People tend to forgive artistic geniuses for their human imperfections when their talent is so monumental – this could also apply to any super-celebrity with landmark achievements in any field from sports to politics to music – but at a certain point, there is a limit to what society will tolerate. The protagonist of Baal, a 1970 film adaptation of the Bertolt Brecht play, is the embodiment of this. A former office clerk turned itinerant poet and musician, Baal’s work propels him to the level of a literary icon, beloved by the intelligentsia and the common man. He could care less because he hates everything, including the society that helped shape his talent. More importantly, he hates himself and that self-destructive urge informs his every act, making him one of the most nihilistic and anti-social characters even conceived for the stage or screen.

When you consider Brecht’s original conception of Baal, there is no way such a work could ever achieve mainstream commercial success but that is also why the play and its various adaptations continue to fascinate its interpreters. And the central dilemma may be unsolvable: how can an anarchic but brilliant talent like Baal coexist and flourish in a world with set rules and values? Since the poet is incapable of compromise or restraint, this film adaptation, scripted and directed by Volker Schlondorff, becomes a polarizing but compelling portrait of hero worship, social hypocrisy and creative burnout that makes no apologies for its leading anti-hero. The director retains Brecht’s dispassionate approach to his protagonist allowing the viewer to contemplate the contrast between an artist who could create beautiful, life-affirming poetry and, at the same time, exist as a drunken, whoring, amoral mess of a human being.

The film, which is episodic in nature and marked by numbered chapters, opens with Baal strutting along a country road, smoking a cigarette and spouting verse as a plaintive folk ballad underscores the scene (the music score is by Klaus Doldinger). In short order, Baal attends a fancy dinner party in his honor where he insults his host and guests while making a pig of himself. He humiliates Emilie (Miriam Spoerri), the wife of an admirer, at a local tavern in front of the amused patrons. He seduces Johanna (Irmgard Paulis), the wife of a friend, and discards her, causing her to commit suicide by drowning. Baal also crosses paths with Ekart (Sigi Graue), a fellow poet, who he betrays and eventually murders, two high school girls (for a sexual tryst), Sophie (Margarethe von Trotta), an actress who gives up her career for him, and a group of intoxicated hospital patients. He eventually ends up with a group of woodcutters but his life of debauchery catches up with him and he crawls off to die alone in the forest.

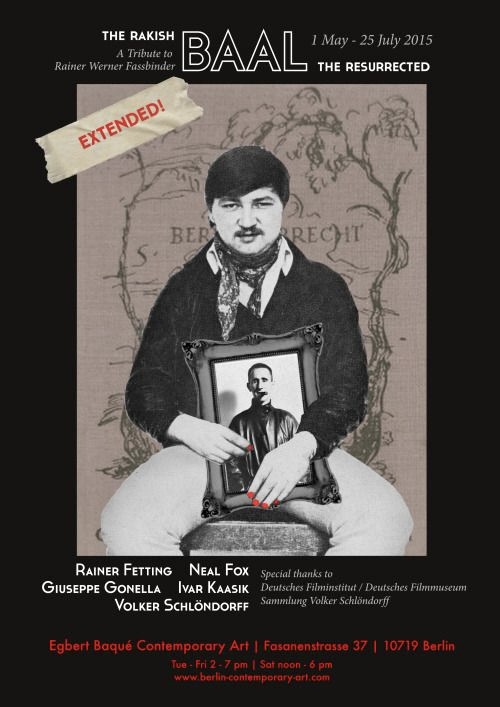

Schlondorff concocts a world where the public is besotted with Baal’s poetry and every woman succumbs to his sexual magnetism but the poet is quite a different anti-hero from more iconic examples in cinema like Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire or Paul Newman in Hud. Unlike those seductive examples of rebelliousness and male beauty, Baal has an acne-scarred face, a bulky physique, and is constantly drunk, sweating, dirty and oblivious to his own stench. And it is hard to imagine a better actor to play him than Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who had just directed his first feature film, Love is Colder Than Death (1969). In some ways, Fassbinder’s own off screen behavior mirrors that of Baal with his many vices and excessive behavior. Other similarities include the way he sometimes humiliated, bullied, seduced and discarded admirers and colleagues who were in awe of his talent.

It is also interesting to note that Schlondorff hired several actors who had worked with Fassbinder for this production. In minor roles, you can spot Hannah Schygulla as a barmaid, Irm Hermann as the outraged mother of a young girl seduced by Baal, Harry Baer as a dinner guest and Gunther Kaufmann as a tavern customer. Kaufmann and Fassbinder would become lovers during the making of this film and the actor would appear in such subsequent Fassbinder productions as Gods of the Plague (1970), The Niklashausen Journey (1970), Rio das Mortes (1971), Pioneers in Ingolstadt (1971) and would play the lead in Whity (1971).

Schlondorff and actress Margarethe von Trotta would also become a couple after Baal with the latter becoming one of Germany’s most important female directors, lauded for such feminist works as The Second Awakening of Christa Klages (1978), Sisters, or the Balance of Happiness (1979) and Marianne and Juliane (1981).

Baal was the first full length play written by Bertold Brecht in 1918 when he was still a student at the University of Munich but it wasn’t performed publicly for several years. “Named for a pagan god of fertility and thunder,” according to Dennis Lim in an article for The Criterion Collection, “Baal had a real-life model, a charismatic ne’er-do-well in the playwright’s Bavarian hometown of Augsburg whose hedonistic exploits were said to have led to a lonely death in the Black Forest. Although he wrote Baal nearly two decades before formalizing his doctrine of alienation, the young Brecht was already at pains to keep spectators at a distance, mindful that they not be granted “an invitation to feel sympathetically, to fuse with the hero,” as he put it. He need not have feared: within a week of its initial staging, in Leipzig in 1923, the city council had shut down the production and censured the director.”

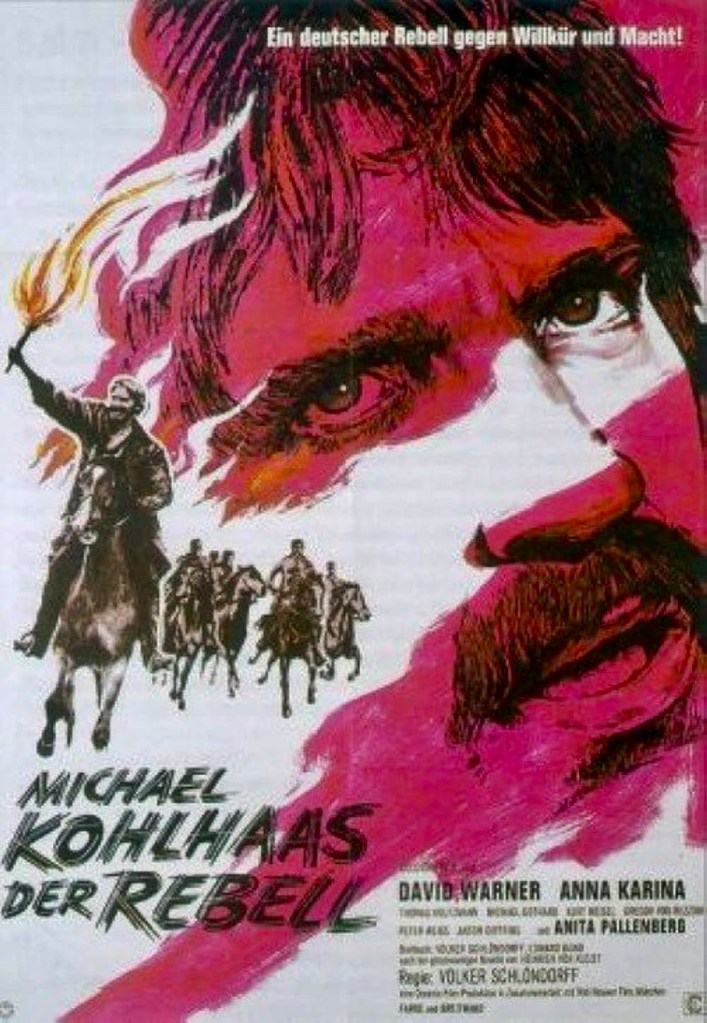

Baal was Schlondorff’s fourth feature film and was made for German television on a low budget using 16mm film while experimenting with various cinematic techniques such as the remarkable hand-held opening shot of Baal walking through a rural landscape as the camera circles him continuously. The director had recently completed the medieval epic Michael Kohlhaas – Fer Rebell aka Man on Horseback (1969), based on Heinrich von Kleist’s novel, but the movie was a major flop and Schlondorff wasn’t sure he wanted to make another movie. He had launched his career with Young Torless (1966), an adaptation of Robert Musil’s 1906 novel, which was critically acclaimed and nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. His follow-up feature, A Degree of Murder (1967) starring Anita Pallenberg, hadn’t generated the same interest and Michael Kohlhaas was another creative misstep.

At this point, Schlondorff remarked in an interview, “I didn’t see how one could reject the commercial system yet at the same time work within that system. That’s when I came across this first play by Brecht called Baal which was a portrait of a man who rejects society’s rules to the point of self destruction.” The film might have been a major artistic comeback for Schlondorff but, after its television premiere, the movie was denied future screenings due to complaints by Helene Weigel, Brecht’s widow, who despised this 1970 adaptation. Schlondorff would soldier on, working on modestly budgeted TV and film productions but it wasn’t until 1979 that he achieved international success for his film version of Gunter Grass’s novel The Tin Drum.

Still, Schlondorff was always proud of Baal and recalled in an interview with Peter Becker of The Criterion Collection the reasons he wanted to make it. “When I first came upon this work, it seemed to express so much of the feeling we had in ’68, ’69, and it had been written fifty years earlier, unbelievably, right after the First World War. Like to throw all civilization overboard, looking for the instincts, for the original passion of our genes, when we were still closer to Mother Nature. And here it was expressed, coming out of the First World War, like the German painters Otto Dix and George Grosz, indeed, in a very, let’s say, antibourgeois way. Not only the morals but the aesthetics were so antibourgeois. And then as I was looking for the character to play this part, I came upon Fassbinder, who was still doing theater. And it seemed to, again, be such a correspondence. We shot this fifty-year-old piece of literature as if it were social reportage, contemporary to us.”

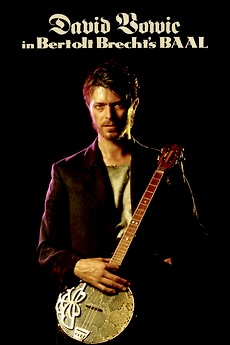

Baal remained largely unseen by anyone until 2014 when a new digital restoration of the film was unveiled at the Berlin Film Festival. It is now acknowledged as one of Schlondorff’s most successful adaptations of a literary work utilizing most of Brecht’s original text. The film’s experimental mixture of naturalism and the theatrical is surprisingly effective and most critics agree that it is superior to the 1982 version made by Alan Clarke for British television and starring David Bowie.

Schlondorff’s adaptation is also significant as one of the movies that marked the early beginnings of the New German cinema movement, which unofficially began with Alexander Kluge’s trailblazing drama Yesterday Girl in 1966. Other early examples include Werner Herzog (Signs of Life, 1969), Thomas Schamoni (A Big Grey-Blue Bird, 1970), Rudolf Thome (Detektive, 1969) and Fassbinder’s Love is Colder Than Death (1970). After 1970, the floodgates opened and we saw the rise of other prodigious talents like Hans W. Geissendorfer (Jonathan, 1970), Peter Lilienthal (Malatesta, 1970), and Wim Wenders (The Goalkeeper’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (1972).

New German cinema reached a creative peak in the mid-seventies with such masterworks as Herzog’s Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972), Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), Wender’s Alice in the Cities (1974), and the Schlondorff-von Trotta collaboration, The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975) but Baal was certainly one of the sparks that started the fire.

Film critic Michael Barrett of PopMatters said this about Baal, which I think captures the movie’s radical appeal: “What we have is an unpleasant portrait in which the protagonist behaves monstrously and callously towards everyone for 90 minutes — we wouldn’t wish it longer — while spouting poetry in a near-constant state of inebriation. While functioning as a portrait of the tortured and torturing artist pushed to the extreme of ironic parody and subversion, the film is also a rather breathtaking synthesis of talents, shot with self-conscious beauty in long takes, often with vaseline smeared around the edges of the lens to provide a mock-romantic warping and distancing.”

Anyone interested in experiencing this early work by Schlondorff should definitely check out the Blu-ray edition released by The Criterion Collection in March 2018. The special features include interviews with the director from 1973 and 2015, an interview with actor/filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta, a conversation between playwright Jonathan Marc Sherman and actor Ethan Hawke on the play and adaptation and other extras.

Other links of interest:

https://www.umass.edu/defa/people/591/