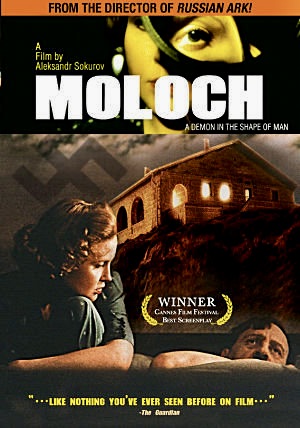

Still shrouded in mystery and speculation by historical experts, the final days of Adolf Hitler remain a subject of endless fascination for many. It’s certainly been the focus of several films such as the 2004 German production Downfall (Oscar nominated for Best Foreign Language Film) and Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973) starring Alec Guinness, but Moloch (1999), from Russian director Aleksandr Sokurov, is not a typical biopic or dramatic reenactment but an unconventional and startling chamber piece, closer in style to an off-Broadway ‘Theatre of the Absurd’ production.

Set at Hitler’s alpine retreat known as The Kehlesteinhaus (Eagle’s Nest) near the southeast German town of Berchtesgaden in 1942, just prior to the German army’s defeat at Stalingrad, Moloch focuses on one day in the life of the Fuhrer (Leonid Mozgovoy), beginning with his arrival at the castle. His mistress, Eva Braun (Yelena Rufanova), is already there, eagerly awaiting his visit. Traveling with Hitler is his deputy, Martin Bormann (Vladimir Bogdanov) and his minister of propaganda Dr. Josef Goebbels (played by female actress Irina Sokolova), accompanied by his wife Magda (Yelena Spiridonova).

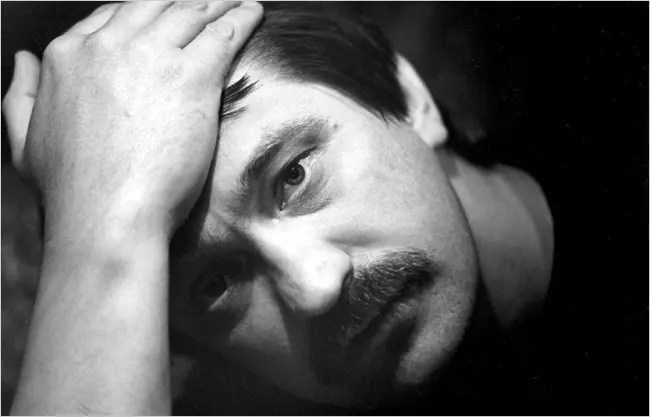

Sokurov’s Fuhrer is not the ranting despot glimpsed in newsreels or a broad caricature like Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) but a moody, self-absorbed man whose mental stability is already in question. He comes across more like a neurotic hypochondriac than the infamous dictator of history books. He obsesses over his health, complains about his sensitive nose (telling Bormann he smells like mustard gas), flaunts his vegetarian views at mealtime while offering his guests “corpse tea,” and at one point he plays conductor while 16mm footage of an orchestra is projected on a screen.

Yet, despite his increasingly erratic behavior, Hitler’s guests remain raptly attentive, either out of fear or blind obedience. Only Eva (whose nickname for Adolf is ‘Adi’) has the courage to argue with him behind closed doors. Within the claustrophobic, tomb-like atmosphere of the castle, she is the only spark of life, a fact confirmed by her first appearance in the film, performing gymnastics in the nude on the battlements of the fortress.

Alternating between studio sets filmed in dreamy soft-focus (at the Lenfilm studio) and stunning natural locations in the Bavarian mountains, Moloch casts a strange spell indeed. There are times when the film borders on outright parody such as the scene where Bormann takes a pratfall at dinner or the depiction of Goebbels as the odd-man out in Hitler’s inner circle; no matter what he says or does, the Fuhrer treats him as an object of derision.

And what are we to make of scenes where Eva confesses she doesn’t really know who Germany is fighting or Hitler’s blank response to a mention of Auschwitz as if he’s never heard of it? Is Sokurov playing the provocateur here or simply presenting a “what if” scenario?

According to one interview, Sokurov approached Moloch from a moral viewpoint, stating, “For a Christian it’s through love that one finds the essence of salvation. But can one save one’s soul by loving a monster? That’s the question that troubled me the most. Eva Braun, according to existing memoirs, was capable of sacrificing herself for love. Because of this, she was doomed for a tragic existence. She is the main character of the film.”

One thing the director makes glaringly obvious in this intimate portrait of Hitler’s inner circle is that the women in their lives were considered inferior to them and their intelligence was often derided. In one telling scene, Hitler states with certainty that “Comprehension is strictly a masculine faculty. The more stupid a woman is, the most expensive she is. It’s not by chance that the wives of great men were all idiots.

The title Moloch is a reference to the Semitic god to whom children were sacrificed. Originally conceived under the working title of The Mystery of the Mountain, this was the first in a planned tetralogy of films by Sokurov to deal with the corrupting effects of power; the other three are Taurus (2001) about the final days of Lenin, Solntse aka The Sun, his 2005 portrait of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, and Faust (2011), based on the famous Johann Wolfgang von Goethe play.

Of course, this is not the first time Sokurov has turned to Hitler as a subject for his camera. His short film, Sonata for Hitler (1989) is composed completely from German newsreel footage and through artful editing becomes a subtle critique of Fascism.

One other interesting fact about Moloch is that it marks the first time Sokurov used professional actors for all the main roles; usually the director preferred to work with non-professionals resulting in acclaimed masterworks like the haunting Mother and Son (1997). The odd thing is the director hired Russian actors for Moloch but then had them all dubbed in German by well-known actors such as R.W. Fassbinder regular Eva Mattes, who provides the voice of Eva.

In real life, Eva Braun was known to be apolitical and led a sheltered and privileged existence. Her relationship with Hitler was kept secret outside the Fuhrer’s inner circle and she was said to have had little influence on his views, being viewed as little more than an amiable homemaker and sex partner. What makes Moloch especially intriguing is her depiction as a much more complicated character, one who is starting to show signs of frustration and sadness at her limited role in his life. During a quarrel in Hitler’s bedroom in the film, Eva demands, “Who contradicts you besides me?” and he responds with, “Tell me something insolent!” Her comeback is, “You don’t know how to be alone. Without an audience, you’re nothing more than a corpse.” His lack of a reply seems to mirror his own raging insecurities and fears.

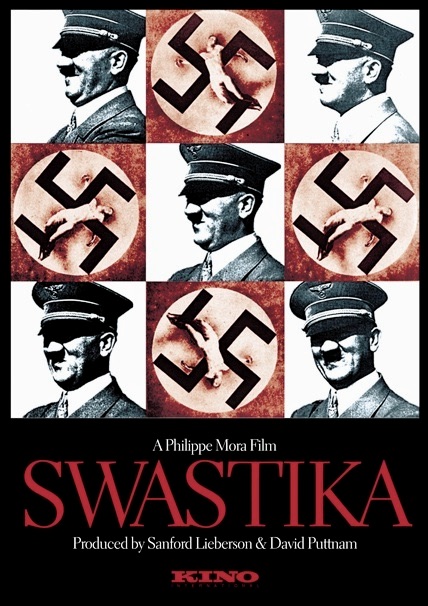

Moloch might be the only cinematic attempt to dramatize Eva Braun as a character but there have been various documentaries on her, which utilized her home movies of holidays at Eagle’s Nest with Hitler, such as Philippe Mora’s Swastika (1973) and Dave Flitton’s Eva Braun: Hitler’s Mistress (1991).

At the time of its release Moloch received mixed reviews from critics compared to the acclaim that greeted his previous dramatic work Mother and Son from 1997 but it did win the Best Screenplay award at Cannes (it was written by Yuriy Arabov and Marina Koreneva). The Variety reviewer called Moloch “a disappointingly shallow film that is unlikely to win him [Solurov] new friends in the international film community. With its stately pacing and characteristically distinctive but audience-unfriendly diffused visuals – tinged with a green light in most scenes – this intimate study of Adolf Hitler generally fails to deliver the goods.”

A more glowing review by Peter Bradshow appeared in The Guardian and stated, “…the film from the Russian Aleksandr Sokurov, brings off something really remarkable: performances by Leonid Mosgovoi and Elena Rufanova – Russian actors dubbed with German voices – which achieve a horribly plausible approximation of the domestic life, and indeed what passed for the sex life, of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun…Sokurov imagines a tragic interior life for Eva, who is given an intelligence and wit above and beyond reality. Ultimately, Mosgovoi’s Hitler is so convincing, that there are times when it is almost hair-raising.”

Released on DVD by Kino Lorber in 2005, Moloch includes a featurette on the making of the film with comments by the director. It has yet to make its debut on Blu-ray or 4K

*This is a revised and expanded version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

Other links of interest:

https://reflectionandfilm.blogspot.com/2012/03/paul-schrader-interviews-aleksandr.html

https://www.russialist.org/archives/7225-12.php

https://www.new-east-archive.org/articles/show/4695/sokurov-interview-Francofonia-venice