1950 marked an important turning point in the evolution of the Hollywood Western and Broken Arrow, directed by Delmer Daves, was largely responsible for that. A sympathetic treatment of the plight of the Apache people and their way of life, the film was the first major studio western to depict Native Americans as something other than bloodthirsty savages or naive primitives. The real hero of Broken Arrow was Cochise (Jeff Chandler), the Apache leader, and not the cavalry scout (James Stewart) who marries an Apache woman (Debra Paget). The film’s liberal views on race and the white man’s treatment of the Native-American were considered daring at the time and garnered much critical acclaim. It also earned three Oscar nominations including one for Best Screenplay (by Michael Blankfort). The downside of all this is that Broken Arrow‘s success completely overshadowed Devil’s Doorway, which was released the same year and also addressed the terrible treatment of this nation’s original settlers.

The truth is that Devil’s Doorway was completed first but held back from release due to the nervousness of MGM’s studio brass over the subject matter. When Broken Arrow proved to be a box office hit, the studio released Devil’s Doorway but it was largely ignored by critics and the public. The irony of all this is that, seen today, Broken Arrow seems preachy and patronizing whereas Devil’s Doorway, directed by Anthony Mann, stands out as a much more realistic and grim depiction of how the west was really won.

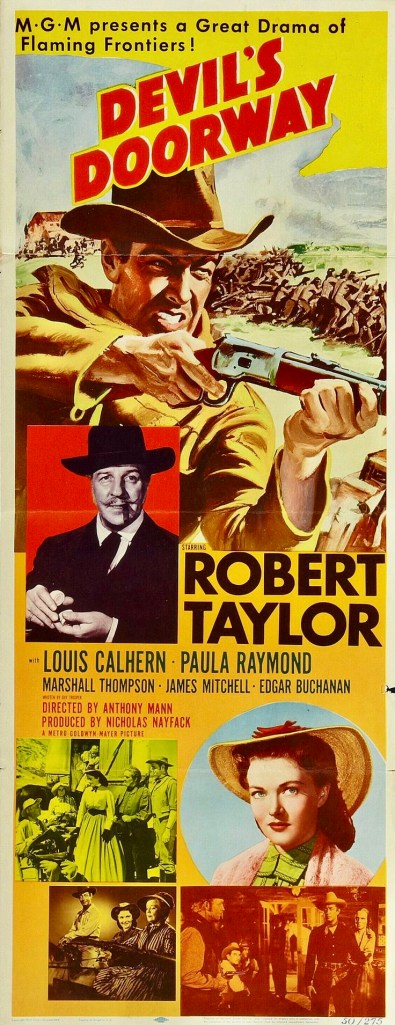

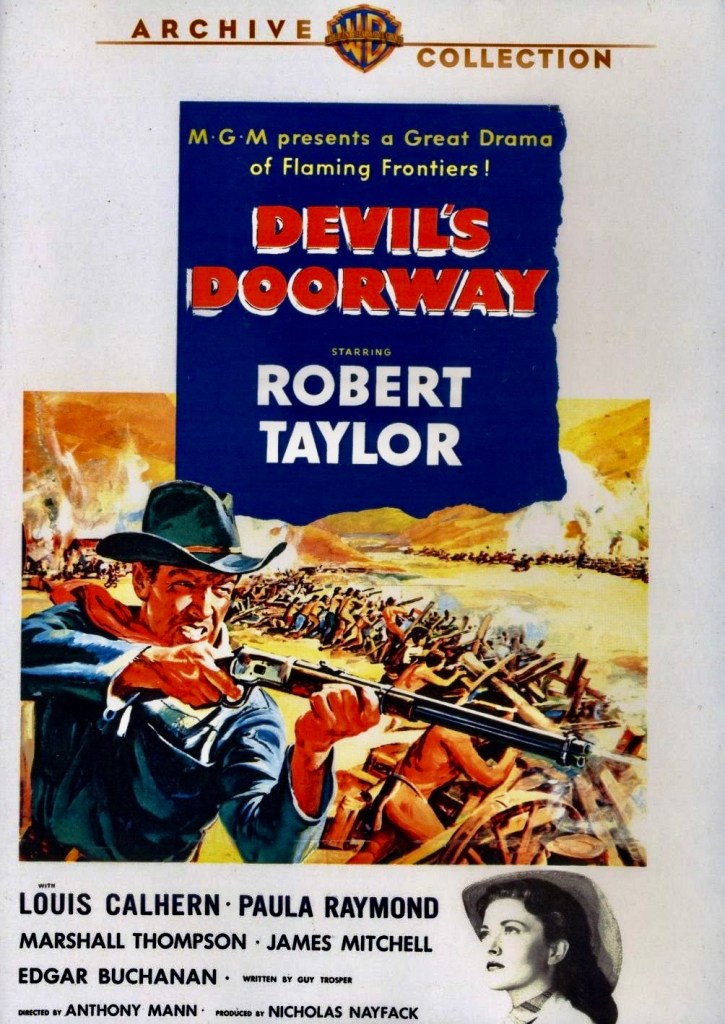

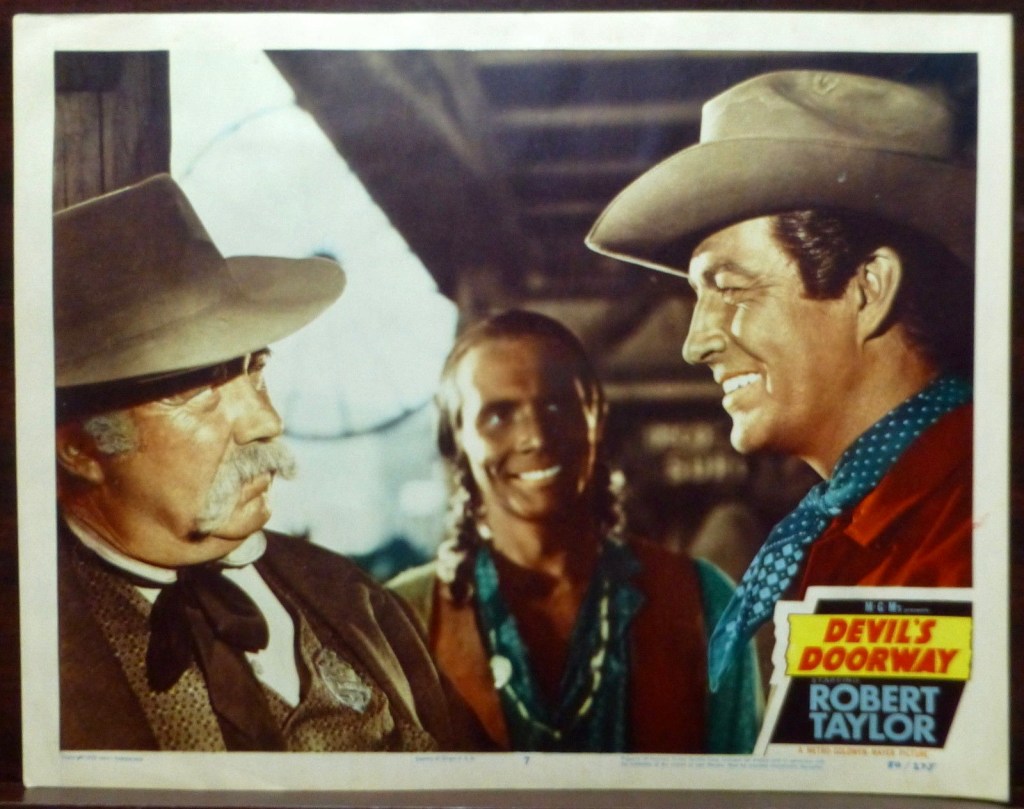

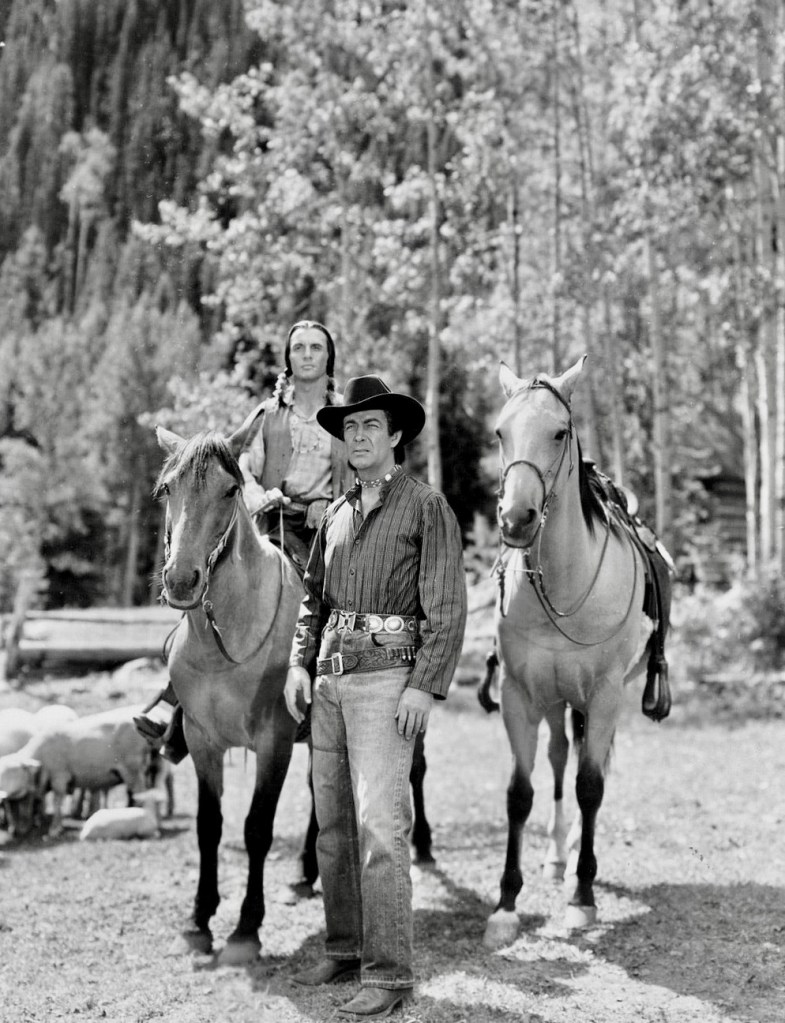

In Devil’s Doorway, Robert Taylor stars as Lance Poole in dark skin makeup (a standard Hollywood practice at the time when Caucasian actors were cast in ethnic roles). He is a Shoshone Indian who has just returned to his people in Wyoming from fighting for the Union in the Civil War. Despite having won a Congressional Medal of Honor, his reception back home from the white community is less than welcoming. His dying father warns him that the acreage that they have tended and farmed for years will be taken from them by the government but Poole remains optimistic until he gets a taste of the white man’s law. He quickly learns that an Indian is not a legal citizen of the United States and has no land-owning rights. Soon a corrupt, racist lawyer (Louis Calhern) stirs up hostile feelings toward the Shoshone tribe in town and encourages homesteaders to come and stake claims on Poole’s land. At first Poole attempts to use legal means to protect his rights by hiring the only other lawyer in town – O. Masters (Paula Raymond), who turns out to be a woman to his great surprise. Despite the best intentions, Masters’ case for Poole is undermined and rendered ineffective by the white establishment lawmakers and Poole is left to take matters into his own hands with violence and senseless slaughter the end result.

Devil’s Doorway was Anthony Mann’s first western and marked the beginning of a remarkable period in his career when he revitalized the genre with a series of brilliant films, many of which starred James Stewart (Winchester ’73 (1950), Bend of the River (1952), The Far Country, 1954) and featured psychologically complex characters and stunning natural settings, mostly filmed on location in Colorado. According to Mann, Devil’s Doorway began with a phone call: “I was under contract to Metro and had just made my first film for [producer] Nicholas Nayfack. Nicholas called me and asked, “Would you like to make a western? I’ve a scenario here that seems interesting.” In fact, that “interesting” scenario was the best script I’ve ever read! I prepared the film with the greatest care…” (The screenplay is by Guy Trosper, who also penned The Stratton Story [1949] and The Pride of St. Louis [1952]).

Mann requested and got MGM star Robert Taylor for the lead role and John Alton to handle the cinematography. Alton had previously collaborated with Mann on a string of taut, atmospheric film noir thrillers such as T-Men (1947) and he brought a similarly dark and ominous look to Devil’s Doorway. The film’s expressionistic lighting and stark vistas have often been compared to the look of an Ansel Adams photograph and some sequences have a power and intensity that practically leap off the screen.

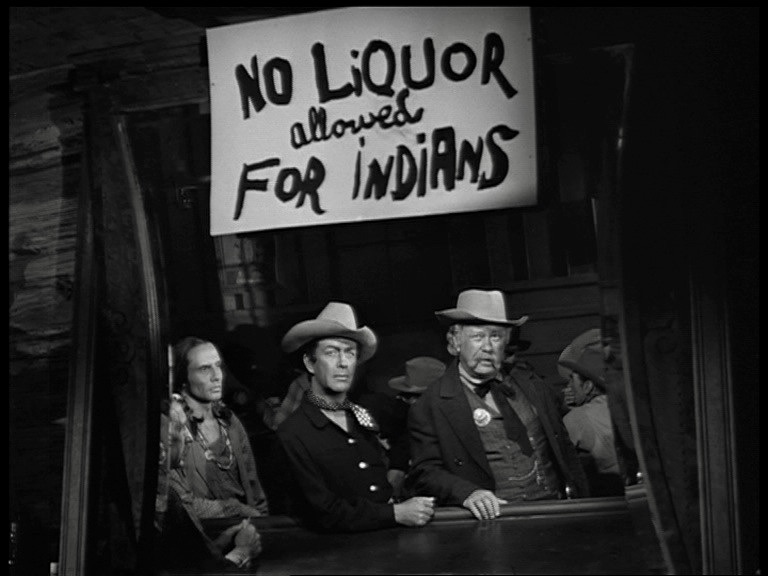

The barroom confrontation scene between Poole and a bullying gunslinger, in particular, is a casebook example of Alton’s style. A sense of menace is established from the opening shot as Poole and his Shoshone companion enter the bar and thunder cracks in the distance, signaling an approaching storm. Inside, Coolan and his hired gun are in the foreground as we see Poole from their point of view, being refused service at the other end of the bar – “No liquor for Indians.” After being threatened at gunpoint, Poole attacks his oppressor and the brawl alternately mixes close-ups of the fighters’ contorted faces with passive reaction shots of the neutral observers while the deadly free-for-all is occasionally illuminated by flashes of lightning. There is no dramatic music used, only the sounds of the two men fighting and the outside storm. Rarely has the struggle between good and evil been visualized on screen in such potent, primeval terms.

Devil’s Doorway is also unique for its refusal to fall back on the clichés of the genre. There is no romantic subplot to detract from the rising tension in the narrative and no “happy ending” for our hero either – the movie ends in genocide with the surviving Shoshone women and children being escorted by the cavalry to a reservation. Most unconventional of all is the introduction of O. Masters, the female lawyer, who seems like an anachronism in the frontier town of Medicine Bow. But, like Poole, she’s an outsider in her own community who is further discredited for representing and defending a Shoshone Indian. While there is an undeniable attraction between Masters and Poole they never acknowledge it directly though they are well aware of how the racist townspeople will view their mutual alliance.

Many critics at the time felt that Robert Taylor was completely miscast in the role. Despite the exaggerated dark skin makeup, however, Taylor delivers a forceful and commanding performance as Poole. Long past the matinee idol stage of his career, Taylor had matured into an impressive actor by this point in his career. His once boyishly handsome features had hardened into a stoic, world-weary mask which made him ideal casting for tough, uncompromising characters. And even though Taylor had made a few westerns in his career prior to Devil’s Doorway, his best work in the genre can be found in the fifties starting with this Anthony Mann film and continuing through the early sixties with such high points as The Last Hunt (1956) and The Law and Jake Wade (1958) along the way.

As noted earlier, Devil’s Doorway was unfairly dismissed by most critics upon its release as being a less successful imitation of Broken Arrow but there were some favorable reviews such as The New York Times which deemed it “a Western with a point of view that rattles some skeletons in our family closet.” But the film’s most ardent admirers would emerge much later when the movie was finally seen by film scholars in the context of the Hollywood Western and Mann’s career. Jeanine Basinger in her book Anthony Mann wrote that Devil’s Doorway “is not only an honest portrayal of the plight of the Indian, but it also has an interesting portrait of a preliberation woman. It is in every way a modern film.”

And Phil Hardy in his reference work, The Encyclopedia of Western Movies, said “What makes the film so impressive is [Guy] Trosper’s articulate script and Mann’s handling of the theme of identity – the major theme of Mann’s series of classic Westerns in the fifties – with Taylor caught – literally, his dress alternates between that of Indian and white man – between the conflicting identities and loyalties of Indian and American.” In the end, Anthony Mann has the final word on Devil’s Doorway: “I think the result was more powerful than Broken Arrow, more dramatic, too.” An immodest statement perhaps, but undeniably true.

Devil’s Doorway was difficult to see for many years outside of occasional screenings on television on Turner Classic Movies and other classic film channels. It was finally released by Warner Brothers on DVD in 2010 but an even better option for collectors is the Blu-ray edition, which appeared in May 2024 and the extras include the theatrical trailer and two vintage WB cartoons, The Chump Champ (1950) featuring Droopy and Cue Ball Cat (1950) starring Tom and Jerry.

*This is a revised and expanded version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

Other links of interest:

https://roberttayloractor.blog/

http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.fil.062