Yutaka Yoshii (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is a twenty-four-year-old man who suddenly wakes up from a coma after ten years and has to readjust to a new world. This is the basic set-up of Ningen Gokaku (English title: License to Live, 1998), a decidedly change-of-pace effort from Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who is better known for creepy occult/psychological thrillers like Sweet Home (1989), Cure (1997) and Pulse (2001). You can only imagine what an American film studio would do with this simple concept – it would either become a rom-com like While You Were Sleeping (1995) or a horror flick such as The Dead Zone (1983) – but Kurosawa takes an approach that probably surprised even his most fervid fans. License to Live turns out to be a low-key, observational series of vignettes that slowly culminate in a moving meditation on the things that make the life of a human being worth living.

At the start of the film, you can easily imagine Kurosawa taking a comic “fish out of water” approach to Yutaka’s dilemma and there are fleeting moments of absurdist comedy throughout License to Live delivered in the deadpan style of an Aki Kaurismaki movie (The Man Without a Past, Le Havre, Fallen Leaves). Nevertheless, the movie subtly involves the viewer in Yutaka’s quest to make sense of what has happened to him. At first Yutaka still acts like the fourteen-year-old teenager he was before a car/bicycling collision put him in a coma. He seems indifferent or uninterested in what has happened during the ten years he was asleep and ignores the pile of magazines, videotapes and books given to him by his doctor to catch up.

What is most surprising is that no one from his family shows up at the hospital to see him. It turns out that while Yutaka was unconscious, his family broke up. His father Shinichiro (Shun Sugata) became a restless wanderer, his mother Sachiko (Lily) moved away to run a clothing boutique and his sister Chizuru (Kumiko Aso) ran off with her clueless boyfriend Kazaki (Sho Aikawa). In fact, Yutaka’s first visitor at the hospital is Murota (Ren Osugi), the man who was driving the car that accidentally caused the accident. He confesses that he is the one who has been paying the hospital bills for ten years and offers Yutaka 500,000 yen if he will forgive him and forget the whole affair. He also adds a parting jab, “You’re not the only one who lost ten years of his life!”

The only other person who comes to visit Yutaka (and ends up offering him a place to live) is Fujimori (Koji Yakusho), a longtime friend of Shinichiro who is now running a fish camp on the Yoshii family property. Fujimori becomes like a surrogate father to Yutaka but is clearly uninterested in playing the parent and is only doing it out of loyalty to Shinichiro. He tries to force his new housemate to engage in the world and learn new things like driving a car (which almost ends in disaster). He even tries to trigger his sexual libido by taking Yutaka to an erotic massage parlor but the boy rates the experience as “just so so” and “once is enough.” Fujimori is baffled by Yutaka’s apathy and lack of curiosity until the latter exclaims, “If I don’t know what I lost, how can I get it back?”

A turning point occurs when a runaway horse arrives on Fujimori’s property and Yutaka becomes excited and engaged for the first time since he woke up. He wants to keep the horse and start a dude ranch on a mini-scale with the horse as the main attraction. It all links back to Yutaka’s childhood when his family owned a horse farm and was one of his happiest memories. When the owner of the horse comes to retrieve his animal, Fujimori pays him off and Yutaka proceeds with building a horse ring, painting it white, and eventually adding a milk bar.

In the midst of this new development, Yutaka experiences a reunion with each of his family members separately, starting with his father who has just returned from a sojourn to Europe and is now planning to travel to Africa as a missionary. For a brief time his mother and sister and Kazaki even end up helping Yutaka run the dude ranch and milk bar. In an unguarded moment Yutaka says wistfully to his mother, “Just for a moment couldn’t we all be together again?”

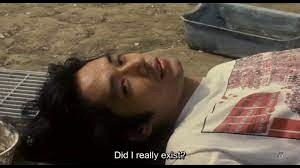

By this point we realize that Yutaka has been living in the past since he came out of the coma. His sense of isolation and loneliness has been replaced by his desire to be part of a loving family again but is it all just a fantasy? In a revelatory scene toward the end, Yutaka asks Fujimori, “Am I dreaming? Did I really exist?” License to Live concludes as Yutaka relinquishes his obsession with the past in order to move ahead into the future but it does so in an unexpected but touching resolution.

Kurosawa’s film may sound simplistic and didactic from my synopsis but it is surprisingly unsentimental and thought provoking in execution. The director often avoids showing us key scenes which could possibly shed more light on Yutaka’s character such as his encounter at the massage parlor or his evening with former classmates at a high school reunion. Instead, we have to imagine what Yutaka is going through from watching his physical movements, posture and facial expressions and it is much more rewarding.

The episodic nature of License to Live is also tautly edited with some scenes serving as little more than reaction shots to a situation or ending before an argument has been resolved or a conversation has ended. This gives the film a sense of underlying tension as well as a hypnotic rhythm. In general, the big dramatic moments are internalized but there are a few exceptions such as the scene where an irate Murota visits the dude ranch and wreaks havoc, shouting at Yutaka, “I ruined your life, you ruined mine. We’re fifty fifty. That’s just how it is. I agreed to that. But you’re NOT allowed to be happy.”

While License to Live is quite a departure from Kurosawa’s more familiar genre work like Creepy (2016) and Serpent’s Path (1998), it does share some similarities in terms of the visual aesthetics and marginalized characters who feel alienated from their surroundings. The cinematography (by Jun’ichiro Hayashi), in particular, plunges us into a world that is alternately sterile and antiseptic (the hospital scenes) and one that is messy and disorganized (Fujimori’s junkyard house and yard). Other Kurosawa trademarks include his use of static shots of characters in a room (often seen through the outside perspective of a window) or pans to establish the emotional resonance of the moment.

There is also the presence of Koji Yakusho, one of Kurosawa’s favorite actors, in the sympathetic role of Fujimori. You will recognize him from his memorable work in Cure, Charisma (1999), Pulse, Doppelganger (2003), Retribution (2006) and Toyko Sonata (2008), which many consider Kurosawa’s masterpiece. In fact, License to Live, after 10 years before Tokyo Sonata, is, in some ways, a precursor to that movie with its tale of a family that falls apart after the father loses his job.

License to Live was mostly well received by the handful of critics who saw it. The review in the U.K. publication TimeOut said, “Sundance alumnus Kurosawa previously looked more like an ambitious genre technician than the commentator on existential dilemmas he proves to be here. To his great credit, he frames the whole thing as black comedy and delivers the wryest of surprise endings.”

I felt like the black comedy aspect of the film was quite muted and used sparingly and seem to side more with the reviewer for JapanonFilm who wrote, “As with so many Japanese movies, what we see is what we get, and life is what it is, no more and no less. We are born, or in this case re-born, and then we die. Perhaps it is a Buddhist allegory, or perhaps not…This movie seems a change of direction and is the only one of his movies that might be called “comic” by some viewers, but it fits securely into his basic themes, just as its visual and narrative style fits securely into the quiet observational camera of the uniquely Japanese tradition.”

Many of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s films are available in the U.S. on DVD and Blu-ray but License to Live remains elusive in terms of availability. Given the director’s popularity, it is bound to be released on Blu-ray domestically at some point but, in the meantime, you can stream a nice print of it with English subtitles on the Cave of Forgotten Films website.

Other links of interest:

https://www.international.ucla.edu/asia/article/106374

https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/interview-kiyoshi-kurosawa/

https://www.ign.com/articles/2001/08/23/interview-with-director-kiyoshi-kurosawa

http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/kiyoshi-kurosawa/