Smoke fills the screen and drifts toward the sky. We see black earth that is steaming and could be cooling lava. Then we notice small holes punched into the dark topography where smoke is being released. A wide shot reveals that we are looking at a mound of charred material that is being raked by a worker at the top of the heap. Where are we and what are we looking at? Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte (2010), which roughly translates as The Four Times, is an immersive but often disorienting portrait of life in the village of Caulonia, Italy, which often requires the viewer to make sense of a visual detail or local ritual without a frame of reference. This is not detrimental, however, to the film’s exploratory narrative but one which is enriched by a sense of mystery and wonder.

Le Quattro Volte is hard to pigeonhole in terms of genre. It is not a documentary although it looks and feels like one. You could hardly describe it as a traditional fiction film either since there is no dialogue or narration to advance the storyline, nor is there a major protagonist. Instead, Frammartino has created a poetic meditation on the interconnectivity between people, animals, plant life and organic material which becomes apparent as his cinematic vision unfolds. Using the local residents of Caulonia and occasionally staging situations and events as they commonly occur in the hillside village, the director provides a glimpse into a world rarely seen by outsiders.

Until recent years, Calabria, Italy, has been considered the most backward and economically depressed region of Italy (it still has the highest unemployment rate in its country). Villages like Caulonia are not tourist destinations and actually seem disconnected from contemporary Italy. In fact, the local villagers exist as if they were in some kind of time warp, most of them following practices that will probably end with their demise. This is exactly what makes Le Quattro Volte fascinating and a testament to Frammartino’s eloquent depictions.

In the official press release for Le Quattro Volte, the director admitted that the film’s title and its structure was inspired by the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras. Paraphrasing the philosopher, Frammartino stated, “Each of us has four lives inside us which fit into one another. Man is mineral because his skeleton is made of salt; man is also vegetable because his blood flows like sap; he is animal in as much he is endowed with motility and knowledge of the outside world. Finally, man is human because he has the gifts of will and reason. Thus, we must know ourselves four times. [Pythagoras lived in Croton in present-day Calabria during the 6th century BC. His school taught the doctrine of metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls].”

Frammartino illustrates this concept by following the trajectory of four separate subjects – an elderly herdsmen, a baby sheep, a towering tree in the forest and a charcoal kiln. The type of ethnographical detail the director provides in each episode is often surprising, enigmatic and occasionally comical. For example, the shepherd’s dog creates a village dilemma when he pulls a wooden block out from under the wheel of a small pick-up truck. The vehicle rolls down a slanted street backwards and crashes through the gate of a sheep pen. The animals then wander free through the village, entering houses, crowding the rooms and trying to climb over tables and furniture.

Much more odd is a sequence where the shepherd visits the local church and is given a packet by an employee that contains sweepings from the floor of the church. He later takes a portion of this “holy” dust with a glass of water as if it is some kind or cure.

Le Quattro Volte is full of these kinds of relevatory moments, whether it is the live birth of a baby sheep, an unusual holiday tradition of hauling a freshly cut tree, stripped of its bark, into the village square where it is raised again for an annual celebration or the creation of a charcoal kiln, which looks like the work of some environmental artist. It is not surprising that in real life, Frammartino, who was trained as an architect, is also an artist, and has created numerous art installations (his installation Alberi premiered at MoMA PS1 in April 2013).

For those who are familiar with and appreciate slow cinema, Le Quattro Volte is an excellent example of the form and may remind some viewers of the early work of Abbas Kiarostami (Where is the Friend’s House?, And Life Goes On) and Pedro Costa (Ossos, Horse Money). Frammantino has stated that Le Quattro Volte “does not make any direct references to other films. However, my filmmaking is often inspired by cinema’s great auteurs. The first one that comes to mind is Bela Tarr; the presence of animals is crucial to his cinema…I also think a lot about Bresson and his Au Hasard Balthazar…I admire Michael Snow and his film Le Region Centrale. Another notable influence is Samuel Beckett, who only ever wrote one film, a short film entitled Film, which was shot by Alain Schneider in 1965. Both these films experiment with points of view in which man is not the central figure and in which only machines and recording equipment are used to “see.” I have made monumental examples, but do not wish to compare myself to them. My work is rather artisanal in nature.”

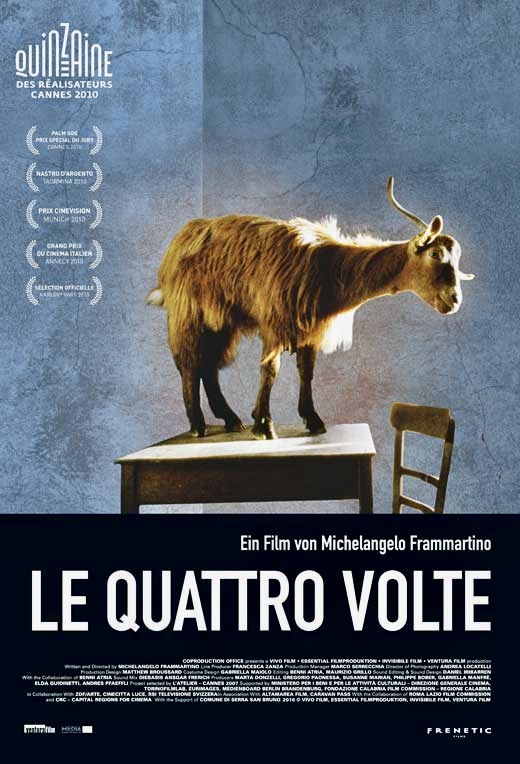

When Frammartino’s film premiered in 2010, it won numerous prizes at the Cannes Film Festival, Munich Film Festival and San Diego Film Critics Society Awards to name a few. The cinematography by Andrea Locatelli and the sound design by Benni Atria are also deserving of high praise. Critics were equally effusive in their assessments with Roger Ebert calling it “a serene and beautiful film” and Natasha Senjanovic of The Hollywood Reporter, noting, “Frammartino has stopped to smell the roses, trees and fields that not long ago at all made up life as we know it, yet which now has been buried or lost forever under layers of modern, man-man constructs…we get so sucked in by the silence and images that the communal gatherings in the small town seem like metropolitan hustle and bustle, and the people with their digital cameras and ipods aliens visiting from a distant future.”

Frammartino first ventured into filmmaking in 1995, creating several movie shorts before making his feature film debut with Il Dono in 2003. The movie toured the film festival circuit but received mixed to negative reviews at best and didn’t prepare anyone for Le Quattro Volte, which appeared seven years later. Despite the universal acclaim that the latter film received, Frammartino didn’t return with a follow-up feature until 2013, more than a decade later. The result, Il Buco (English title: The Hole), is another stunning docu-fiction but it hasn’t had the widespread success of Le Quattro Volte, possibly because it had a much more specific focus: a non-verbal account of a 1961 spelunking expedition of a cave in the Pollino, a mountainous region between Basilicata and Calabria.

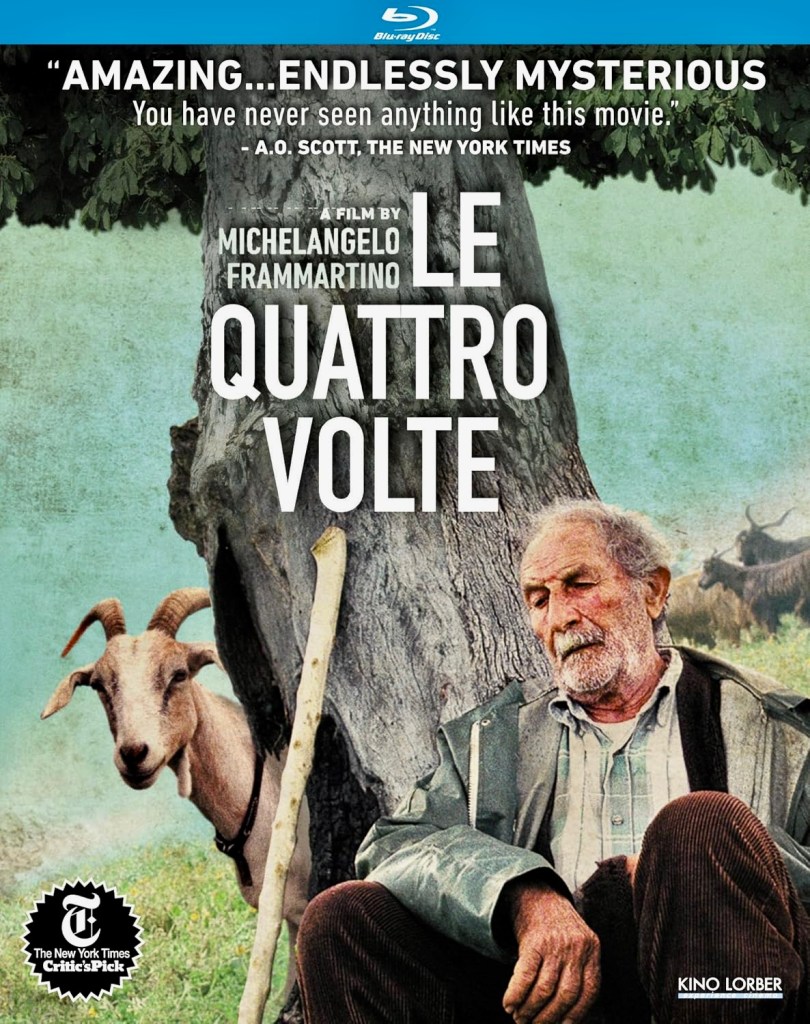

For those interested in purchasing Le Quattro Volte, Kino Lorber offers both Blu-ray and DVD options, which were originally released in September 2011.

Other links of interest:

https://msfilmfestival.fi/en/guests/michelangelo-frammartino/

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2013/12/07/michelangelo-frammartino/