By the time Wim Wenders won the Palme d’Or at Cannes for Paris, Texas in 1984, he was well established as an internationally renowned director. He made his first big splash on the world stage in the early 1970s along with other New German Cinema directors (Werner Herzog, R.W. Fassbinder, etc.) with films such as The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (1972) and Alice in the Cities (1974). Wenders had also dabbled with non-fiction-like formats in early experimental shorts, music videos and the Cannes-focused TV documentary of various film directors in Chambre 666 (1982). Yet, it was Tokyo-Ga 1985), the feature length portrait he made directly after Paris, Texas, that really triggered Wenders’s interest in not just non-fiction filmmaking but in Japan cinema and culture, especially the works of Yasujiro Ozu.

In an interview with James Balmont of Anothermag.com, the director admitted that he was first exposed to films by Ozu in the mid-1970s. “I saw Tokyo Story, and I stayed for the next three shows [of Ozu’s films] that day until I stumbled out of the theatre late at night. I’d never seen anything that had so much shaken my world. It wasn’t necessarily the story, it was the way it was told – and the world I saw in there was a paradise of filmmaking. It was an utterly involving world: the world of the Japanese family. From then, I was clear. This was, from now, going to be my master.”

Later Wenders journeyed to Japan in 1977 to do further research on Ozu and fell in love with Tokyo. That trip inspired his return to the city in 1983 with a tiny crew to make a personal visual essay on Ozu’s approach to cinema. It had been twenty years since the director’s death when Wenders began shooting and he noticed the many changes that had occurred in Tokyo and Japan since Ozu’s passing. But even Ozu was well aware during his lifetime that change was constant and his movies, especially during the post-war era, addressed the slow deterioration of the Japanese family but also a loss of national identity. Tokyo-Ga certainly references this but it also works as an eccentric travelogue of Tokyo as seen by an outsider from Europe.

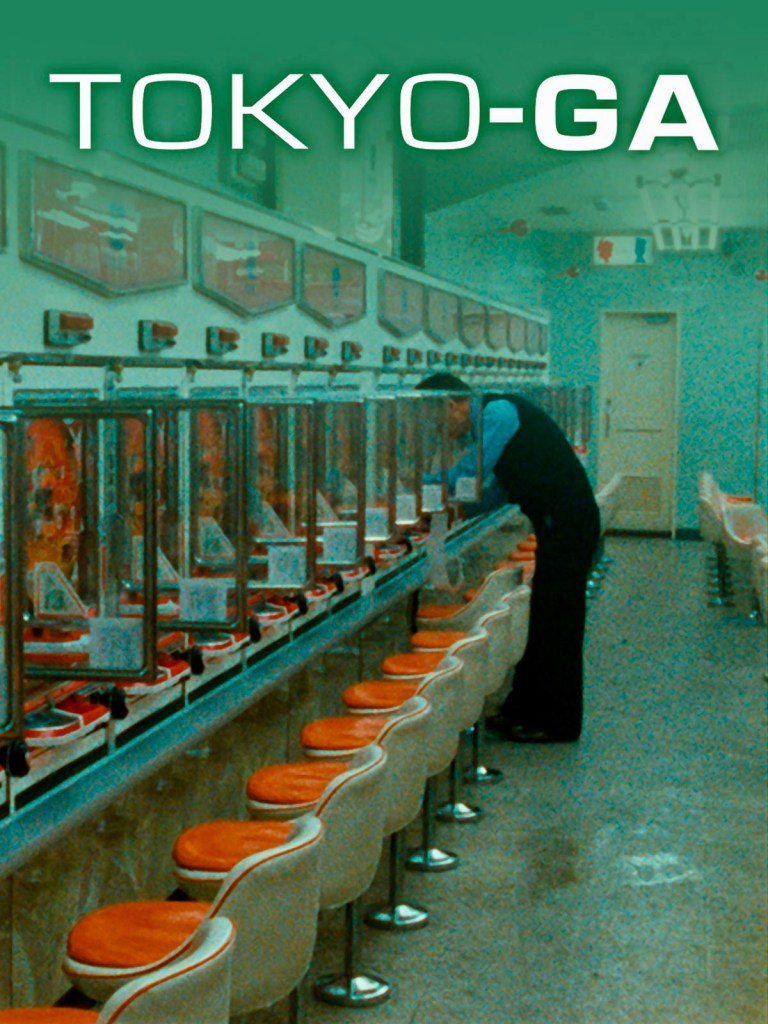

Tokyo-Ga opens with Wenders’s statement that he considers Ozu “a sacred treasure of cinema” but his 92-minute documentary is not a traditional portrait of the revered Japanese director. Instead, it is much more about the city, culture and a specific time period that had such an impact on Ozu’s cinema aesthetics. Yes, there are interviews with Chishu Rye, an actor who worked with Ozu on countless films starting in 1928, and Yuharu Atsuta, the director’s camera assistant and later his chief cinematographer for over 35 years. But much of Tokyo-Ga captures the unique appeal of Tokyo’s sights and sounds from Japanese businessmen picnicking in the park to the crowded pachinko parlors to the constant arrival and departure of trains, a recurring motif in Ozu’s movies.

At times Wenders’s portrait has the casualness of a home movie where people on the street look directly at the camera or interact with it (such as a rebellious toddler who sits on the ground and refuses to walk anymore). As a result, the director’s curiosity is rewarded with fascinating and rarely seen footage of Tokyo residents immersed in their daily lives, which includes an addiction to pachinko, the hyperactive arcade game featuring small silver balls in constant motion. There is something hypnotic and soothing about this unusual pastime that even affects Wenders’s voice-over narration – he sounds like he is reverting to a somnambulistic state.

Other highlights include a rock ‘n’ roll revival in the park where teenagers in black leather jackets and fifties retro gear dance to Elvis tunes but also American pop songs like The Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “The Peppermint Twist” by Joey Dee & the Starliters, and Blondie’s “Call Me.” Even more surprising are the golf driving ranges on the tops of Tokyo skyscrapers where city dwellers demonstrate their passion for the sport. But my favorite section focuses on the creation of the omnipresent food displays outside most Tokyo restaurants. Using real food such as shrimp, cucumbers or egg rolls, factory technicians assemble realistic looking meals and dishes after preserving the ingredients in a protective wax. The result is a visually appealing display of french fries, tempera dishes or sushi concoctions that look like the real thing – and are – but encased for eternity in a shellac-like coating.

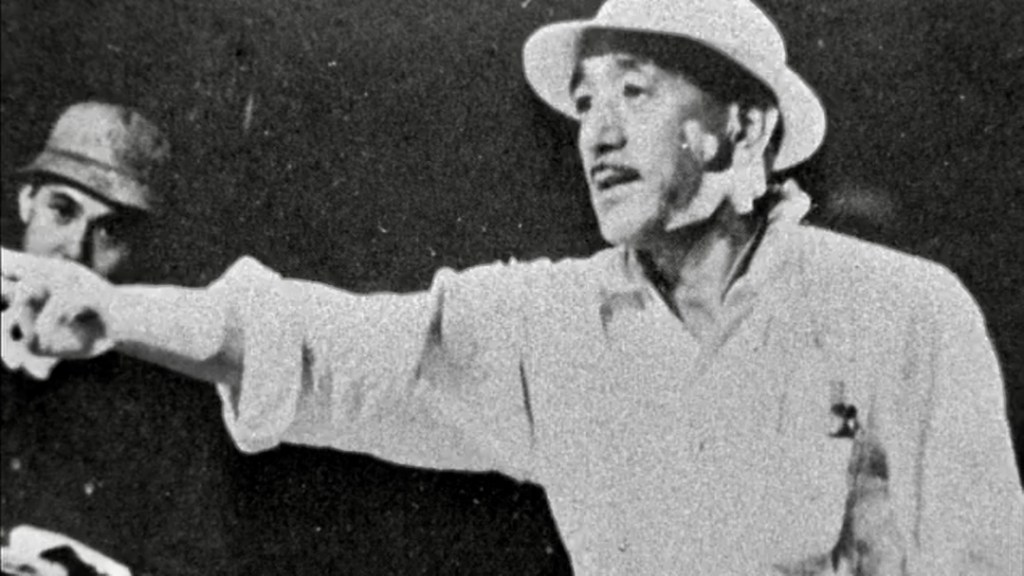

For Ozu aficionados, Tokyo-Ga is particularly rewarding thanks to candid observations from both Chishu Ryu and Yuharu Atsuta, who were close confidants and collaborators of the director. In a translation of Ryu’s words, Wenders says the actor, under Ozu’s direction, “learned to forget himself, to become an empty page…to never have a fixed notion about his work…and how to move in harmony with the master’s instructions.” What is interesting about Ryu is that he was always cast as someone much older than himself. When he was in his thirties, Ozu had him playing men in their sixties and his physical transformation was subtle but completely convincing. Despite giving such unforgettable performances in Ozu classics like Tokyo Story (1953), Tokyo Twilight (1957), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), Ryu was never nominated for acting awards in any Ozu movies. Strangely enough, it was in the films of other Japanese directors such as Hiroshi Inagaki’s Te o Tsunagu Kora (1948) and Noboru Nakamura’s Home Sweet Home (1951) where he received acting honors and acclaim in his own country.

The section with cinematographer Atsuta is equally revealing in regards to Ozu’s rigid approach to filming. The cameraman demonstrates Ozu’s preferred viewpoint for shooting a scene which was close to floor level. Shots were fixed and rarely, if ever, was panning an option for Atsuta. Wenders even uses the same box-like aspect ratio in this section, similar to what Ozu used for most of his movies. We also learn that Ozu was not one for complimenting his cast and crew for a job well done. The most positive thing he might say to a cast or crew member upon completing a scene might be – “That wasn’t so bad.”

Tokyo-Ga also includes some surprise appearances from two iconic film legends. Werner Herzog is glimpsed briefly pontificating about space travel from the observation deck of the Tokyo Tower and the elusive French writer/director Chris Marker is seen hiding behind a menu at a bar named after one of his films, La Jetee (1962), located in Shinjuku’s Golden Gai district of Tokyo.

You don’t have to be a fan of Ozu and his movies to enjoy Tokyo-Ga but a curiosity and interest in Tokyo and Japanese culture are required. For those who appreciate all those things, Wenders’s film should be a delightful viewing experience, even if Wenders’s hero worship of Ozu can border on hagiography. Even so, there are some unexpectedly moving scenes in Wenders’ portrait. One involves his visit with Ryu to the cemetery where Ozu is buried and Ryu washes the director’s headstone; the other is when Atsuta breaks down in tears recalling his sense of loss after Ozu’s death in 1963. Although he continued to work for other Japanese directors, the cinematographer admits that he only values the work he did for Ozu.

Tokyo-Ga had a limited theatrical release in the U.S. and was a difficult film to see for many years. In May 2006 The Criterion Collection released Ozu’s Late Spring on DVD and it included (on a separate disc) Wenders’s Tokyo-Ga as a supplement. This is still the best way to see this offbeat documentary. It would also make a great companion piece to Wenders’s Oscar-nominated feature (for Best International Film) Perfect Days (2023), which is set in contemporary Tokyo.

Other links of interest:

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/tokyo-wim-wenders-love-letter/

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/wim-wenders