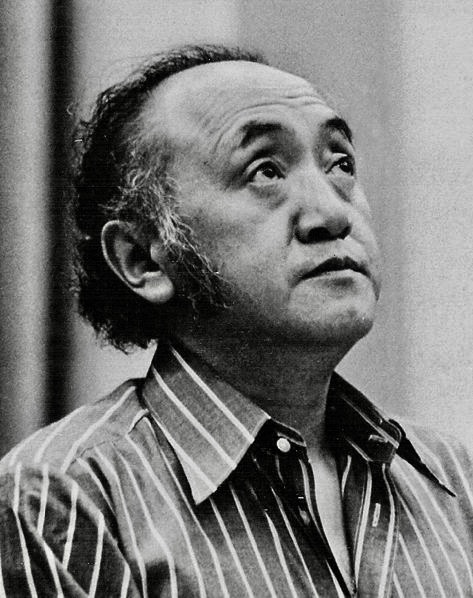

When Ishihara Shintaro died on February 1, 2022 at age 89, most obituaries focused on his career as a politician in Japan. He first served as a member of the House of Councillors (1968 to 1972) and then as a member of the House of Representatives (1972-1995) before becoming the Governor of Tokyo from 1999 to 2012. A controversial figure in his own country, Shintaro was famous for his ultra-nationalist stance on Japan and extreme right-wing views such as discriminating against Japanese-Koreans, the disabled, women, LGBT and other social minorities. He is now considered an early proponent of “hate speech” and often denied historical accounts of atrocities committed by the Japanese against the Chinese in the infamous Nanjing Massacre of 1937, which in Japan is the same as being a Holocaust denier. What is most surprising about Shintaro, however, is his earlier career as an author and highly successful screenwriter for movie studios like Nikkatsu, Daiei and Shochiku. His critically acclaimed first novella, Taiyo no Kisetsu (English title: Season of the Sun), was published in 1955 and he adapted it into a film for director Takumi Furukawa. It became a box office sensation and inspired several successors in a film movement that became known as the “Sun Tribe” (aka Taiyozoku) movies.

Season in the Sun was one of the first novels and movies to address the anger and rebelliousness of Japan’s postwar youth. The film, in particular, fleshes out its portrait of a younger generation rejecting the traditions and morals of their parents and Japanese society. Most of these troubled characters come from well-to-do families, have little interest in work, no responsibilities and spend their days indulging in partying, casual sex, brawling and hanging out at coastal resorts where they can run wild in the summer. In some ways, the attitudes of these Japanese teenagers were quite similar to the angst-ridden teenagers of Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and everything that screen icon James Dean represented to his generation.

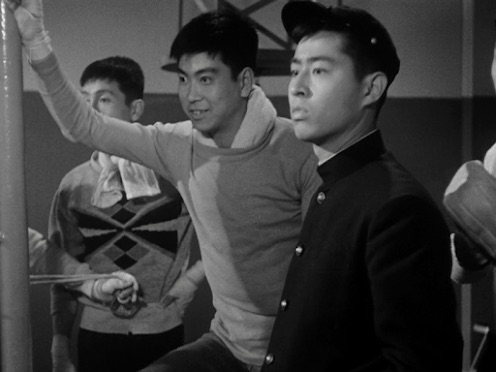

After an opening credit sequence that unfolds over what looks like a bubbling hot springs mud reservoir accompanied by Spanish flamenco music, the film introduces us to Tatsuya (Hiroyuki Nagato), a restless high school student, who joins his friends at the T-School Boxing Club. Even though he has no boxing experience, Tatsuya is anxious to prove himself in the ring and shows he has the makings of a good fighter despite being beaten. As he rises from novice to bantamweight champion, he becomes involved with Eiko (Yoko Minamida), a young woman from a privileged background like himself.

Tatsuya and Eiko feel a sexual spark from the start and soon realize that their nihilistic outlook binds them together. Neither profess to have any feelings for their parents nor do they have any use for love. When Tatsuya reveals he has “never been able to cry. I don’t know that feeling at all,” Eiko realizes she has found her soul mate.

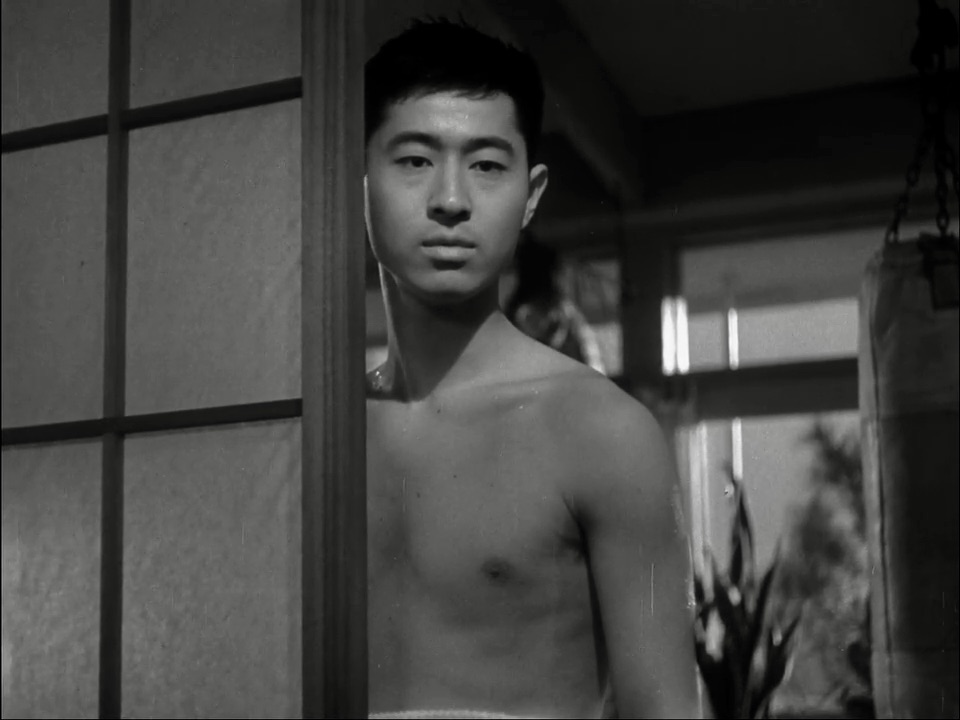

The Tatsuya-Eiko affair quickly escalates into a passionate physical relationship that ignites after Eiko visits Tatsuya at his home and they hole up in his bedroom. Turned on by his semi-nude body, Eiko urges him to “Show me how you hit the sand bag” and then watches with barely concerned lust as he pounds away ferociously. It ends with Tatsuya so aroused that he scoops Eiko off her feet and carries her off to bed like some caveman.

Despite the strong sexual attraction between them, Eiko and Tatsuya remain non-committal in their relationship and are free to date others. This free and easy attitude works for a while until Eiko shows up at a night club with his pals and he sees Eiko on a date with Eipen (Masumi Okada), a trumpet player and bandleader. His jealousy aroused, Tatsuya ends up attacking Eipen as the musician’s friends come to the rescue. Then the T-School boxers join in and a major brawl trashes the club. During a climatic moment during the chaos we see Eiko and Tatsuya laughing together underneath the bar.

If the first half of Season of the Sun unfolds like an edgy, unconventional romance crossed with a boxing drama, the second half descends into tragedy. The turning point occurs after Eiko and Tatsuya spend a blissful day at the ocean and make love in a sailboat. Embracing him, Eiko sheds tears of joy and confesses “I am no longer alone.” Her strong feelings and admission of love is a surprise to both of them but Tatsuya’s response is muted and becomes increasingly cool.

As Eiko becomes more desperate over Tatsuya’s nonchalant behavior, he retaliates with cruelty, encouraging his older brother Michihisa (Ko Mishima) to enjoy her as one of his cast-offs. Eiko readily accepts her degradation as proof of her true love for Tatsuya but even Michihisa becomes repulsed by his brother’s behavior, saying, “It’s a dirty trick to break a girl’s heart like this.” In Ishihar’s view of this sun tribe society where women are definitely subservient figures, Eiko is a sacrificial lamb who has chosen her own path and therefore not someone to pity. As for Tatsuya, he is so imprisoned by his macho self-image that he is incapable of being able to express any feelings other than anger or aggression.

Season in the Sun struck a chord with younger moviegoers and became a huge hit but it was only the first of several “Sun Tribe” films. Crazed Fruit (1956), also written by Ishihara, is in a similar vein with two brothers vieing for the same girl during a decadent summer idyll that ends tragically. Other significant “Sun Tribe” films include Nisshoku no Natsu (English title: Summer in Eclipse, 1956), directed by Hiromichi Horikawa for Toho studio, Shokei no Heya (English title: Punishment Room, 1956), directed by Kon Ichikawa for Daiei studio, and Kyônetsu no Kisetsu (English title: The Warped Ones, 1960), one of the last films in the “Sun Tribe” cycle by Koreyoshi Kurahara for Nikkatsu studio.

The ”Sun Tribe” films and their stories of disenfranchised Japanese youth were soon eclipsed by the arrival of the Japanese New Wave and directors such as Nagisa Oshima, Seijun Suzuki, Masahiro Shinoda and Shohei Imamura whose portrayals of the younger generation and society were even more radical and sexually explicit than their predecessors.

Most of the “Sun Tribe” movies and their imitators are difficult to see today with the exception of Crazed Fruit and The Warped Ones, both of which have been released on DVD by The Criterion Collection. Admittedly, Crazed Fruit, directed by Ko Nakahira, is the most accomplished of the “Sun Tribe” films with its clearly drawn characters, stylized direction, dazzling cinematography and intense performances. Yet Season of the Sun still remains fresh, unconventional and surprisingly daring for its time despite an avoidance of nudity or explicit sex. For example, the teenage boys and girls depicted in Furukawa’s film wear coats and ties and fancy dresses respectively when they go to nightclubs unlike the blue jean/leather jacket wearing youngsters of Rebel Without a Cause. But their fashionable appearance is simply a reflection of their arrogance and superior attitude over their detractors. Any opposition to their desires is also usually met with violence for this is a culture where macho bullies triumph.

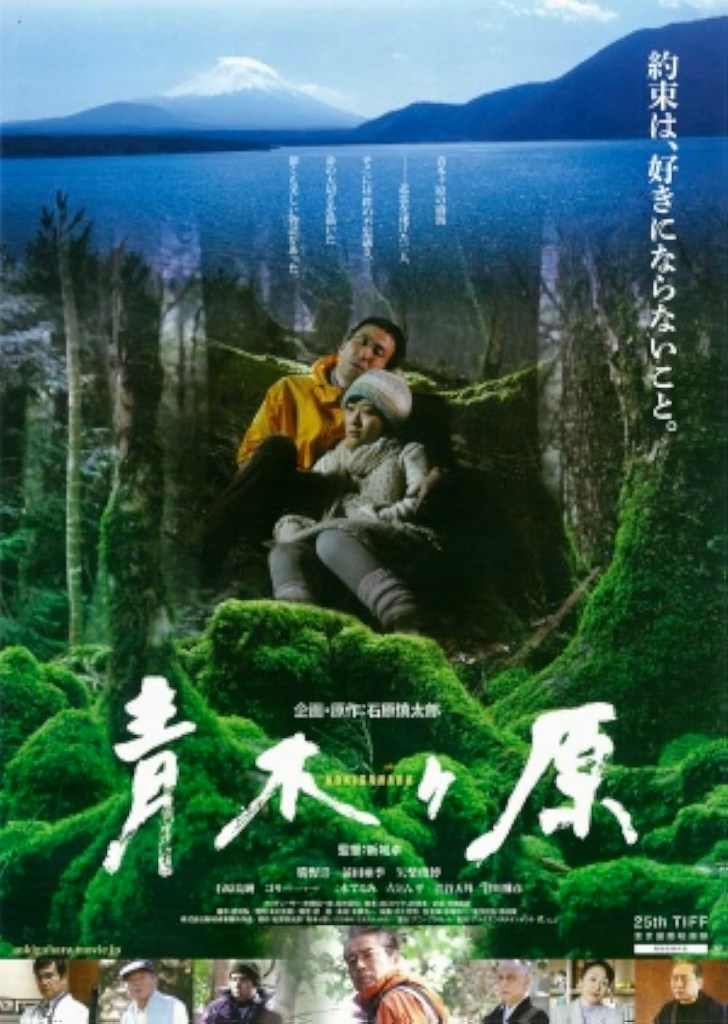

Takumi Furukawa, director of Season of the Sun, had a relatively undistinguished career compared to screenwriter Shintaro Ishihara. The noir-inspired Cruel Gun Story (1964) starring iconic bad boy Jo Shishido is probably Furukawa’s most famous movie. Ishihara, however, would go on to pen several more “Sun Tribe” entries followed by numerous crime dramas like Rusty Knife (1958) and Pale Flower (1964), which is often considered one of director Masahiro Shinoda’s peak achievements. Despite the fact that Ishihara left the film industry to enter the political arena in 1968, he continued to write film screenplays right up to 2012 with his final effort, Aokigahara, based on his novel about the legendary “suicide forest” on the northwestern flank of Mount Fuji.

Among the cast members of Season of the Sun who would go on to prominent careers are Yoko Minamida (as Eiko) and Hiroyuki Nagato (as Tatsuya). They became a couple during the making of this film and would marry in 1961. Together they made at least 25 films together but also garnered accolades separately for key roles. Minamida can also be seen in Kenji Mizoguchi’s A Story from Chikamatsu (1954), Seijun Suzuki’s Voice Without a Shadow (1958) and House (1977), Nobuhiko Obayashi’s cult horror freakout in which she plays the cameo role of Aunt Karei. Among Nagato’s stand-out performances are Shohei Imamura’s My Second Brother (1959) and Pigs and Battleships (1961), Koreyoshi Kurahara’s I Hate But Love (1962) and Noboru Nakamura’s Twin Sisters of Kyoto (1963).

Other familiar faces in Season of the Sun include Yujiro Ishihara (in the role of Izu, one of the T-school boxers) and Ko Mishima (as Tatsuya’s older brother). Ishihara would become a major star at Nikkatsu specializing in crime dramas like I Am Waiting (1957) and Red Pier (1958) while also establishing himself as a pop singer who was often called “the Japanese Elvis.” Mishima, though lesser known, would become a popular supporting player appearing in superior genre films like Masaki Kobayashi’s The Thick-Walled Room (1956), the action adventure The Gambling Samurai (1960) and the sci-fi thriller The Human Vapor (1960).

Masaru Sato, the film composer for Season of the Sun, is also a significant contributor. His unique blending of Spanish acoustic guitar melodies, Hawaiian pop ballads and California’s West Coast jazz influences give Furukawa’s film a unique musical vibe of its own. Sato would go on to become one of Japan’s most acclaimed composers, contributing numerous scores to the films of Akira Kurosawa (Throne of Blood [1957], The Bad Sleep Well [1960], High and Low [1963], etc.), Hideo Gosha (Cash Calls Hell [1966], The Wolves [1971), Violent Streets [1974], etc.) and sci-fi/horror thrillers like Godzilla Raids Again (1955), The Vampire Moth (1956) and The H-Man 1958),l

Season of the Sun has never been given an authorized release in the U.S. on DVD or Blu-ray but deserves to be considered as a possible future release by The Criterion Collection, Arrow Films or Radiance. It is currently streaming at the Cave of Forgotten Films website in a good print with English subtitles.

Other links of interest:

https://www.tokyocowboy.co/articles/sun-tribe

https://variety.com/2009/scene/people-news/yoko-minamida-dies-at-76-1118010614/

https://jfilmpowwow.blogspot.com/2011/05/actor-hiroyuki-nagato-1934-2011.html

https://mubi.com/en/notebook/posts/koreyoshi-kurahara-part-i-black-sun-and-the-sun-tribe