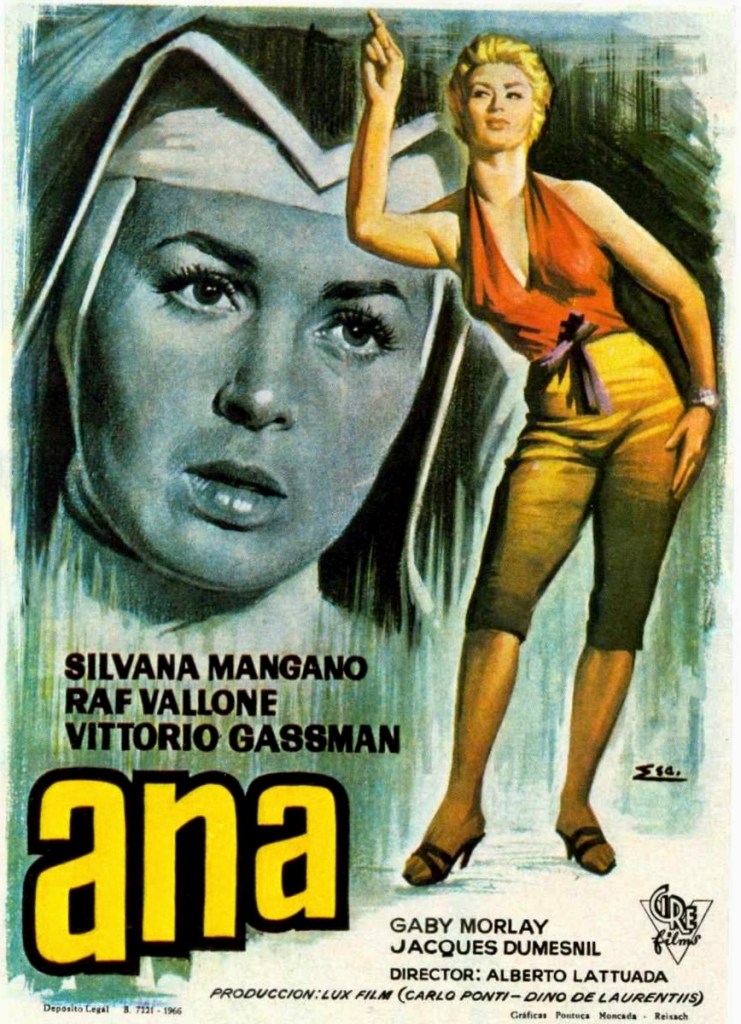

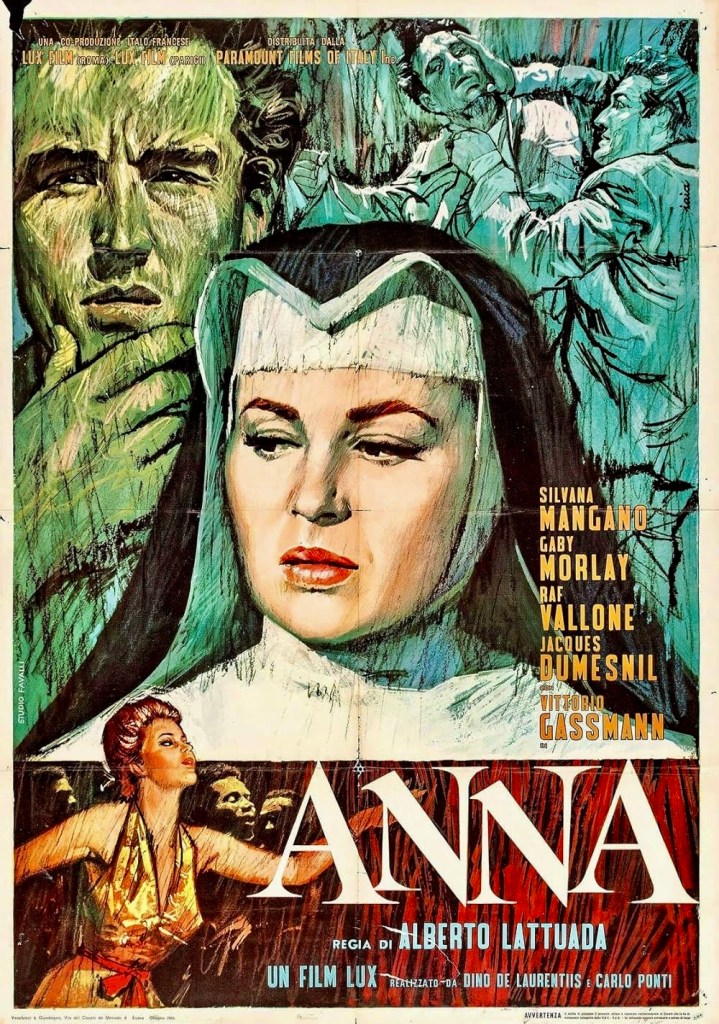

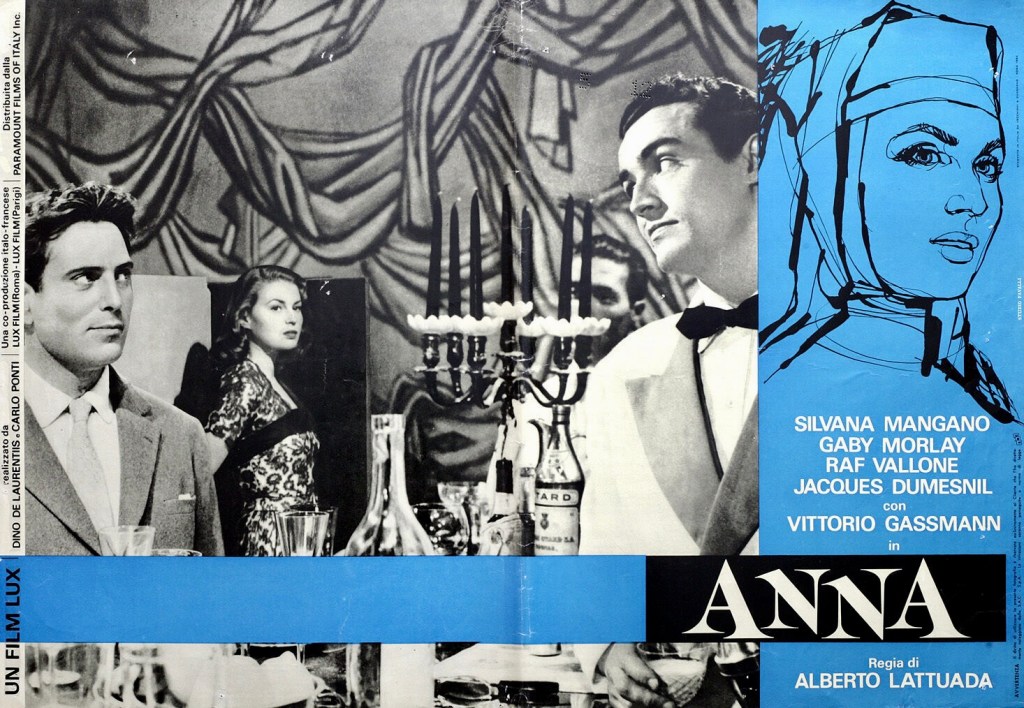

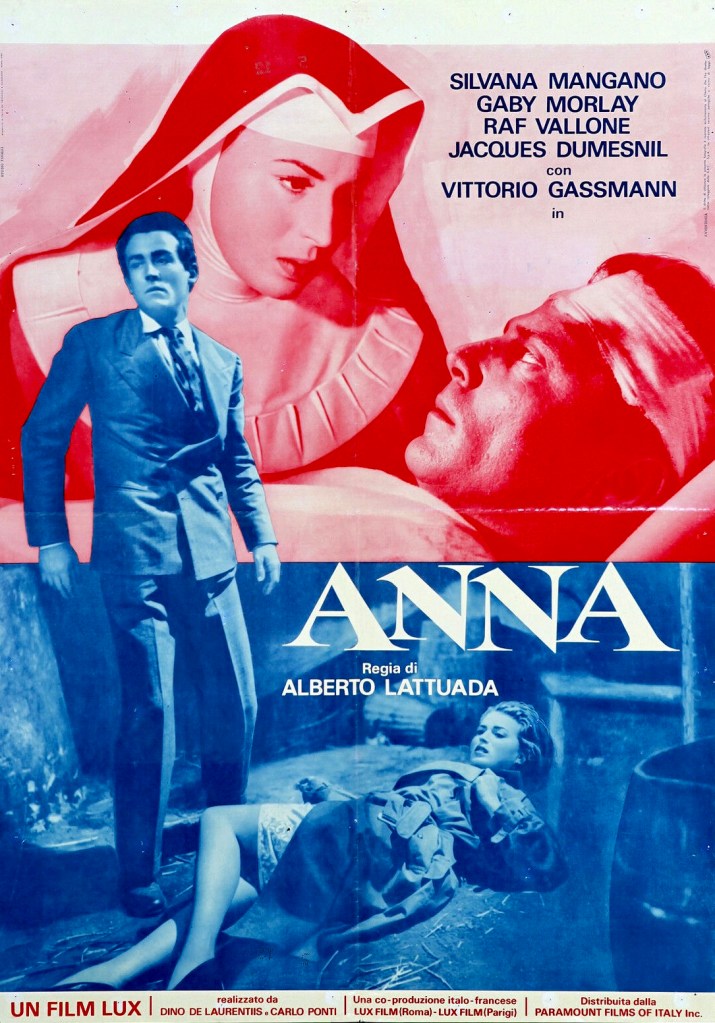

He was a prominent and commercially successful director for most of his career but Alberto Lattuada is often overlooked when film scholars discuss the important Italian filmmakers of the postwar era. Part of the problem was that he was hard to pigeonhole due to his eclectic filmography yet he always seemed to have his finger on the pulse of Italian popular culture. And his films reflected the changing times and interests of his generation from the birth of the neorealism movement [Il Bandito aka The Bandit (1946), Senza Pieta aka Without Pity (1948)] to literary adaptations [Il Mulino del Po aka The Mill on the Po (1949), La Steppe aka The Steppe (1962)] to popular entertainments focused on female protagonists like Guendalina (1957) featuring Jacqueline Sassard in her first starring role and Nastassja Kinski in Cosi come sei aka Stay as You Are (1978). Lattuada might be just a footnote in film history due to his collaboration with Federico Fellini on Luci del Varieta (English title: Variety Lights, 1950) but Italian audiences flocked to his films and they made his 1951 melodrama Anna starring Silvana Mangano in the title role into a major box office smash.

Seen today, Anna looks like an Italian version of a Hollywood soap opera targeted for female audiences but it was actually part of a popular trend in the country’s cinema of the late forties/early fifties. It was a style of overheated social drama addressing sexuality, morality, social issues and Catholicism made popular by Raffaello Matarazzo in such character driven melodramas as Chains (1949), Tormento (1950) and Nobody’s Children (1952). Anna certainly shares similarities with Matarazzo’s audience-pleasing entertainments but it is also of interest to film buffs for entirely different reasons.

It was co-produced by Dino De Laurentiis and Carlo Ponti as a star vehicle for Silvana Mangano, who became an international star after her performance in Giuseppe De Santis’s Bitter Rice (1949). A tale of female workers toiling in the rice fields of the Po Valley, the film is less of a key neorealism film that a pulpy melodrama that capitalized on the earthy sex appeal of its cast, especially Ms. Mangano (who married De Laurentiis the same year). Anna, however, accents Mangano’s versatility as an actress by casting her in a variation of the Madonna/whore stereotype so prevalent in melodramas of that era. She gets to sing, dance, carry on a passionate self-destructive affair with a lowlife but also suffer, repent and try to redeem herself through helping others through her faith.

The film is also noteworthy for reteaming Mangano with her male co-stars, Raf Vallone and Vittorio Gassman, from Bitter Rice. Both of whom were rivals for her in the former film. The other intriguing aspect of Anna is the film’s mixture of genre types combining film noir and soap opera elements with an almost documentary-like approach to the daily operation of a big city hospital in Milan where Anna is employed.

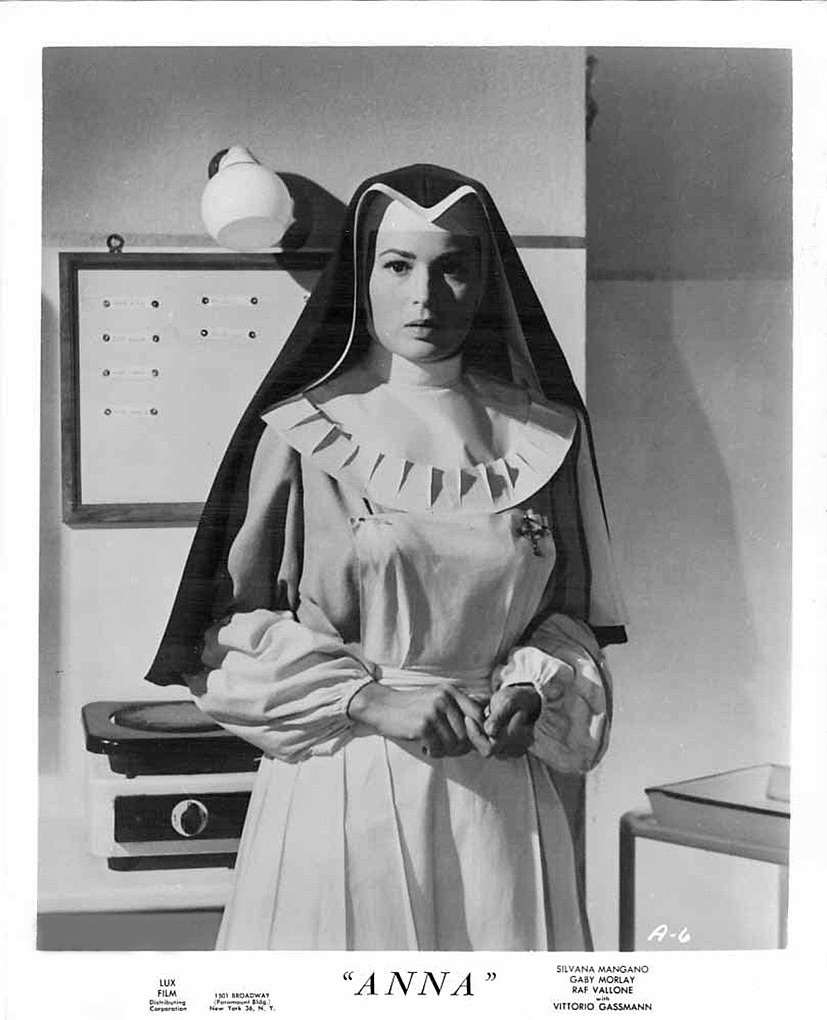

When the film opens Anna is a novice nun working as a nurse in training at a hospital where her professionalism and kindness are admired by the staff and patients. Dr. Ferri (Jacques Dumesnil), the head doctor, even says to her at one point, “I’d love it if you made a mistake just once in a while.” Of course, he doesn’t know about Anna’s past, a secret that is only known by the Mother Superior (Gaby Morlay), who manages the nursing staff.

Much of the first third of Anna shows her benevolent and saint-like presence among the patients as she goes about her daily rounds, tending to an injured athlete, a gruff army officer who may have been a fascist, a hypochondriac diva, and a little boy who is left alone after his mother dies during surgery (the scene is rather startling since we see a spray of blood hit the operating doctor’s gown during the procedure). Later, when a man who was seriously injured in a car accident is brought in after hours, Anna is shocked and rushes to retrieve Dr. Ferri from an opera performance in the hopes of saving the victim’s life. The patient in question is Andrea (Raf Vallone), a wealthy country farmer, whom Anna was once engaged to marry, and the film flashes back to this chapter in her life.

This middle section of Anna is the most entertaining for its lurid and over-the-top melodramatics which almost descend into film noir territory. Set in a swanky nightclub, Anna is the star entertainment, performing three musical numbers per night. The job is more glamorous than it looks and doesn’t pay that well since Anna still shares a tiny apartment with her sister Luisa (played by Patrizia Mangano, Silvana’s real-life sister). Anna not only has to maneuver around her boss’s attempts to offer her up as a companion for well-heeled male customers but she is also trying to end her relationship with Vittorio (Vittorio Gassman), a sleazy bartender who has a strong hold over her. Unfortunately, their mutual sexual attraction is like a sickness that can’t be cured. (Anna and Vittorio’s scenes together are tame by today’s standards but their chemistry together is undeniable and both are at the height of their physical beauty).

Anna’s life is thrown into turmoil once Andrea enters the film and pursues her romantically. As much as she longs to become his financee, she feels her sordid past makes her unworthy and tells him, “My destiny isn’t to become a wife.” Yet he persists and she eventually decides to leave the nightclub and marry Andrea. On the eve of her wedding, however, Vittorio shows up at Andrea’s country estate and threatens to reveal the truth about his torrid relationship with Anna. It all ends in a violent fight, a fatal shooting and Andrea being accused of the crime. But it also marks the third and final chapter of Anna’s transition from showgirl to nun.

Unlike other melodramas where the female heroines finally find romance and happiness after suffering nobly, Lattuada’s film upends audience expectations by concluding with a different fate for Anna through a decision of her own making. The fact that she finally redeems herself must have been pleasing for the Italian censors after being subjected to a steamy and morally objectionable midsection but the nightclub sequences are still the most memorable. Mangano’s performance of the popular novelty number “El Negro Zumbon,” where she is flanked by two black dancers with macaras is playful, mischievous and sexy while her melancholy performance of a ballad is depicted as an exercise in mood lighting where the orchestra appears as a silhouetted background (Both songs were dubbed by Mammola Sandon, who went by the stage name of Flo Sandon’s). If you look quick, you also might glimpse Sophia Loren in an uncredited bit in the nightclub scene (the actress would go on to marry co-producer Carlo Ponti in 1957. It was considered an illegal marriage and was annulled in 1962 but they remarried legally in 1966).

If Bitter Rice was the film that truly launched the careers of Mangano, Vallone and Gassman, then Anna was the movie that established them as stars on the rise. Mangano would go on to win acting awards for her work in Carlo Lizzani’s Il Processo di Verona aka The Verona Trial (1963) and the short story fantasy compilation Le Streghe aka The Witches (1967) but she would experience an even greater career resurgence in the late sixties/early seventies through the work of Pier Paolo Pasolini [Oedipus Rex (1967), Teorema (1968), The Decameron (1971)] and Luchino Visconti [Death in Venice (1971), Ludwig (1973), Conversation Piece (1974).

Both Vallone and Gassman would also reach greater career peaks and international fame. Vallone was paired opposite Simone Signoret in Marcel Carne’s noir drama Therese Raquin aka The Adultress (1953) and co-starred with Sophia Loren in Two Women (1960) before branching out into big budget, international productions like El Cid (1961), A View from the Bridge (1962), Phaedra (1962) and The Cardinal (1963), directed by Otto Preminger. Gassman, on the other hand, became Italy’s most famous leading man next to Marcello Mastroianni, although he was admired even more for his stage work in Italy than his films. Despite a brief marriage to Shelley Winters and an unsuccessful stint in Hollywood (1952-54), Gassman became an accomplished comedian in classic satires like Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), Dino Risi’s Il Sorpasso (1962) and Ettore Scola’s The Devil in Love (1966). He also proved he was a gifted dramatic actor, winning accolades for performances in Profumo di Donna aka Scent of a Woman (1974) – he won the Best Actor award at Cannes and the Golden Globes – plus the historical epic The Desert of the Tartars (1976) and The Family (1987) among many others.

Still, Alberto Lattuada is probably the one who experienced the most immediate success following the release of Anna. The box office hit allowed him to mostly pick and choose his own film projects. His next film, The Overcoat (1952), an adaptation of Nikolay Gogol’s short story, is often listed among his greatest achievements along with the black comedy Mafioso (1962). Yet, he would continue to surprise audiences and critics with his unexpected swings from one genre to another such as I Dolci Inganni aka Sweet Deceptions (1960), a coming of age romantic drama featuring Catherine Spaak in her first starring role or the oddball spy spoof Matchless (1967).

In August 2026 Lattuada will be honored with a retrospective of his work at the Locarno Film Festival in Italy. The program notes for the tribute state, “Lattuada often appeared eccentric and unclassifiable but came up with a kind of cinema that was extremely modern, and simultaneously both high- and low-brow. As an intellectual, architect, critic and photographer in his formative years, Lattuada remained true to the Modernism of the vibrant cultural hub of Milan and was a constantly percipient observer, often ahead of his time in picking up on the grand societal changes of the second half of the 20th century.”

Anna is not currently available on any format in the U.S. and is unlikely to become a future release for the Criterion Collection or other prestige distributors of international cinema on Blu-ray due to the film’s lack of critical acclaim or artistic merit. But it is certainly a cultural milestone of some kind and historically important for its main players but also Lattuada’s film crew which includes music composer Nino Rota and cinematographer Otello Martelli, who filmed landmark movies for Roberto Rossellini [Paisan (1946), Stromboli (1950)] and Federico Fellini [I Vitelloni (1953), La Strada (1954), La Dolce Vita (1960)]. For those who are interested, a subpar but viewable copy of Anna (without English subtitles) can be streamed on Youtube.

Other links of interest:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2005/jul/05/guardianobituaries.artsobituaries1

https://italiancinemaarttoday.blogspot.com/2015/04/spotlight-on-cinema-icon-silvana-mangano.html

http://www.poro.it/rafvallone/rafinglese.htm

Acidentaly I saw this just 3 days ago and like it a lot (8/10). Melodramatic for sure, but so Italian and beautiful done, one just got to like it. And Lattuada has always delievered the goods,