The 1960s might be seen as the decade that ushered in a significant number of game changing film movements such as the Czech New Wave, Cinema Verite and New German Cinema but the 1950s shouldn’t be overlooked for inspiring the birth of the Nouvelle Vague in France and the self-reflective ‘kitchen sink’ realism trend in England. One of the most influential but short lived film developments during this period was the Free Cinema movement, which flourished between 1956 and 1959 in the U.K.. It rejected the conservativism and class bound traditions of commercial filmmaking as well as the didactic approach to documentaries made famous by Scottish director John Griegson (Song of Ceylon [1934], Night Mail [1936]]. Instead, Free Cinema was dedicated to making personal films that expressed the opinion and artistic vision of their directors despite limited budgets and semi-amateur conditions (most of the movies were shot with a 16mm Bolex camera). Karel Reisz, Alain Tanner, Claude Goretta, Tony Richardson and Lindsay Anderson were among the leaders of the Free Cinema group but Anderson, in particular, created some of the movement’s most significant work, including Wakefield Express (1952), O Dreamland (1953), Thursday’s Children (1955) and Every Day Except Christmas (1957).

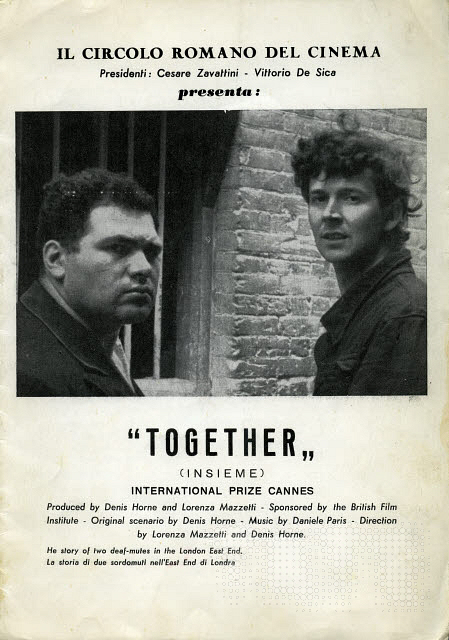

Poster for film ‘Together’ – 1956. Directed by Lorenza Mazzetti, starring Eduardo Paolozzi & Michael Andrews.

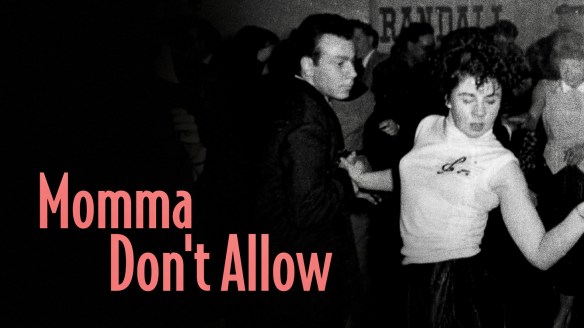

At first these directors were working independently of each other until they began to see shared similarities and approaches to their subject matter in the completed work. After a screening of Lorenza Mazzetti’s Together in 1955 – a tale of two deaf mutes in East London – these filmmakers formed a loose collective and issued a manifesto, signed by Mazzetti, Anderson, Reisz and Richardson, which was revealed at a public exhibition of three films – Together, Momma Don’t Allow (1956), directed by Reisz and Richardson, and Anderson’s O Dreamland.

The filmmakers stated, “These films were not made together; nor with the idea of showing them together. But when they came together, we felt they had an attitude in common. Implicit in this attitude is a belief in freedom, in the importance of people and in the significance of the everyday. As filmmakers we believe that no film can be too personal. The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments. Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim. An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude.”

The filmmakers stated, “These films were not made together; nor with the idea of showing them together. But when they came together, we felt they had an attitude in common. Implicit in this attitude is a belief in freedom, in the importance of people and in the significance of the everyday. As filmmakers we believe that no film can be too personal. The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments. Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim. An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude.”

The following is a sampling of Anderson’s best work in the movement, which began with the director’s pioneer effort in 1952, Wakefield Express.

Bearing the subtitle “The Portrait of a Newspaper,” this 33-minute short was commissioned by the publishers of the Wakefield Express to commemorate its 100th anniversary. Initially conceived as an educational featurette on the step-by-step production of a weekly newspaper, Lindsay Anderson transformed it into a much more personal portrait of life in the small towns within the West Riding district of Yorkshire, all of which were the focus of the Wakefield Express. The distinctive soundtrack, in fact, highlights songs from the Snapethorpe and Horbury Secondary Modern Schools and band music performed by the Horbury Victoria Prize Band.

Seen today, the film is a remarkable time capsule that shows the hustle and bustle of communities like Selby and Horbury, where certain social events and individuals are singled out for attention such as a rugby team practice (followed by an unexpected locker room sequence) or the unveiling of a WW2 memorial celebrated by a procession of singing/dancing schoolgirls. In another segment we meet Norman Fox, a bus driver and secretary of his town’s Pageant Committee, who also raises parakeets. Other examples include the odd detail of local women engaged in lawn bowling or the homecoming celebration of a channel swimmer champion. And whenever Anderson circles back to the inner workings of a newspaper staff, one can’t help but notice that the majority of employees are men and that they constantly smoke cigarettes or pipes while performing their duties. The smoke inside the offices is as indicative of the period as the pollution bellowing from the factory chimneys in the industrial towns of the region.

The program notes, which accompanied the public screening of Wakefield Express, best describe the film’s attributes: “There is nothing of the impartiality of the ‘general survey’ about the film’s approach. Its perceptive, humanist outlook brings enough concern to the communal activities to view them, in turn, with affection and irony, exasperation and respect.”

A photographer gives instructions to a group of schoolgirls for a portrait in Lindsay Anderson’s 1952 short, WAKEFIELD EXPRESS.

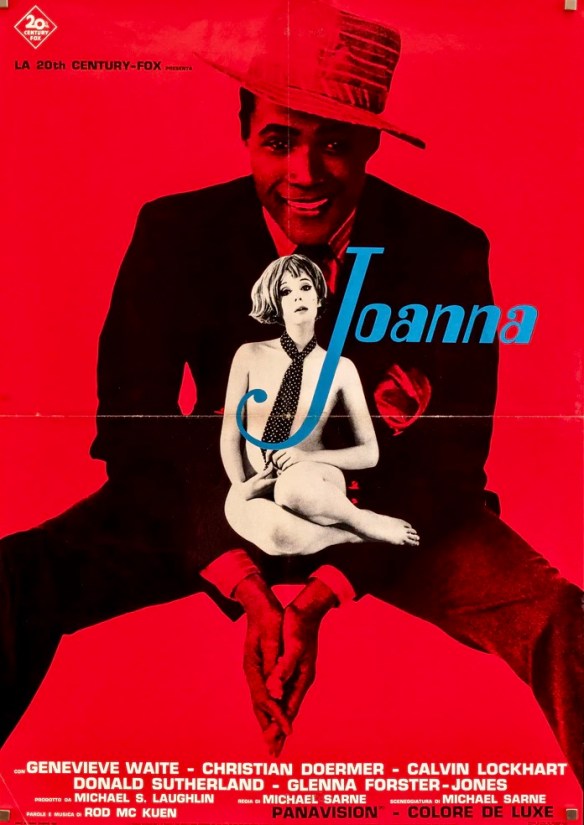

This was also the first time that Anderson worked with cinematographer Walter Lassally and editor/sound recordist John Fletcher, who would work on several other key films of the Free Cinema movement. Lassally, of course, became the go-to favorite for Greek director Michael Cacoyannis, winning an Oscar for his striking black-and-white camerawork on Zorba the Greek (1964). He also lensed some of Britain’s most iconic films of that era such as A Taste of Honey (1961), Tom Jones (1963) and Joanna (1968), Michael Sarne’s mod, swinging London musical-drama featuring songs by pop poet Rod McKuen.

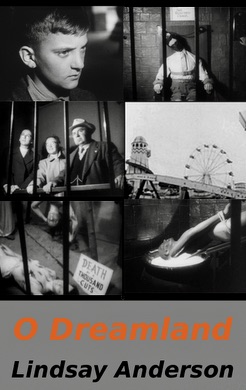

O Dreamland (1953)

An semi-experimental depiction of the famous amusement park in Margate, England known as Dreamland, this 13-minute short might be the most personal of Anderson’s Free Cinema projects. The film, which eschews tradition narration, utilizes the sounds of the midway, voices of carnival barkers, pop songs of the period such as “I Believe” by Frankie Laine and the ominous sound of crackling laughter from mechanical sideshow dummies.

One of the many mechanical dummies featured at the Dreamland amusement park as seen in Lindsay Anderson’s O DREAMLAND (1953).

There is something bleak and disturbing about the director’s portrait of this iconic tourist attraction, which opened in 1880 and survived until 2005, when it was officially closed. Although Dreamland was a destination for vacationing families and school kids, what we see on display is far removed from the innocent delights of something like Disneyland. Anderson takes us on a tour of a torture chamber where we see a dummy being dunked in boiling oil, a female figurine is hung upside down by two Arab men with knives and subjected to the “death of a thousand cuts,” and Joan of Arc is burned at the stake. All of this is accompanied by a vendor announcing, “This is history portrayed by life size working models. Your children will love it!”

A scene from Lindsay Anderson’s O DREAMLAND (1953), an impressionistic short film about a popular tourist attraction.

Along the way we also are subjected to scenes of forlorn zoo animals like a tiger pacing nervously in his cage or a trio of frightened monkeys, huddling together. Gravity-defying amusement park rides and arcade attractions like the ring toss or bingo vie for customers while the midway cafes serve up plates of beans, bangers and onions as typical fare. We also get a glimpse of the fair’s Wall of Death motorcycle exhibition and a replica of a familiar execution device – “See here the representation of the Electric Chair in which the atom spy Rosenberg was executed.”

The impressionistic montage is relentlessly vulgar and atmospheric in unsettling ways. Author/screenwriter/film critic Gavin Lambert, who was a great supporter of the Free Cinema movement, wrote, “Everything is ugly…It is almost too much. The nightmare is redeemed by the point of view, which, for all the unsparing candid camerawork and the harsh, inelegant photography, is emphatically humane. Pity, sadness, even poetry is infused into this drearily tawdry, aimlessly hungry world.”

When a vendor squeezes a female doll, it exposes its breasts in this scene from O DREAMLAND (1953), directed by Lindsay Anderson.

Thursday’s Children (1954)

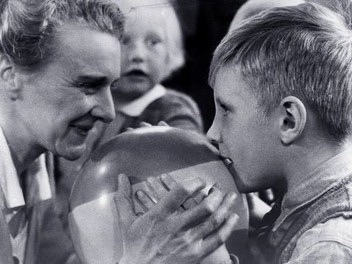

Much more compassionate and optimistic than Dreamland, this 21-minute featurette co-directed by Anderson and Guy Brenton is an inside look at the Royal School for the Deaf in Margate, England. Although it is narrated by Richard Burton, much of the film simply observes (without commentary) the efforts of a teacher to instruct deaf children on how to identify words with sounds and then to mimic them in their own voice. This is accomplished by having the children watch and sometimes touch the teacher’s lips as she sounds out a word.

The teacher is able to engage the small children by approaching all of the speech exercises as a game or as role playing such as having the kids pretend to be parents with a child of their own. In one surprising sequence the teacher uses the title character of Helen Bannerman’s popular children’s book, Little Black Sambo, as a way to illustrate the use and meaning of words like tiger, umbrella or tree within the context of the story. Of course, the title character of the Scottish author’s book is now considered controversial as a racist stereotype, but it is interesting (and typical of its era) to see it used as a teaching tool for the all-white deaf children.

A teacher of deaf children demonstrates sounding words out on a balloon in a scene from THURSDAY’S CHILDREN (1952).

The techniques used in Thursday’s Children are no longer employed in instructing the deaf as sign language is the favored approach in today’s world but Anderson and Brenton’s film is moving and memorable for scenes of the children interacting with each other and their expressive faces. The film went on to win the Oscar for Best Short Film of 1955 and earn critical raves. The Monthly Film Bulletin observed, “This short and unpretentious film achieves its object by the simplest possible means. There are no heroics or climactic structures of pathos…The secret is perhaps that the people who appear in the film – the bright, tired teachers and the puppy-like children, struggling unconsciously towards comprehension – are treated, and emerge, as human beings and individuals – an attitude not always common in British documentary.”

Some of the young students from the Royal School of the Deaf are featured in the 1952 short, THURSDAY’S CHILDREN, narrated by Richard Burton.

Every Day Except Christmas (1957)

Quite possibly Anderson’s finest short film and a key work of the Free Cinema movement, this 37-minute work is a fascinating and immersive portrait of London’s Covent Garden, the famous fruit and vegetable market that flourished in the city from around 1654 to 1974 when it became less of a food market and more of a hub for restaurants, pubs and shops.

The daily operation of such a massive enterprise begins appropriately enough at midnight as drivers and carriers via wagons, trucks, trains, planes and ships begin transporting their goods to the market – boxes of mushrooms from Sussex, oranges and lemons from England’s western ports, grapes from South Africa, etc. As the produce begins to arrive, market workers get busy unpacking and arranging the food stalls before the vendors arrive to sell their wares at the crack of dawn. And Lassally’s candid, free-roaming black and white cinematography and John Fletcher’s sound design captures this nocturnal community going about their business while capturing their conversations and interactions with each other. It is like taking a time machine back to 1957 when it was filmed.

A scene of a shopper buying flowers at the famous Covent Garden in London as seen in EVERY DAY EXCEPT CHRISTMAS (1957).

The market crowds usually reach their peak in the early morning hours and by noon the operation is dwindling down with any remaining or discarded items like flowers being picked over by second hand street vendors not unlike Eliza Doolittle’s flower seller in My Fair Lady. Some of the most evocative scenes highlight the faces and physical activity of the workers and the shoppers as well as quieter moments when some employees take time for a cup of tea and a sausage sandwich (an unappetizing close-up of a greasy banger being split in two, brushed with mustard and brown sauce, and served on crustless white bread).

A vendor hauls a wagonload of produce to the Covent Garden market in the 1957 short EVERY DAY EXCEPT CHRISTMAS.

“The film evokes what Anderson has called the ‘poetry of everyday life,’ wrote Christophe Dupin in his entry for BFI Screenonline, “and has the best lyrical qualities of the wartime films of Anderson’s idol Humphrey Jennings….The film makes perfect use of Free Cinema’s trademark features: virtuoso cinematography alternating highly poetic moments with candid camera shots, and an imaginative soundtrack using natural sounds, voices and added music. This time though, Anderson added a voice-over commentary [by Alun Owen] as a concession to the sponsor.”

A flower vendor at the Covent Garden in London advertises his religious beliefs with his wares in EVERY DAY EXCEPT CHRISTMAS (1957).

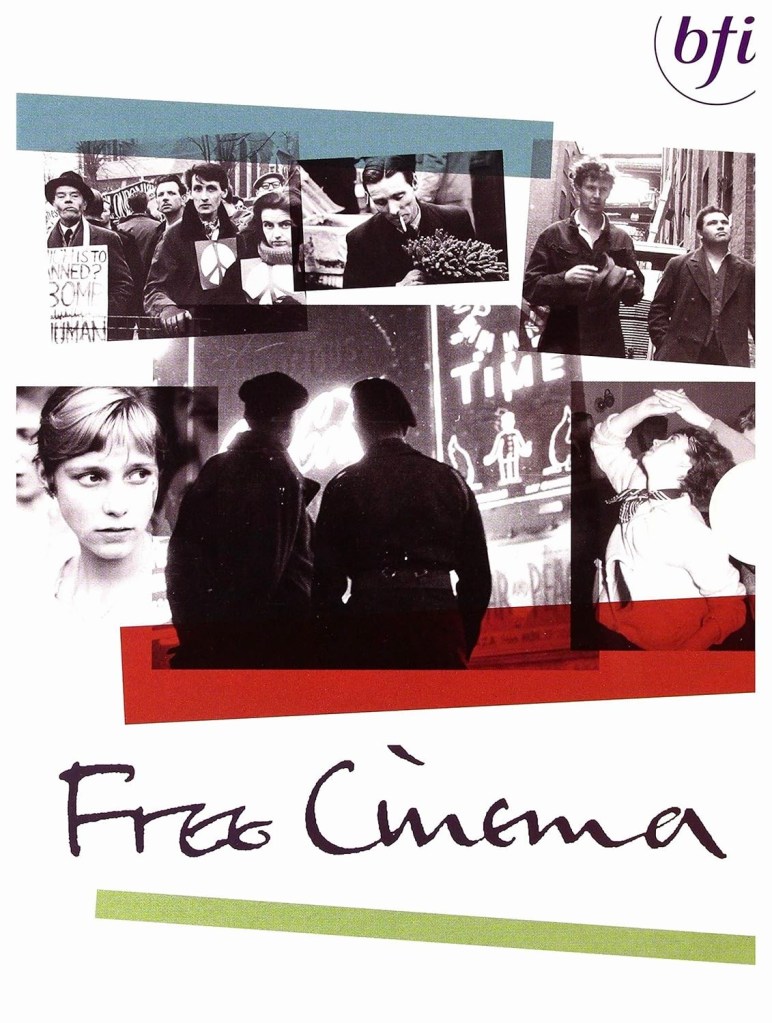

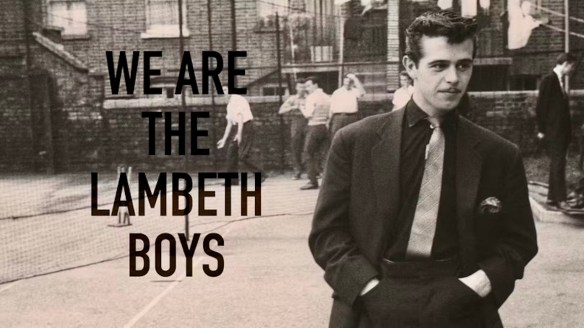

Other influential films of the Free Cinema movement include Momma Don’t Allow, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson’s portrait of a typical Saturday night at a jazz club in North London; Nice Time (2957), a look at Piccadilly Circus, the center of London’s entertainment scene by Claude Goretta and Alain Tanner; Refuge England (1959) from Robert Vas depicts the experiences of a Hungarian refugee as he wanders London from Waterloo to the West End; Karel Reisz’s We Are the Lambeth Boys (1959), in which teenagers at the Ashford House, a youth club in South London, express their frustrations and hopes for the future.

Most of these shorts (with the except of Anderson’s Thursday’s Children) and many others are featured on the 3-disc DVD collection Free Cinema, released by the BFI in March 2006 (It is still available from online sellers but you need an all-region DVD player to view it).

Other links of interest:

http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/592919/index.html

https://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue%201/ArticleGourdin-Sangouard.html