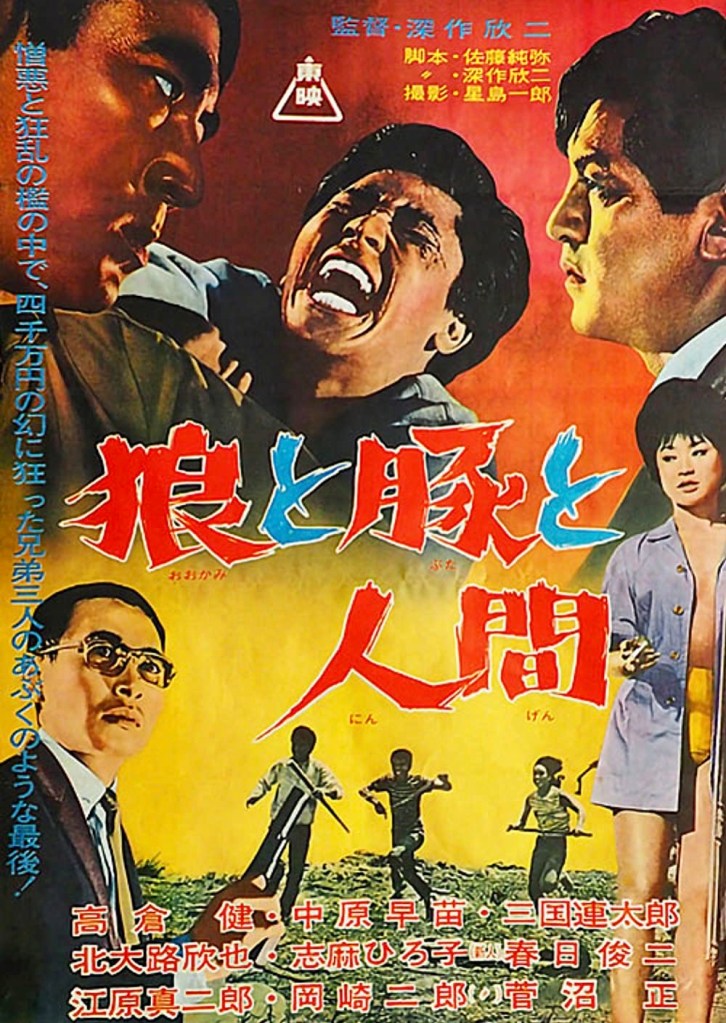

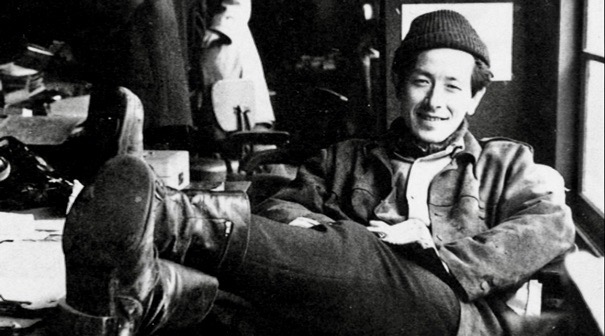

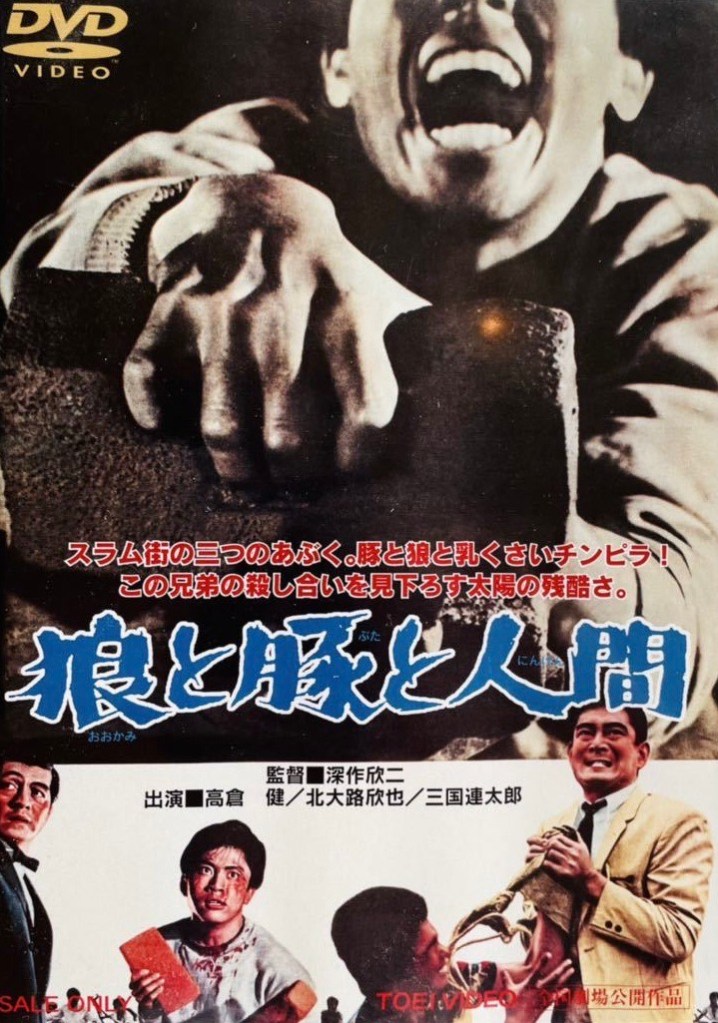

Among the many post-WW2 Japanese filmmakers who emerged in the 1960s and hit their stride in the seventies, Kinji Fukasaku was one of the most prominent and critically acclaimed directors in his own country but didn’t start to acquire a growing fan base in the U.S. until after 2000 when some of his masterworks began to appear on DVD such as the yakuza epic Battles Without Honor and Humanity aka The Yakuza Papers (1973), which launched a five-film franchise, and Battle Royale (2000), a controversial futuristic fable about institutionalized violence against problem teenagers. Over the years, Fukasaku has dabbled in numerous film genres from historical drama (Under the Flag of the Rising Sun, 1972) to sci-fi (Message from Space, 1978) and comedy (Fall Guy, 1982), but he is best known from his crime dramas, especially those which popularized the jitsuroku eiga genre. His documentary-like dramatizations based on real crimes often depicted yakuza figures as ruthless men operating without “honor and humanity” (in the title words of his breakthrough film). Even prior to his trend-setting crime thrillers of the mid-seventies, Fukasaku was turning out edgy, innovative work and Okami to Buta to Ningen (English title: Wolves, Pigs and Men) from 1964 is an explosive, nihilistic tale which qualifies as a rough-hewn, early masterpiece.

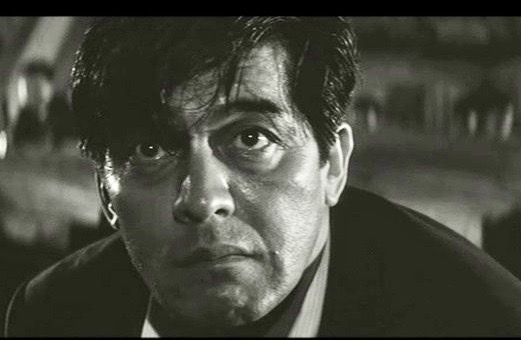

Over the arresting opening credits, a narrator provides the backstory of three brothers growing up in the slums. The oldest son Ichiro (Rentaro Mikuni) and the middle son Jiro (Ken Takakura), left home and abandoned their mother and younger brother Sabu (Kin’ya Kitaoji) to fend for themselves. Ichiro became a prominent businessman and nightclub owner due to his association with the yakuza-run Iwasaki Group while Jiro became a two-bit criminal who served jail time for robbery. The main story of Wolves, Pigs and Men begins as Jiro returns home from prison in time to see Sabu transporting his mother’s coffin to the crematorium.

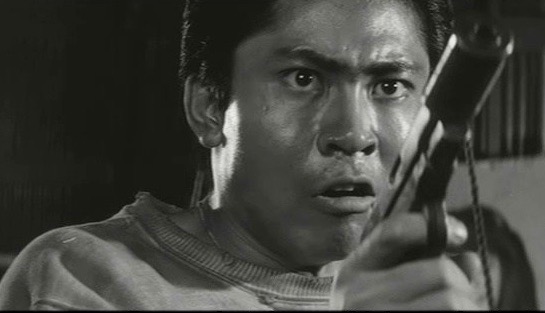

Sabu blames his two older brothers for his miserable, impoverished upbringing and being saddled with a sickly mother. As a result, Sabu has become a bitter, rebellious delinquent who runs wild with a close-knit group of fellow hellions. The hand-to-mouth extremity of Sabu’s existence is depicted in a scene where he and his pals gleefully hunt feral dogs at a garbage dump. They catch one and beat it to death (offscreen) before carrying the body back to their hovel where they prepare it for a stew. Proclaiming their freedom from society, this rag-tag group celebrate their anti-everything status through impromptu, finger snapping singalongs and frenzied dancing in the manner of some West Side Story-like wannabes. But their independence is soon compromised by Jiro, who plots with Mizuhara (Hideo Murota), his partner-in-crime, to involve Sabu and his friends in a risky heist from the Iwasaki clan before betraying the teenagers.

As this is unfolding, Ichiro is summoned by his yakuza benefactor and told he needs to force his troublemaking brother Jiro to leave to town before he causes more trouble and attracts the attention of the police. Even though he receives money to relocate, Jiro ignores Ichiro’s warning and moves ahead with his robbery scheme, which takes place in a crowded train station lobby.

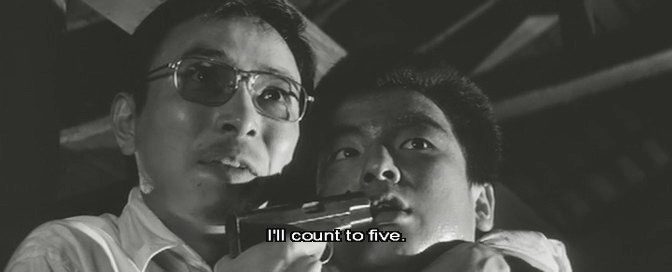

[Spoilers ahead] The heist comes off successfully but the double-crosses begin immediately with Sabu realizing the two stolen suitcases (one containing drugs, the other money) equals a much larger sum than Jiro had told them and they are being duped. Sabu hides them in an undisclosed location but when he returns to his gang’s hideout, Jiro, his mistress Kyouko (Sanae Nakahara) and Mizuhara are in charge and Akira (Seiichi Shisui), one of Sabu’s pals, is already murdered with the others being terrorized.

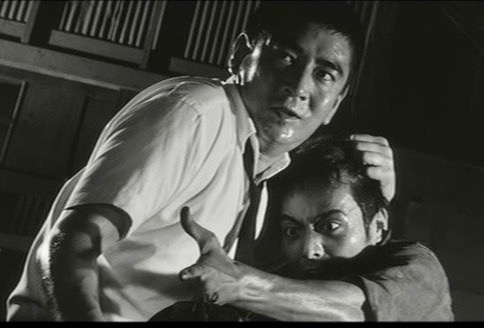

Jiro and Mizuhara subject Sabu to torture, thinking he will reveal the hiding place of the stolen suitcases, but he won’t budge so the duo try more extreme measures on Sabu’s friends including the use of a finger-crushing vise. Meanwhile, Ichiro races against time to find the gang’s hideout and retrieve the stolen property before the Iwasaki members find them first. Of course, it all spirals out of control with bleak consequences for everyone in classic noir fashion.

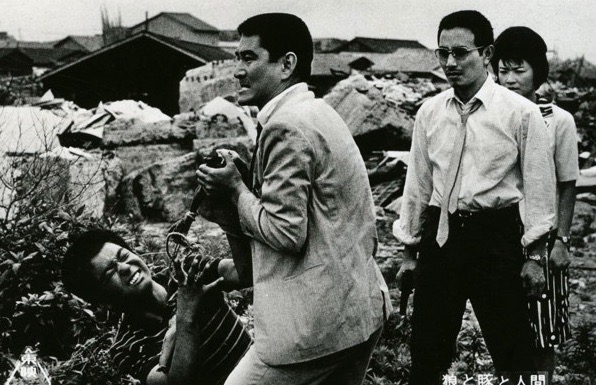

Filmed in the slums of Tokyo in stark black and white Toeiscope by cinematographer Ichiro Hoshijima, Wolves, Pigs and Men is grounded in a depressingly realistic milieu that doesn’t glamorize or romanticize criminals or the yakuza. According to the entry in The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: The Gangster Film (edited by Phil Hardy): “With films such as these Fukasaku quickly acquired the reputation of making the most cynically violent yakuza pictures, debunking the notion of the honourable yazuka, not necessarily because the yakuza were thugs but because honor was no longer an option in a Japan ruled by businessmen and corrupt politicians.”

Compared to other yakuza flicks of its era, Wolves, Pigs and Men is strong stuff indeed featuring brutal violence including the rape of Mako (Hiroko Shima), the sole girl in Sabu’s gang, and an overwhelming sense of hopelessness. Fukasaku employs some stylistic devices such as freeze frames, jump cuts and disorienting camera angles to capture the increasingly desperate behavior of the protagonists. Even more impressive is the pulsating, eclectic music score by Isao Tomita which blends bebop jazz, surf guitar grooves and easy listening lounge music into an atmospheric melange.

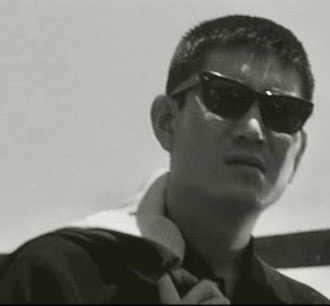

None of it would work as well, however, without the impressive cast assembled here and the main standouts are the three actors portraying the brothers and Hideo Murota as the sadistic and treacherous Mizuhara. Ken Takahura as Jiro is particularly effective as the most amoral of the lot, who learns too late to put family before personal interests. He would develop a much more hardened, tough guy persona in later films such as Teruo Ishii’s Abashiri Bangaichi (1965), his breakout feature, and Kiyoshi Saeki’s Brutal Tales of Chivalry (1965). His cool iconic presence was later used to memorable effect in such Hollywood crime dramas as Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza (1974) opposite Robert Mitchum and Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (1989) with Michael Douglas.

Wolves, Pigs and Men has been one of the more difficult Fukasaku movies to see in the U.S. but, in 2015, a print was shown at the New York Asian Film Festival at Lincoln Center where it was described in the program notes as mixing “social criticism, American noir, [and] French New Wave influences.” Marc Walkow of Film Comment also wrote about the film, calling it a “jazzy, fatalistic black-and-white tale of brotherhood that borrows heavily from Kubrick’s The Killing” while Chris D., author of Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film, proclaims it, “one of the grittiest, angriest yakuza films ever made in Japan. It’s as potent as any of his later mid-seventies pictures.”

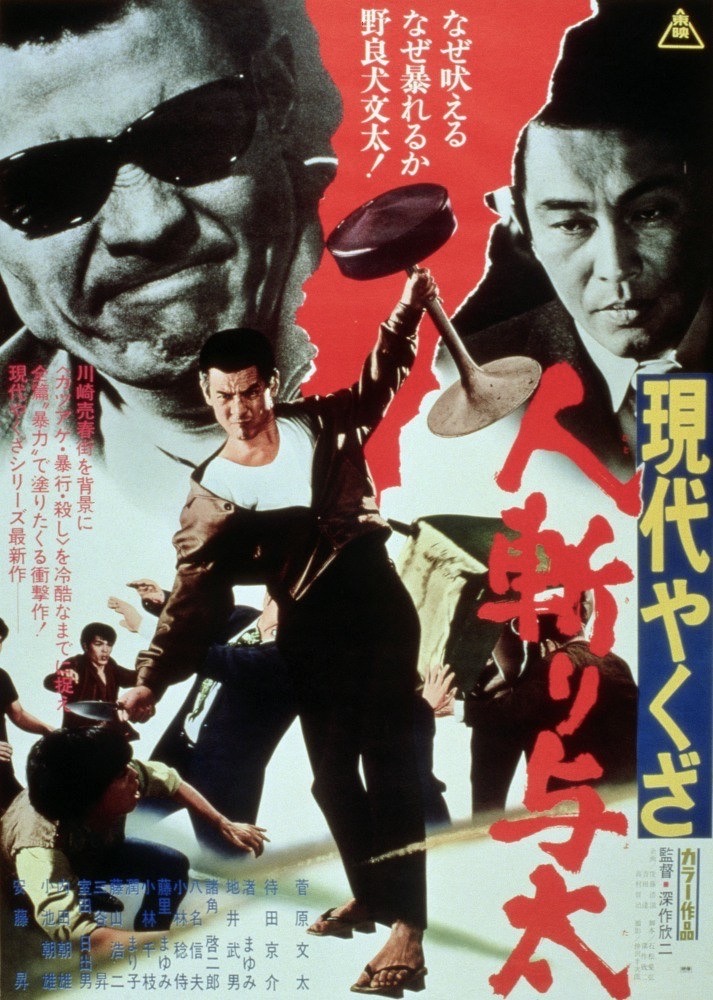

There are some Kinji Fukasaku devotees who feel Wolves, Pigs and Men is less accomplished than his later yakuza thrillers, citing as evidence the low-budget production and a rushed ending in which Jiro has an unconvincing epiphany about his relationship with his brothers. Even Fukasaku has stated in interviews that he felt he didn’t perfect and achieve his vision for a new kind of yakuza film until Gendai Yakuza: Hito-kiri Yota (English title, Street Mobster, 1972) starring Bunta Sugawara.

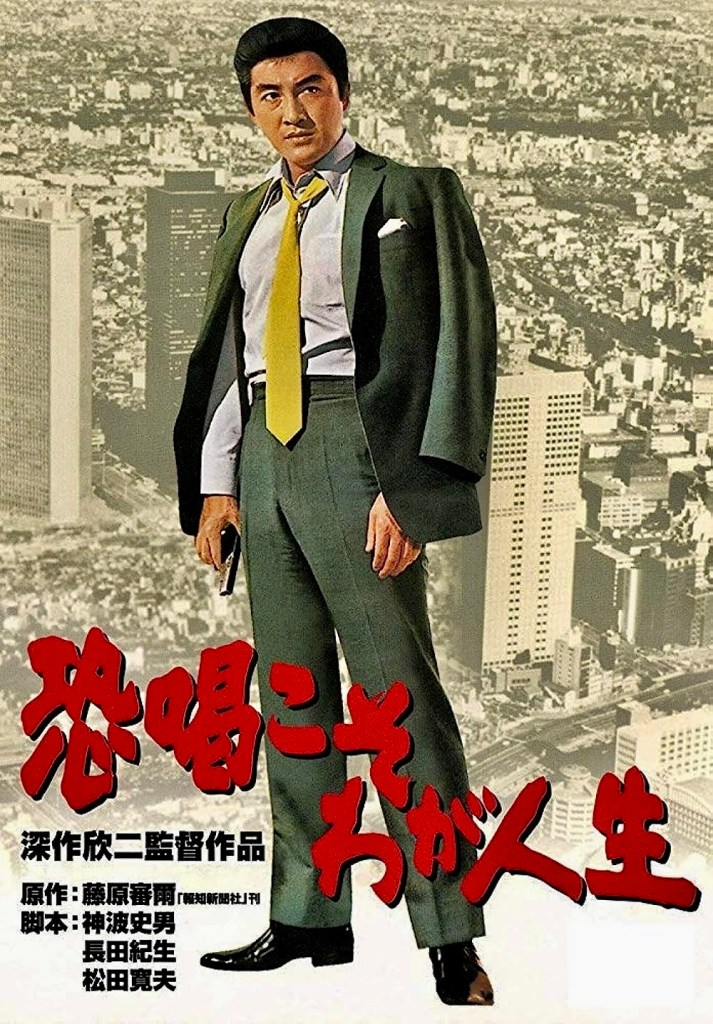

Nevertheless, Wolves, Pigs and Men remains an excellent introduction to the early crime thrillers of Fukasaku and, if you like it, you might want to sample other key works such as Blackmail is My Life (1968), If You Were Young: Rage (1970) and Sympathy for the Underdog (1971) before moving on to the director’s maximum opus, Battles Without Honor and Humanity. Fukasaku considered the latter one of his favorite efforts and never tired of discussing it, Black Lizard (1968) or Battle Royale among critics and fans.

Regarding his often grim, realistic portrayals of yakuza life, Fukasaku said this in an interview with Chris D.: “Producers complained to me many times, “Why do your movies get so dark?” However, if I ask them: “Do you think it’s ok for the main character to get this happy or unrealistic ending?”, even the producers cannot say yes….I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s impossible to have a happy ending today. This is the biggest problem facing mankind now, and I don’t have a solution for the future.” The director died in January 2003 at the age of 72 while in production on the sequel Battle Royale II, which was completed by his son, Kenta Fukasaku.

Wolves, Pigs and Men is not currently available as a domestic release in the U.S. but you might be able to purchase an import DVD (no English subtitles) from online sellers in Japan if you own an all-region DVD player. This would be an ideal pick-up title for an enterprising Blu-ray distributor like Arrow Films or Radiance Films.

Other links of interest:

http://eigageijutsu.blogspot.com/2011/03/interview-with-kinji-fukasaku.html

http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/kinji-fukasaku/

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/kinji-fukasaku-125304.html

https://variety.com/2014/film/news/japanese-actor-ken-takakura-dies-at-83-1201358969/

https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/nyaff-rep-highlights/