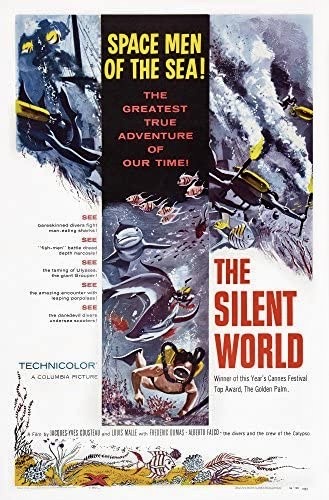

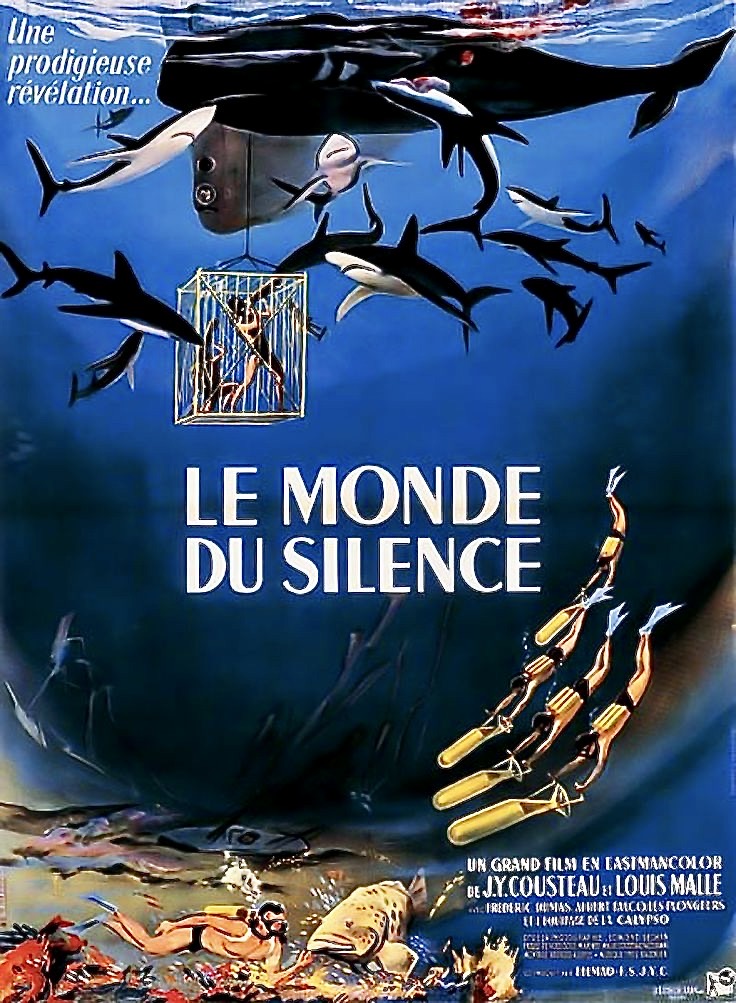

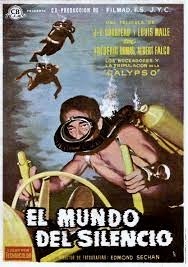

Jacques-Yves Cousteau was undoubtedly one of the greatest explorers of the 20th century but what he discovered was a world most people had never seen before and it was hiding in plain sight under the ocean. His scientific innovations to deep sea diving and his never-before-seen underwater cinematography introduced most people to marine life, behavior and landscapes that were just as strange, beautiful and mysterious as life on another planet. Although he had made numerous short documentaries on the sea throughout the forties starting with Par Dix-huit Metres de Fond in 1943, it was feature length non-fiction film debut, The Silent Sea (Le Monde du Silence, 1956), co-directed with Louis Malle, that first attracted international attention and inspired school kids to want to become explorers, photographers and oceanographers. Seen today, the film is still a fascinating introduction to Cousteau’s world but, like some nature documentaries, it presents images of unearthly beauty mixed with cruelty and violence that wouldn’t be out of place in a Mondo Cane-like exploitation expose. It also presents a more pristine world under the sea before oil spills, global warming and overfishing helped reduce marine life as well as eradicating entire species of fish.

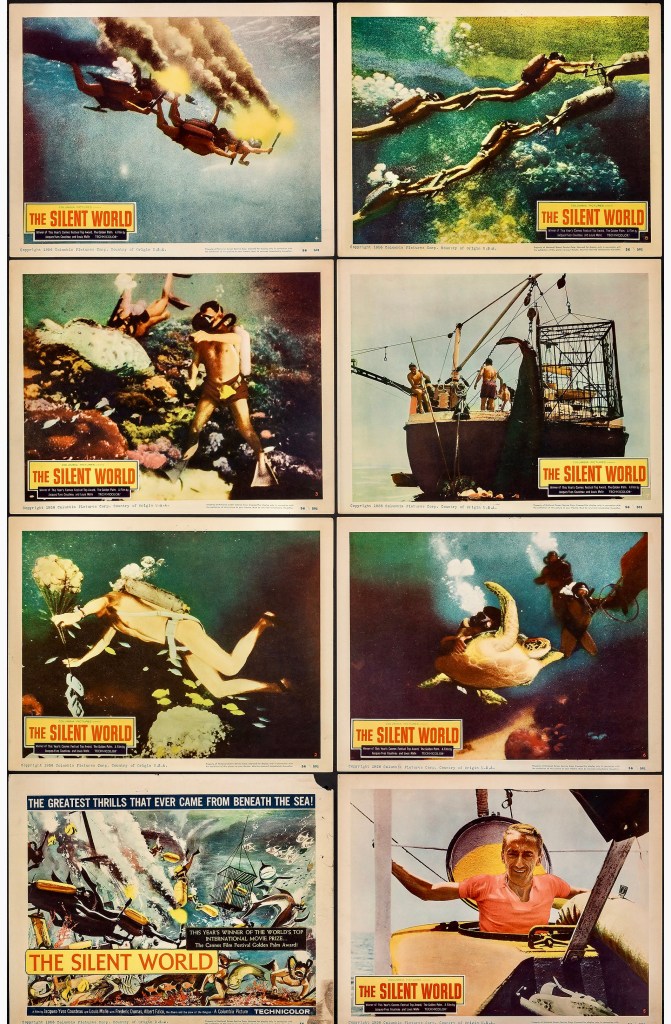

Cousteau’s film opens with the following narration (it was dubbed into English for the U.S. release in most markets) as several divers descend to the ocean floor: “This is a motion picture studio 165 feet under the sea. These divers wearing the compressed air aqualung are true spacemen swimming free as fish. To make this film they roamed deep under the Mediterranean, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean in a mysterious realm – The Silent World.” The documentary then proceeds to document Cocteau and his crew as they explore the wonders of the deep on their ship, the Calypso, but this is not the sort of travelogue that utilizes interviews or talking heads to comment on what we are seeing. Instead, Cousteau provides a narration that is at times playful, apologetic (when things go wrong) and even poetic yet he also allows much of the astounding Technicolor cinematography (by Louis Malle & Philippe Agostini) to speak for itself accompanied by Yves Baudrier’s eerie music score.

The first thing you might notice in The Silent World is that almost all of the Calypso’s all-male crew are remarkably lean and sinewy but smoke cigarettes as they go about their duties. It could be the skipper at the wheel, the cook preparing a meal in the galley or even Cousteau himself with his signature black pipe but smoking is all pervasive. Of course, this is a reflection of the French lifestyle and French cinema has always romanticized smoking on screen but it seems oddly incongruous in this sunny, fresh air environment. Also unusual is the fact that women are never mentioned or seen even though Cousteau’s wife Simone Melchior often accompanied him on his voyages and financed many of his expeditions (She is listed in the credits but I didn’t see her in the film).

Along the journey Cousteau educates the viewer on some of the hazards of deep sea diving such as experiencing “the bends” if a diver rises to the surface too quickly. This is often referred to as decompression sickness (DCS) and is caused by the rapid release of nitrogen gas in the bloodstream that creates bubbles and could result in permanent injury or death. We see one poor diver being placed in a decompression chamber for surfacing too quickly while the rest of the crew go off to feast on dozens of lobsters harvested from an underwater cavern.

Among the many visual splendors of the expedition are scenes of exotic, colorful fish in their element and close-ups of peculiar oddities like the suckerfish (one jokester attaches the creature to the back of a crewmember in a scene). A fleet of more than 100 porpoises leaping alongside the Calypso is another highlight and so is the sequence in which the diving team explores the wreck of a sunken freighter from 1941, now covered in coral, sponges, anemones and other sea life.

Another aspect of the film that is remarkable is the fact that the Calypso never sees or encounters other sea-going vessels. We never see fishing fleets, ocean liners or naval ships in the Mediterranean or other locales. In fact, the only non-crew member we meet is a local native digging for turtle eggs on a remote desert island.

Not everything we experience is idyllic, however, and some of the methods Cousteau used for collecting specimens and investigating sea life are not only harmful but are now outlawed. Cousteau himself would actually apologize later in life for some of the scenes depicted in The Silent World. I’m referring to one scene where a diver hacks off pieces of living coral for samples but much worse is the sequence where the crew uses dynamite to blow up a reef so they collect and study the samples. It is profoundly disturbing to see so many beautiful, unusual fish dying on the deck, especially a bloated pufferfish that discharges water until it deflates into a limp corpse.

Certainly the most notorious and tragic incident in the documentary is the accidental death of a baby sperm whale that gets too close to the Calypso and is badly cut by the ship’s propellers. As the animal slowly bleeds to death, Cousteau decides they should put it out of its misery and harpoon it before finishing it off with a gun. After that the body is left for the sharks to eat and the feeding frenzy is difficult to watch. As if that’s not enough, some of the crew members begin to spear some of the sharks and drag them on deck where they are beaten to death for no good reason. For someone who reveres the sea and its creatures, Cousteau seems to have an anti-shark bias at this stage in his life.

In other scenes that are clearly meant to be playful, the behavior of certain crew members appears questionable or unenlightened. An underwater diver encounters a giant sea turtle and hitches a ride on his back (the animal clearly wants to escape). Later when several crewmen from the Calypso discover numerous tortoises on a desert island they climb on their lumbering creatures and ride them like donkeys.

You also have to wonder why some of the divers would descend to the ocean floor with little bags of meat to feed fish. Although the food attracts a variety of interesting fish, it seems like a good way to also attract human predators as well. An extremely large grouper that the crew nickname Ulysses becomes the star of this segment but becomes so greedy from the feeding that he becomes a nuisance and must be placed in a shark cage.

Despite my negative reaction to certain scenes in The Silent World, it is still a landmark in documentary filmmaking and essential viewing for anyone interested in the arc of Cousteau’s life and achievements. The documentary also shows how far we have come since 1956 in terms of environmental concerns and our understanding of nature. Cousteau’s own evolution as a defender of the environment has been well documented. Some people forget that several of the Calypso’s early expeditions were funded by oil companies. One in particular was funded in 1954 by a British Petroleum company for exploring the seabed off the coast of Abu Dhahi and resulted in offshore drilling. Some of this is covered in Liz Garbus’s 2021 documentary Becoming Cousteau but it also explains why Cousteau became such a passionate defender of the sea in later life. As early as 1971 he began sounding the alarm about the effects of pollution on marine life. In an article for The New York Times entitled “Our Oceans Are Dying,” he wrote “there is only one pollution because every chemical in the air or on land will end up in the ocean.”

It is true that Cousteau’s TV series The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau (1968-1976) and later documentaries became increasingly grim and cautionary portraits of mankind’s abuse of the sea which eventually had trouble attracting corporate sponsors. Still, Cousteau is certainly a hero for our times and his many awards and honors are testament to his numerous achievements – National Geographic Society’s Special Gold Medal (1961), Commander of the Legion of Honour (1972), Officer of the Order of Maritime Merit (1980), U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom (1985), etc.

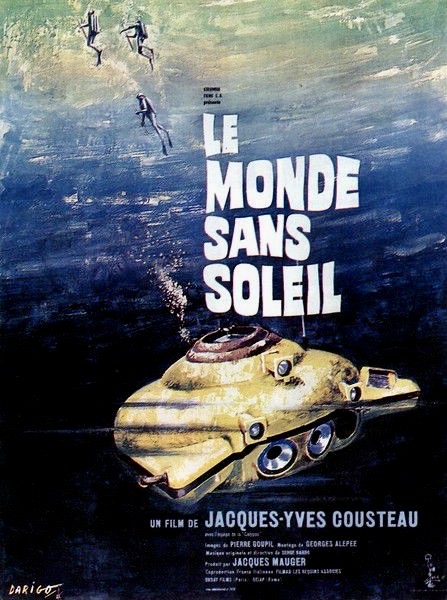

Based on his 1953 best-selling work, The Silent World was the first of Cousteau’s films to win an Oscar for Best Documentary (It also won the Palm d’Or at Cannes). He would later win an Oscar for Best Short Film (The Golden Fish aka Historie d’un Poisson Rouge, 1959) and another Best Documentary Oscar for World Without Sun (Le Monde sans Soleil, 1964). This doesn’t even begin to cover the awards and Emmy nominations he would receive for his television work.

Much of Cousteau’s TV work is available on Blu-ray and DVD but The Silent World appears to be currently out of print in the U.S. You might be able to purchase a French import Blu-ray of it (no English subtitles) if you own an all-region player. The good news is that you can stream the English version of the documentary on Youtube in a better-than-expected transfer.

Come to think of it, The Silent World would actually make a good double feature with Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), a whimsical and touching fictional homage to Cousteau and the Calypso crew which reflects the director’s childhood fascination with the explorer.

Other links of interest:

https://www.easthamptonstar.com/arts/2021107/jacques-cousteaus-true-adventures

https://www.salon.com/2002/07/15/silent_world/