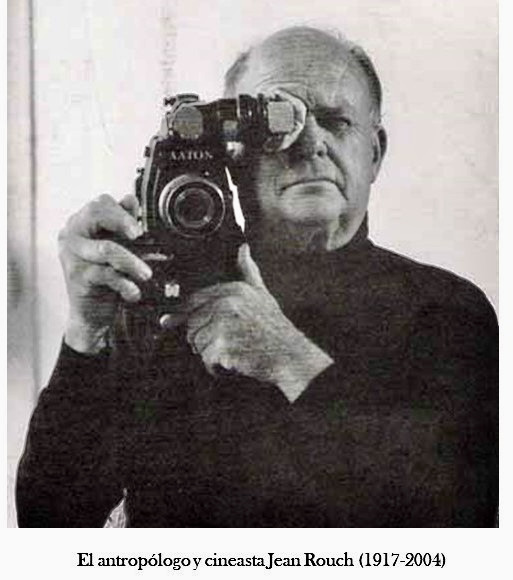

“The camera eye is more perspicacious and more accurate than the human eye,” French filmmaker Jean Rouch once said, and his idiosyncratic documentaries, which were often fusions of reality and fiction, bear this out. Jaguar (1967) is a perfect example of this duality.

Although relatively unknown to American moviegoers, Rouch was a figure of great interest in academic circles and anthropology groups, and extremely influential on the Nouvelle Vague and experimental filmmakers of the 60s. Using a handheld camera when it was still a rarity in filmmaking during the late 1940s, Rouch became internationally renowned for his short films on African customs and rites, with Mad Masters (Les Maitres Fous, 1953), a document of the

Hauka possession cult in Accra, Africa, often singled out as a key work.

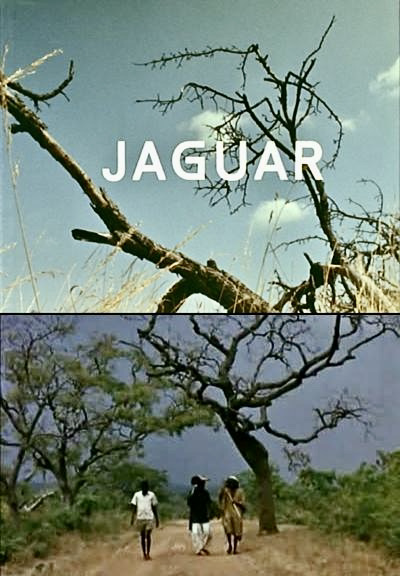

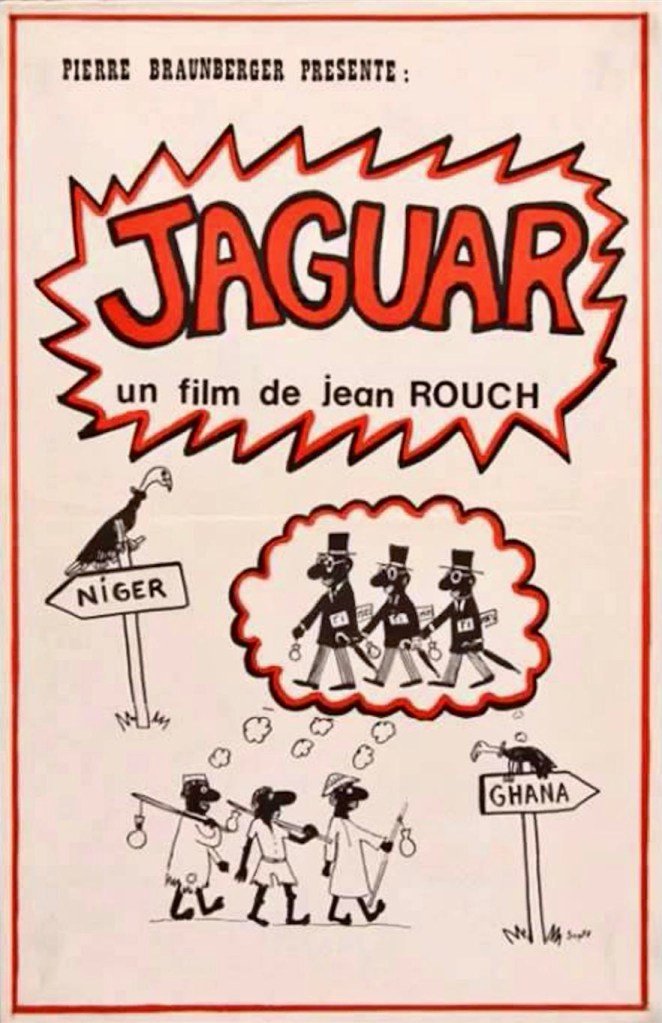

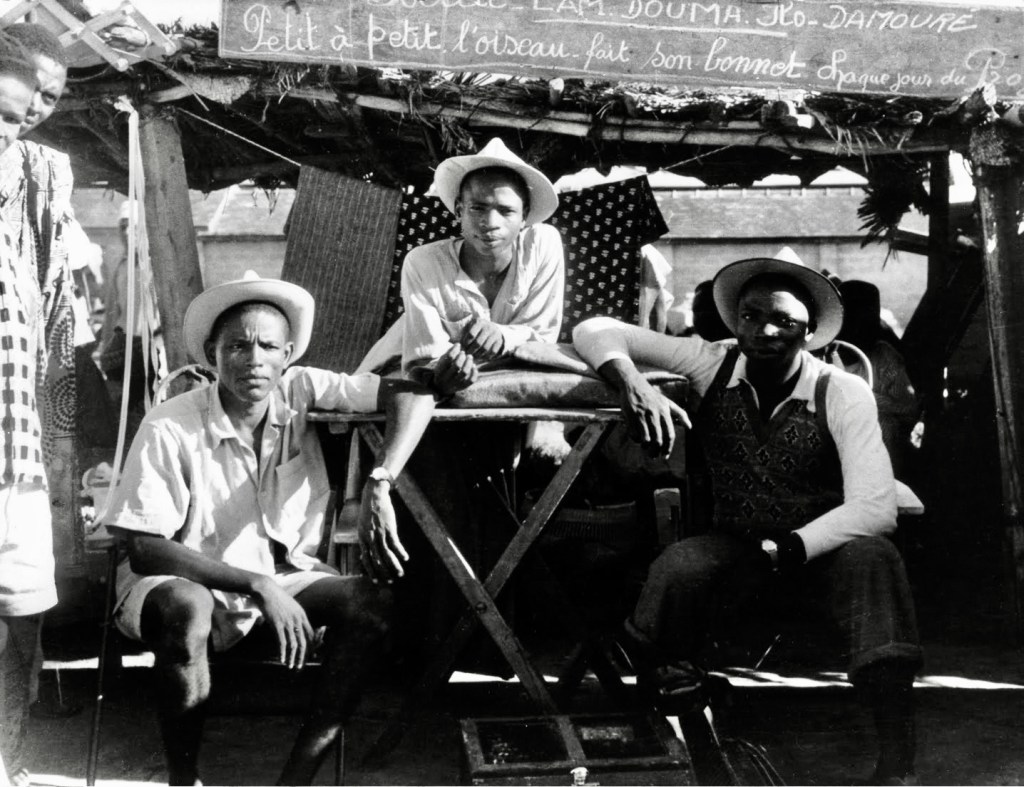

Jaguar is a cinematic journey by three young Nigerian men – Illo, a fisherman, Douma, a farmer, and Lam, a shepherd – who travel from their village to the Gold Coast (modern day Ghana) in search of work and adventure. Their experiences reflect a changing world with marked cultural differences between country folk and city dwellers as well as an ideological split between post-Colonial life and political movements in their native land. What might have become an academic polemic in other hands is crafted by Rouch into a freewheeling, often lighthearted odyssey that is fueled by a sense of spontaneity and surprise.

Unlike the traditional methods used by documentarians like John Grierson and Joris Ivens to convey realism, Rouch made his three protagonists complicit collaborators in the

filmmaking process. For example, in one unusual sequence, the three men pass through a village in which the inhabitants of an African ethnic group known as the Ditamari live a lifestyle not dissimilar from a nudist colony. At first these outsiders dismiss the natives as primitive but then begin to debate and appreciate the customs and traditions of the Ditamari as something unique and even practical. The three travelers’ thoughts are part of Jaguar‘s multi-layered sound design that weaves their interjections into an audio mix that includes regional music, sound effects and off-and-on commentary by Rouch.

“It was shot as a silent film,” Rouch stated, “and we made it up as we went along. It’s a kind of journal de route…my working journal along the way with my camera. We were playing a game…I brought the film back two years later and projected it to the boys in Accra. We improvised the commentary in one day.”

All of the footage for Jaguar was shot in 1954 but Rouch toyed with the narrative for years. Italian director Roberto Rossellini, who helped launch the neorealism movement in post-WW2 Italy, saw rushes of the film in 1955 and persuaded Rouch to have the actors narrate their own story. The result is an original work of art in which the three principles alternate

between playing themselves and fictitious alter egos. If you see the film, you’ll notice that Rouch dedicated it to French actor Gerard Philipe. It was the latter who provided Rouch with the production money he needed to complete the feature.

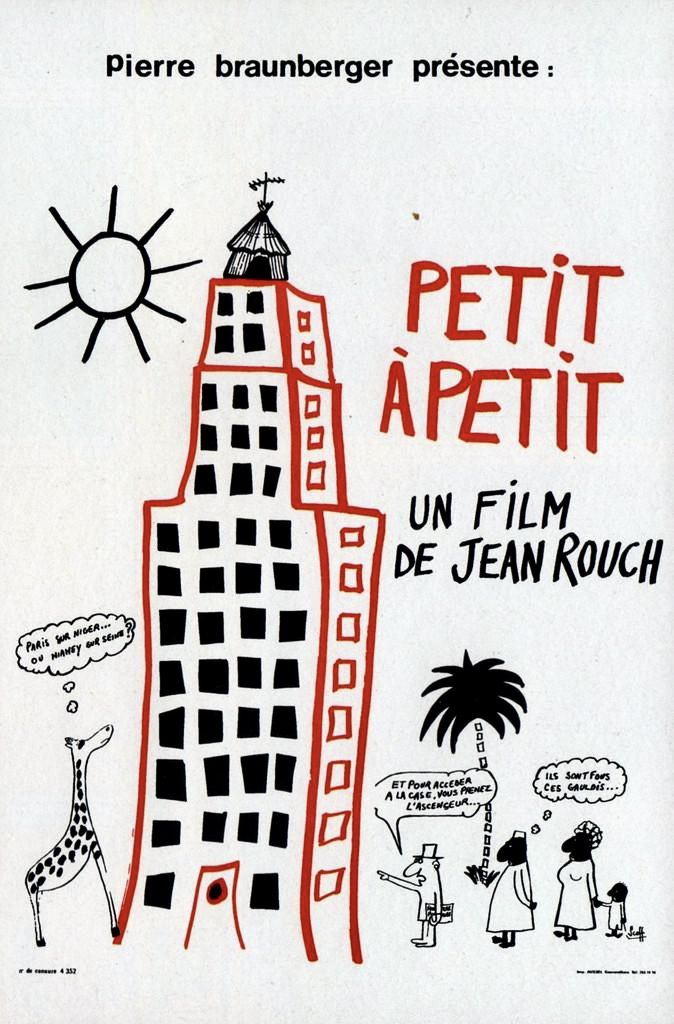

When Jaguar finally premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1967, it was well received by the audience and French film critics but it remains an often overlooked entry in Rouch’s massive filmography of over 100 shorts and features. As an interesting aside, Illo, Douma and Lam would return to play themselves in a 1970 semi-sequel to Jaguar entitled Little by Little (Petit a Petit) in which the trio are running their own import/export business.

I first encountered Jaguar through Film Love, an alternative film series curated by Andy Ditzler in Atlanta, Ga. Ditzler has been operating his series since 2003 and has introduced audiences to such off-the-radar discoveries as Warren Sonbert’s Friendly Witness (1989), Jack Willis’ Civil Rights era documentary Lay My Burden Down (1966) and Normal Love (1963), Jack Smith’s avant-garde costume epic. Helping to put Jaguar in context and dismiss any expectations of a straightforward ethnographic film, Ditzler revealed to me in an interview prior to the screening, “You don’t know when they’re intentionally pulling your leg. I wanted to show it partly because it is very subversive in and of itself. It also takes place against the background of revolution in Ghana; Kwame Nkrumah is coming to power at this time, and you actually see CPP (Convention People’s Party) rallies in the film. It’s not just dropped in as a point of interest. You’re well aware that a revolution is going on at the time they’re filming.”

Not everyone was enamored of Rouch’s work. African director Ousmane Sembene accused him of studying his subjects in the manner of an entomologist, and some critics complained that, as a European with ingrained colonialist ideas about Africa, his viewpoint was compromised. Yet Ditzler points out that Rouch was subverting ethnographic conventions in films like Jaguar. He was addressing issues like “how do we deal with the fact that we’re filming people and being self-reflective about inserting the filmmaker into the film. And making sure everyone knows this is a film.”

Rouch was the antithesis of the stereotypical Westerner who traveled to Africa to steal images and then retreated to a place of safety. He was “way ahead of the curve on that,” Ditzler notes. “He’s wickedly humorous and was deliberately constructing fictions. The films are

very much collaborations. They’re critical and playful at the same time.”

In the case of Jaguar, Rouch himself described it as “a postcard in the service of the imaginary” and even compared it to Surrealist painting. Renowned film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, however, offered a different take:”..the charming and rambling aspects of the narrative are a good dead closer to music than painting – and to the kind of music that takes you places. There’s even a relevant connection here to performance art.”

Jaguar, like most Jean Rouch films, did not have a standard commercial release in U.S. cinemas and the only way to see it was at some repertory film series at a museum like MoMA or a film program curated by the Anthropology Department of a major university. That changed in November 2017 when Icarus Films released the box set Eight Films by Jean Rouch on DVD which included Jaguar and Little by Little. At one time Amazon Prime offered Jaguar as a streaming option and the official Icarus Films website is also still a place to check for availability.

*This is a revised and expanded version of an article that originally appeared on the Burnaway website.

Other links of interest:

https://www.der.org/jean-rouch/content/index.php?id=about_biography

https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1978.80.4.02a00640

http://www.jamesweggreview.org/Articles.aspx?ID=2096

https://www.andyditzler.com/fsm/film_love.htm