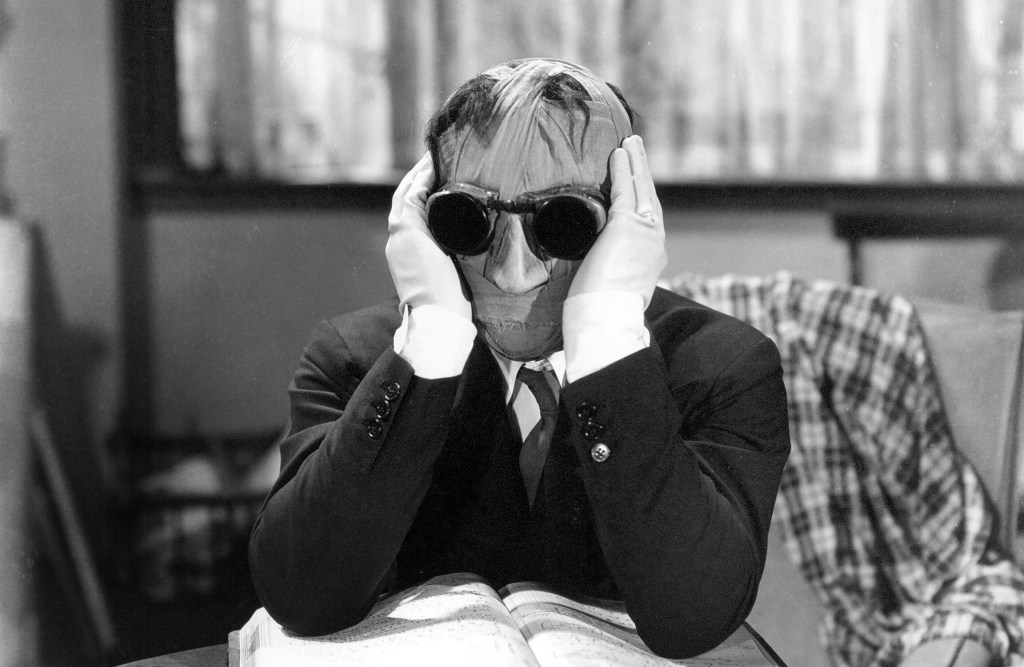

As we have had to re-learn in recent years, masks can be protective devices, protecting you from toxins, germs and disease.

“You’re not the only lonely man. Being free always involves being lonely. Just there is a mask you can peel off and another you can not.” – The psychiatrist in The Face of Another (1966).

Masks can also be implements of torture.…and even imprisonment.

For heist thrillers and murder mysteries, masks are often a necessity to protect both the instigators of a crime and the witnesses.

Sometimes a mask has only one meaning: To Frighten and Terrify!

A mask can also make you laugh.

But never underestimate the power of a mesmerizing disguise in the pursuit of romance.

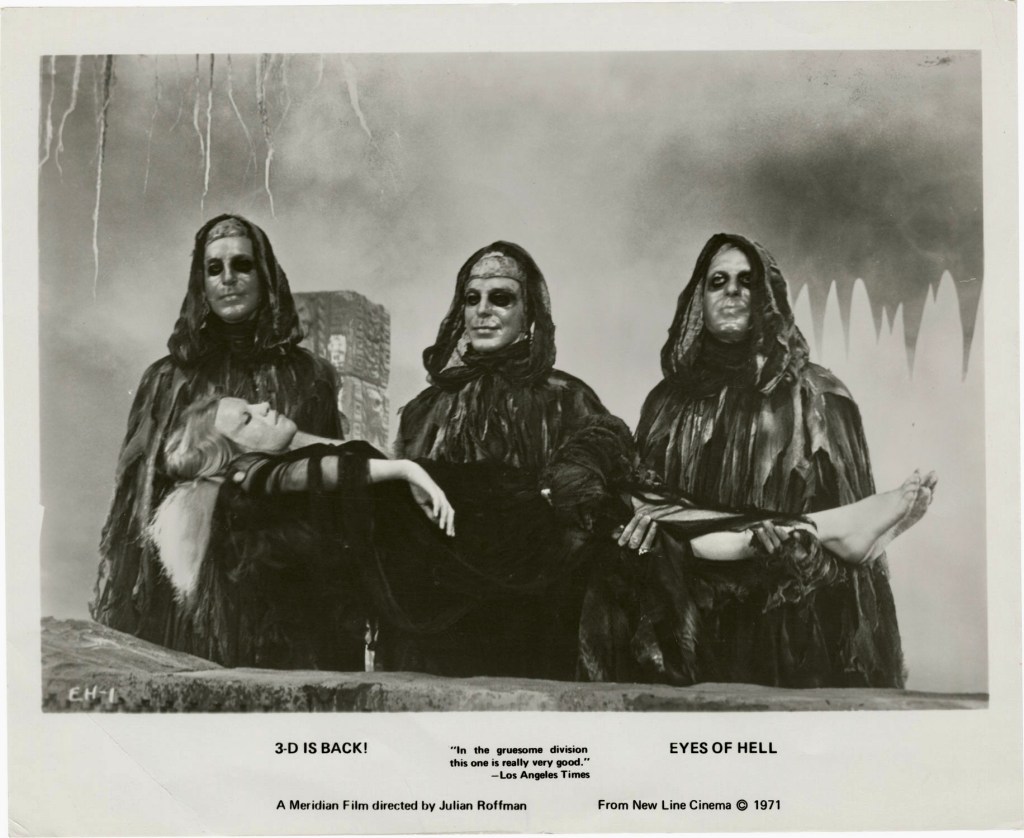

Masks can even serve as the box office gimmick for the featured movie.

Let us not forget some of the more famous Oscar nominated movies in which masks play an important part or figure prominently in key scenes.

Audrey Hepburn and George Peppard in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), nominated for five Oscars including Best Actress and Best Art Direction-Set Direction.

Tom Hulce as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Amadeus (1984), nominated for 11 Oscars including Best Makeup and Best Costume Design.

Jim Carrey in The Mask (1994), nominated for Best Visual Effects, and co-starring Cameron Diaz.

Laura Dern and Eric Stoltz in Mask (1985), which won the Oscar for Best Makeup. Peter Bogdanovich’s film is based on the true story of Rocky Dennis (1961-1978), a boy who suffered from an extremely rare bone disorder known as craniodiaphyseal dysplasia aka Lionitis.

Last but not least, let us not forget the use of masks in theater, be it a Japanese kabuki performance or a Greek drama in which characters often appeared in masks expressing a fixed emotion such as grief or rage.

Other links of interest:

https://www.nycastings.com/unleashing-the-power-of-masks-in-theater-film-and-television/

https://www.halloweencostumes.com/blog/p-922-history-of-horror-masks.aspx