From an early age I developed a fascination with film but it wasn’t until college when my film interests expanded beyond American cinema to include international films and more specialized genres like underground, silent, documentary and exploitation movies. A Film History 101 course at the University of Georgia, curated by a drama professor, was partly responsible for that due to his eclectic overview which sampled the early work of Sam Fuller (The Steel Helmet, Park Row), Fritz Lang silents (Die Nibelungen: Siegfried & Kriemhild’s Revenge), the roots of Neorealism (La Terra Trema) and Hollywood studio system gems (George Sidney’s Scaramouche, An Affair to Remember). What made one of the strongest impressions, however, were examples of early Soviet cinema like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera. And my favorite of them all was Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (Russian title: Zemlya, 1930), the third film in a trilogy that included Zvenyhora (1928) and Arsenal (1929).

From an early age I developed a fascination with film but it wasn’t until college when my film interests expanded beyond American cinema to include international films and more specialized genres like underground, silent, documentary and exploitation movies. A Film History 101 course at the University of Georgia, curated by a drama professor, was partly responsible for that due to his eclectic overview which sampled the early work of Sam Fuller (The Steel Helmet, Park Row), Fritz Lang silents (Die Nibelungen: Siegfried & Kriemhild’s Revenge), the roots of Neorealism (La Terra Trema) and Hollywood studio system gems (George Sidney’s Scaramouche, An Affair to Remember). What made one of the strongest impressions, however, were examples of early Soviet cinema like Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera. And my favorite of them all was Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (Russian title: Zemlya, 1930), the third film in a trilogy that included Zvenyhora (1928) and Arsenal (1929).

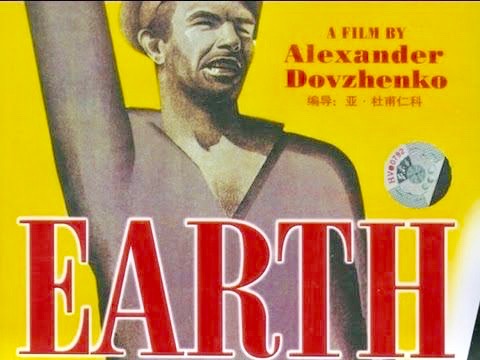

A scene from Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930), the third film in a trilogy by the Ukrainian director.

Earth was the final silent film from Ukrainian director Dovzhenko and is generally considered his greatest work and a landmark of early Soviet revolutionary cinema. The story is a simply told but lyrical celebration of life in a Ukrainian village. On the eve of collectivization in the Ukraine, a young farmer – Vasili – has a unique vision: the village council will buy a tractor to be shared among the farmers. The rich landowners – “kulaks” – are threatened by Vasili’s proposal and the idea of any sort of unity among the peasant farmers. Eventually, Vasili meets a tragic end on a moonlit night (one of the film’s most visually impressive sequences) but the dawn brings forth the promise of prosperity to the poor village.

While the idea of watching a silent film that revolves around one farmer’s campaign for a communal tractor sounds like a bad cliche of Soviet cinema, Earth is surprisingly poetic and visually astonishing at times. Renown film critic Georges Sadoul in his Dictionary of Films wrote “Though its basic story (collectivization in the Ukraine and kulak defiance) is very much set in its own time, Earth has universal themes that transcend this: the fruitfulness of the earth, its annual rebirth, life, love and death. It is Dovzhenko’s portrayal of these themes that gives Earth its moving lyrical power…..The deceptively simple photography, reducing every element to its essential meaning, has incredible beauty and brilliantly captures the sense of vast plains, fruit trees, and enormous sunflowers under an overpowering sky. And over everything lies Dovzhenko’s love for his native Ukraine.”

A masterpiece of early Soviet cinema, Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth aka Zemlya (1930) is probably the most visually stunning propaganda film ever made.

Dovzhenko later said in a 1930 interview that the reason he made Earth was because “I wanted to show the state of a Ukrainian village in 1929, that is to say, at the time it was going through an economic transformation and a mental change in the masses.” He also added that, “It is necessary to both love and hate deeply and in great measure if one’s art is not to be dogmatic and dry. I work with actors, but above all with people taken from the crowd. My material demands it. One should not be afraid of using nonprofessional actors because one should remember that everyone at least once can act out his own role on the screen.”

A scene from Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth aka Zemlya (1930), a lyrical celebration of collective farming.

When Earth first played movie houses in Russia, it quickly developed a controversial reputation, dividing critics and government officials over its merits. Those who condemned it felt that the film’s intense lyricism was politically incorrect and did not fully advance the drive for agricultural collectivization. Demian Bedny, who was officially recognized as the “Kremlin poet,” attacked the film for being overly “philosophical.” “I was stunned by [Bedny’s] attack,” Dovzhenko later wrote, “so ashamed to be seen in public, that I literally aged and turned gray overnight. It was a real emotional trauma for me. At first I wanted to die.”

Demian Bedny, who was officially recognized as the “Kremlin poet,” attacked the film for being overly “philosophical.” “I was stunned by [Bedny’s] attack,” Dovzhenko later wrote, “so ashamed to be seen in public, that I literally aged and turned gray overnight. It was a real emotional trauma for me. At first I wanted to die.”

Stalin had stated that “for us the most important of the arts is the cinema” and he commandeered it as a propaganda tool. But if Marxists expected Earth to dramatize the economic necessity of destroying the kulak as a class, Dovzhenko’s approach avoided overt political dogma despite some satire of not just the kulak but the church. Instead, the film’s serene, meditative tone celebrated mother nature as the film’s true focus.

A grief-stricken woman rips off her clothes in a scene from Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930), which was censored in some prints.

Before Earth was released abroad, Russian censors removed at least three offending sequences – the grief-stricken fiancee ripping her clothes off, a woman giving birth during a funeral, and a tractor radiator being filled with urine. Even in an edited version, however, Earth was universally praised during its premieres in Paris, Berlin and New York City. And Dovzhenko had another reason to be happy. It was during this period that he married Yulia Solntseva who would become his most important collaborator. Later, during World War II, it was reported that the Germans destroyed the negative of Earth but luckily a copy of the original release print was found and preserved. The film would eventually be cited as a major inspiration for such directors as Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Parajanov.

Earth was available on DVD from Image Entertainment and paired with the 1937 Sergei Eisenstein short Bezhin Meadow in 2002. In 2003 Kino Video released a special DVD edition of Earth and two co-features, Vsevolod Pudovkin & Mikhail Doller’s The End of St. Petersburg (1927) and Pudovkin & Nikolai Shpikovsky’s Chess Fever (1925). At this time, the film is not yet available on Blu-Ray but it seems like the perfect candidate for The Criterion Collection treatment.

*This is an expanded and revised version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

*This is an expanded and revised version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

Other websites of interest:

http://kinoglazonline.weebly.com/dovzhenko-aleksandr.html

http://rayuzwyshyn.net/dovzhenko/Earth.htm

http://www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk/reviews/2010/08/01/earth/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A-E57eyjoao