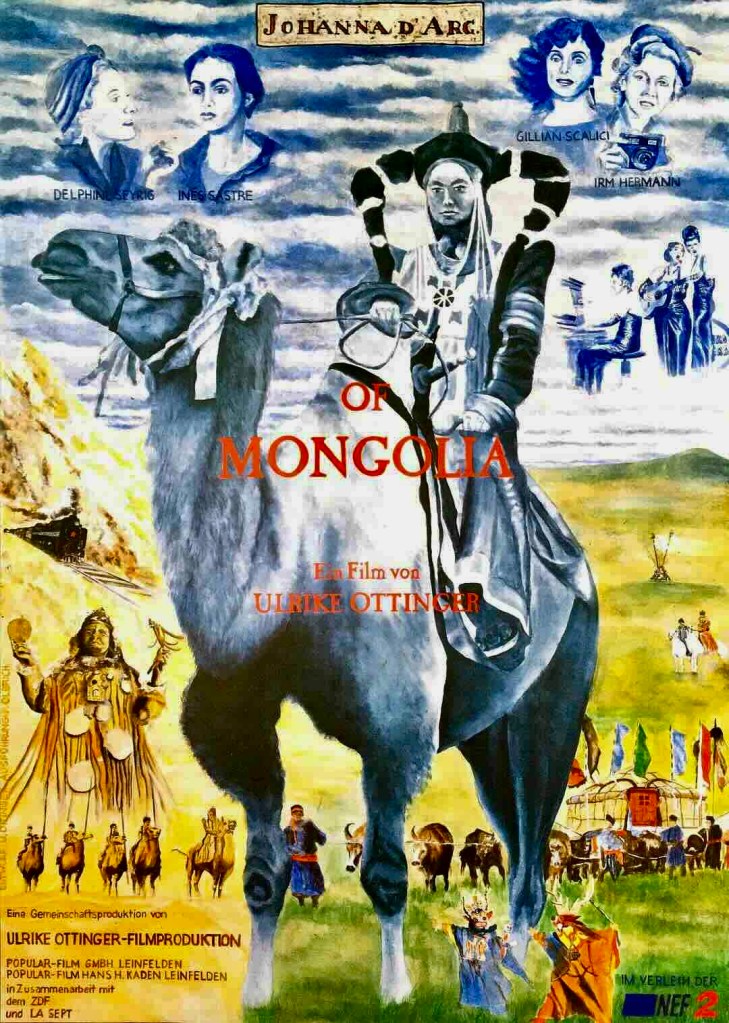

Movies that take place on trains constitute a film genre of their own and there have been plenty of great ones over the years – The General (1926), The Lady Vanishes (1938), The Narrow Margin (1952), Snowpiercer (2013) – but I can safely say that Johanna D’Arc of Mongolia (English title: Joan of Arc of Mongolia, 1989), directed by Ulrike Ottinger, is the most unusual one ever made. Although it embraces the idea that travel can be a life-changing experience for everyone, Ottinger puts her own personal spin on this by addressing ideas about gender, history, personal empowerment and cultural traditions through a smash-up of popular genres. These include musical theater, campy soap operas, widescreen epics and ethnographic documentaries. It might sound like either a complete goof or pretentious nonsense (some detractors claim both) but it works as a one-of-a-kind hybrid, informed by Ottinger’s insights into human behavior and her own directorial eccentricities.

Clocking in at two hours and forty-five minutes, Joan of Arc of Mongolia can be seen as a marriage between the surreal and the real with the first hour taking place within a highly stylized train set before disembarking to explore life on the wild plains of Mongolia. Among the featured passengers are Delphine Seyrig (in her final feature film) as Lady Windermere, a high society ethnologist and expert on Mongolian culture, Ms. Mueller-Vohwinkel (Irm Hermann), a German schoolteacher, Fanny Ziegfeld (Gillian Scalici), a Broadway musical star, Giovanna (Ines Sastre), a young traveler with her backpack, Mickey Katz (Peter Kern), a Yiddish theater star with a prodigious appetite for gourmet meals, and the Kalinka Sisters (portrayed by Jacinta, Else Nabu and Sevimbike Elibay), a Klezmer musical trio that performs standards like “Bei Mir Bistu Shein” and “Midnight in Moscow.” (Both Irm Hermann and Peter Kern are best known for their collaborations with director Werner Rainer Fassbinder on several of his films).

The absurdist aspects of this first section are accented by the flat theatrical facades of the train stations they stop at along the way featuring cartoonish vendors and musical performers on the platforms. Even the interiors of the Trans-Siberian Express are suggestive of an alternate reality such as Lady Windermere’s lavish private saloon with its wood paneled walls decorated with paintings, antiques and art objects. Ottinger also has fun with the main male character on board – Katz, whose flamboyant behavior includes performing an impromptu song and dance rendition of the Al Jolson standard, “Toot Toot Tootsie (Goo’ Bye!),” and ordering an elaborate feast for himself that includes a roasted swan in full plumage and blossoming waterlilies in aspic.

It is also during the opening train journey that Lady Windermere takes a personal interest in Giovanna and invites her to share her cabin, where their mentor-pupil relationship is clearly meant to be something more intimate. At the same time, the German schoolteacher and the Broadway star also become companions with the former representing the typical German Bourgeois stereotype (judgmental, repressed, overly cautious) and the latter as an open and adventurous free spirit. This dynamic will change and mutate into something else in the second half of Joan of Arc of Mongolia when Katz departs from the train to perform at an opera house in Harbin, China and the women continue on to a more remote region of Asia.

The transition from fantasy to documentary-like realism occurs when the train is forced to stop near the steppes of Mongolia and a group of warrior women, led by Princess Ulan Iga (Xu Re Huar), escort the women from the train to their village as hostages, although they are actually treated like more like privileged guests. For the remainder of their trip, the European women are witness to and participate in the Mongol tribal rituals and customs such as hunting animals for food and celebrating communal harmony through dance, music and role playing. Through it all, Lady Windermere acts as the learned interpreter/translator for her group while Princess Ulan Iga sets the agenda for her guests. The result is an absorbing ethnographic portrait of Mongolian tribal women which successfully integrates the arrival of these fictional European outsiders into a believable vision of cultural exchange between two radically different societies.

While Joan of Arc of Mongolia is by no means a mainstream commercial film, it is remarkably accessible if you give in to its stylized look and tone which slowly becomes hypnotic in the second half with its outdoor widescreen cinematography of Inner Mongolia (Ottinger also served as cinematographer). What may look like a stunt or a joke on first impressions is actually just a hook to bring the viewer into an alternate point of view. Ottinger is not really interested in a traditional plot or detailed character development or creating dramatic situations for engagement. She wants to experience the interaction between the two subcultures of women by simply bringing them together and watching them learn from each other. What we are actually watching is a group of professional actresses being exposed to Mongolian culture by genuine tribal nomads, not actresses. And it is not staged or scripted.

In one particularly hard-to-watch sequence a goat is slaughtered on camera by a tribal butcher while a chorus of colorfully dressed village women accompany the ritual with a song. We watch in real time as the goat is carved into different cuts of meat, its fur removed for clothing and internal organs and blood are saved for other uses. Everything is utilzed, nothing is wasted. While a number of other Mongol customs are depicted in a candid, unadorned manner, Ottinger occasionally resorts to magic realism in scenes such as one where the grassy plains of the steppes split open in an earthquake and two smoking mounds emerge with Ms. Mueller-Vohwinkel standing triumphant on one and her spiritual tribal mentor on the other. The use of the Kalinka Sisters as a kind of Greek chorus is also played for laughs as they continually pop up among the tribal women dressed in skin tight outfits and sporting matching hairdos. The unlikely combination of fantasy and documentary doesn’t sound like it should work at all but Ottinger’s unconventional directing style turns an avant-garde concept into something completely plausible.

Ottinger visited Inner Mongolia (where the movie was filmed) three times before returning to shoot Joan of Arc of Mongolia over a three and half month period. She took along her workbooks, which included storyboards, sketches and research materials, to show the tribal people the type of film she wanted to make with them. ‘This was so unusual for them because they were forbidden to speak Mongolian,” the director said in an article by Amy Sherlock for Frieze.com. [The region is part of the People’s Republic of China so the Mongolians must adhere to Chinese government policies in all matters]. “Yet, there was I, coming from outside, saying: “I’m interested in your culture and not in Chinese culture.” I never asked inquisitorial questions; I just showed them my big workbooks and, immediately, we’d have a discussion: “Oh, my mother had this. We still have this, but now we are doing it differently.”’

Working with professional actors and non-actors in Mongolia was part of a discovery process in which the cast, crew and director all learned things about each other’s culture, which was built-in to the movie’s narrative. Ottinger said in a Q&A session for Metrograph.com, “This is also a combination I like very much – to have great actors, famous actors, really very professional actors, and to then have them work together with people who, maybe for just one role, are perfect. It provokes a kind of reaction, it changes professional actors and it changes also the non-professionals; there’s kind of inter-dialogue or inter-reaction. So all these hybrid situations are very interesting, because you can find out something, you can play with it.”

A perfect example of this is the scene where the German schoolteacher is doing her laundry by a river. “Actress Irm Hermann was washing her clothes,” said Ottinger, “and putting them to dry on a string. For Mongolians, this is absolutely forbidden, because putting fabric on a string is something you do as an offering for the gods. It was an unbelievable misunderstanding but was quickly solved and became a comic scene.”

Joan of Arc of Mongolia was well received by most movie critics such as Frieda Grafe of Suddeutsche Zeitung, who wrote, “The whole film is a twin structure, cut through by doubles, repetitions, similarities and endless reflections. The images have a crease, established by the stories…In this way the Mongolian world casts a reflecting light on western customs and habits and cinema recommends itself as the instrument of investigation and the agent of old and new myths.” Shelia Benson of The Los Angeles Times called the film, “a wickedly delightful look at the headlong collision of two cultures…Sophisticated, mysterious and deliriously beautiful,” while Caryn James of The New York Times wrote, The director is at her playful best in upsetting the clichés of strangers on a train…JOHANNA D’ARC turns into a travelogue. But few travelogues are this rich, ambitious and unusual.”

Not all film reviewers, however, were enamored of Ottinger’s film such as Tony Rayns of TimeOut who wrote, “The assumptions about western and eastern cultures on which this rests are every bit as repulsive as they sound, and don’t stand up to a moment’s thought; but the really nauseating thing about the movie is its phony reverence for Mongolian traditions, seen as a matriarchal web of ethnic ceremonies and unfathomable secrets. Shameless.”

Still, the negative reviews were minor in comparison to the positive ones and I particularly like Richard Brody’s assessment of Joan of Arc of Mongolia in The New Yorker: “Style is a crucial part of personality, of personhood, of character – but “Johanna d’Arc” suggests that, like personal identity itself, it doesn’t emerge in isolation but is informed by culture, beliefs, heritage, landscape, a grand social realm that each person involuntarily represents and transforms. Ottinger seeks, through style, the deep background from which it arises, and finds a superb, simple cinematic correlate for that idea. For all its outwardly probing observation and decorative delights, the movie concludes with an abstract touch that’s as breathtaking as any of its sights and sounds.”

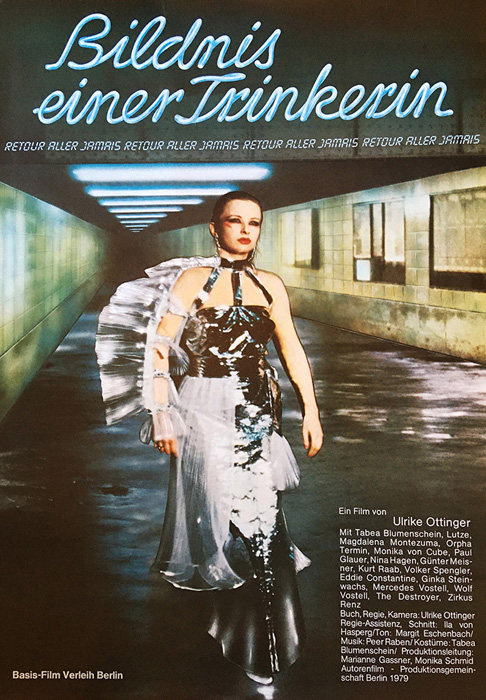

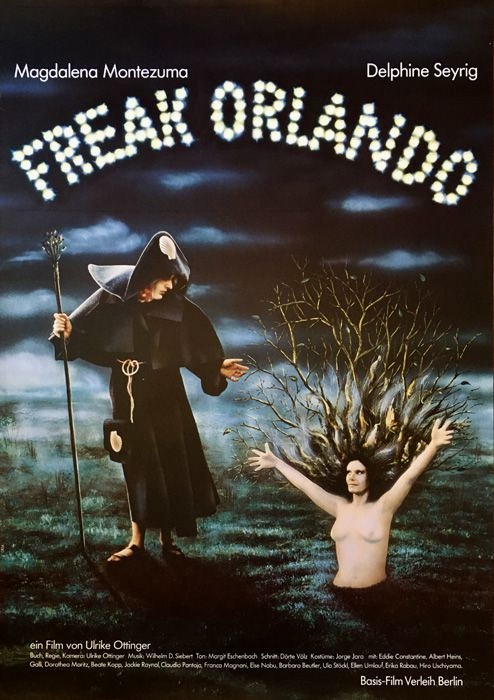

Joan of Arc of Mongolia did not have its U.S. premiere in New York City until May 1992 (3 years after its initial release) and it quickly vanished from sight. At that time Ottinger was not well known in America but in Germany she was considered one of the most important experimental filmmakers to emerge from the New German Cinema of the 1970s and was greatly admired by her peers. Today her reputation as a visionary LGBT filmmaker continues to grow but she originally got her start as a visual artist specializing in painting and photography. She eventually moved into filmmaking and opened a film club and art gallery in Konstanz, Germany in 1969. Her early films are marked by their absurdist and baroque presentations of rituals, fetishes and stereotypes as a means to address colonialism, queerness and feminist insubordination as in her 1978 fantasy, Madame X: An Absolute Ruler.

She is probably most famous for her ‘Berlin Trilogy’ of Ticket of No Return (1979) starring Tabea Blumenschein as a self-destructive woman who drinks her way through the bars of the city on her way to oblivion; Freak Orlando (1981) is a surreal history of civilization told in five chapters; Dorian Gray in the Mirror of the Yellow Press (1984) features famous sixties model Veruschka (von Lehndorff) as a bored playboy who is manipulated into a love affair by a newspaper and then tries to escape his tabloid existence.

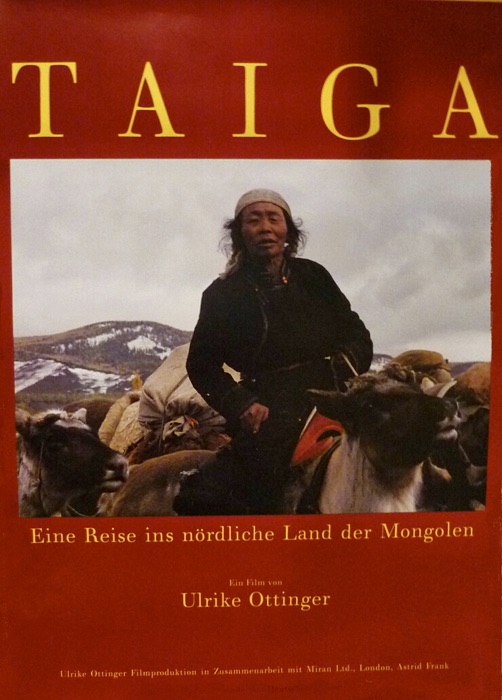

Ottinger has always been intrigued by the documentary format and in 1986 she made China. The Arts – The People, a four and a half hour cultural travelogue of China that covers everything from Sichuan opera to the Beijing Film Studio. It was the first of her anthropological studies and would eventually lead to Joan of Arc of Mongolia which combined fantasy with anthropology. Her experience of working in Mongolia on that movie inspired her to go back to that country a few years later and make Taiga (1992), an eight hour, 21-minute documentary portrait of the rituals and lifestyles of nomadic people in Northern Mongolia, particularly the Darkhad and the Sojon Urnjanghai nomads.

Joan of Arc of Mongolia was nominated for Best Film at the Berlin Film Festival but it has been difficult to see in the U.S. outside of film festivals or retrospective screenings at film archives and museums. I recently discovered, however, that the movie in its entirety is streaming on Youtube with English subtitles in a flawless digital restoration. Watch it now while you have the chance and stick around for the epilogue in which you find out what happened to the main female characters after they returned to their lives in Europe following their Mongolian adventure.

Other links of interest:

https://www.ulrikeottinger.com/en/biography

https://variety.com/2020/film/global/ulrike-ottinger-idfa-1234841476/

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Film/JoanOfArcOfMongolia