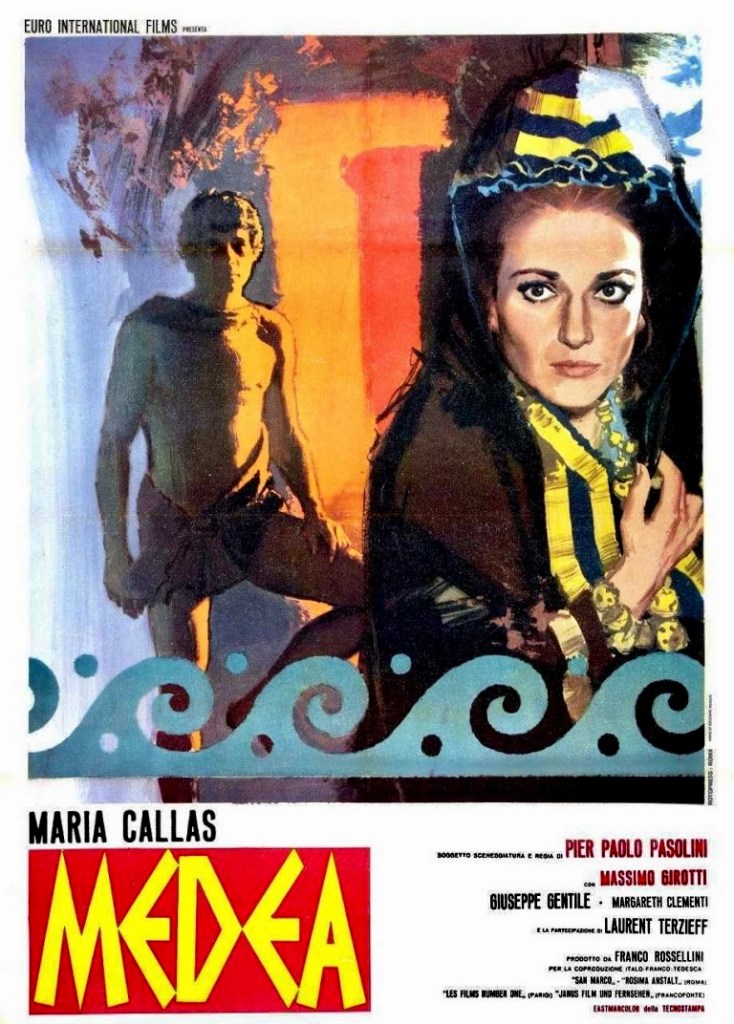

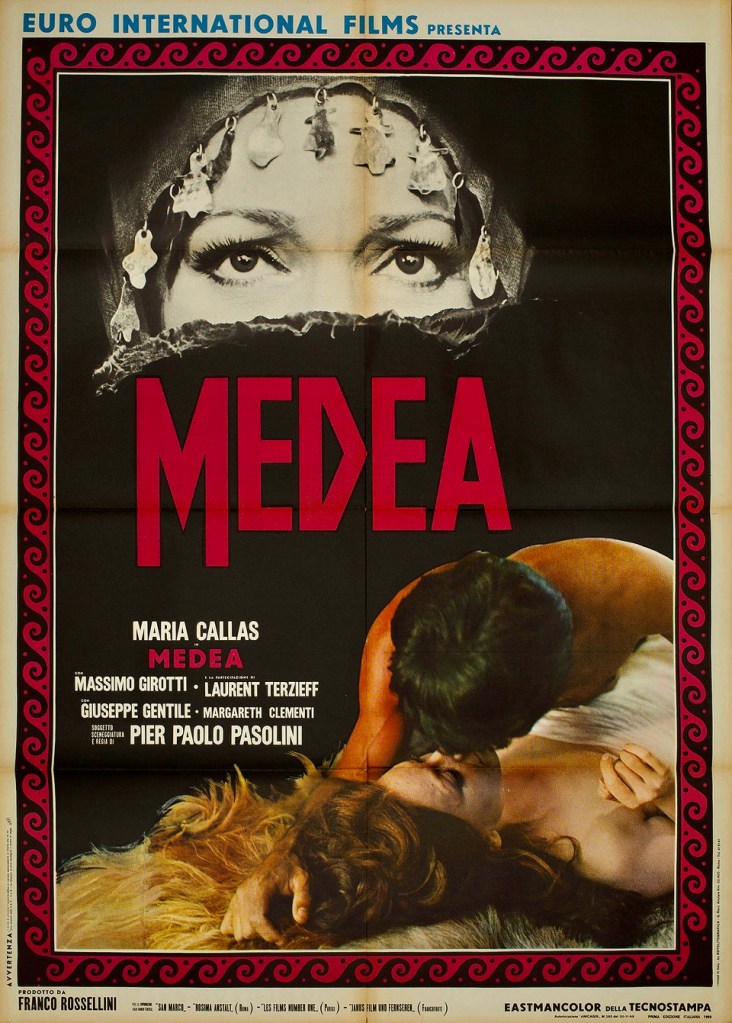

Are you well versed in Greek mythology? You’ll need to be if you take a deep dive into Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1969 version of Medea starring the world’s most famous opera diva Maria “La Divina” Callas in her only feature film role (and she doesn’t sing). Freely adapting narrative elements from the original Greek myth as well as Euripides’ play, which was first performed in 431 BC, Pasolini presents the tragic tale in the manner of a social anthropologist crossed with an experimental filmmaker dissecting an ancient case history of a marriage gone wrong. If you aren’t familiar with the story of Jason and Medea, this interpretation can be confusing, mysterious and inaccessible at times but it is also one of the most visually and aurally dazzling of the many versions produced on stage, TV or film over the years.

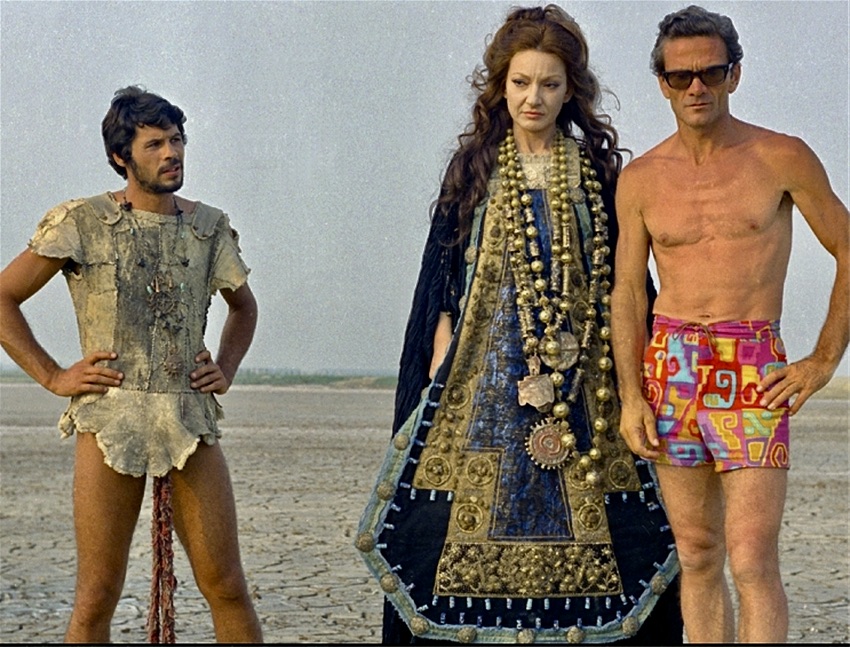

The Greek myth of Medea depicted her as a sorceress who helped Jason, the leader of the Argonauts, in his quest for the legendary Golden Fleece. With her brother Apsyrtus, she stole the fleece from her father, King Aeetes of Colchis, and fled the country for Corinth with Jason. They marry and raise two sons together but there is no happy ending in the cards. The Euripides play actually opens at the point where Jason (Giuseppe Gentile) has become bored with Medea (Maria Callas) and leaves her for Glauce (Margareth Clementi), the daughter of King Creon (lMassimo Girotti). Medea pretends to accept her fate with no hard feelings but plots an elaborate revenge instead. In her desire to destroy Jason’s happiness, she presents his bride-to-be with a deadly garment which kills her and then sacrifices her two sons before burning their home to the ground.

This basic storyline is not clearly delineated in Pasolini’s rendition which features minimal dialogue except for an opening sequence which depicts Jason’s early years under the tutelage of Chirone (Laurent Terzieff in a dual role as a centaur and his human counterpart). Characters rarely, if ever, address each other by name and many of the events that unfold seem more like ancient rituals enacted by members of a bizarre cult. Take, for example, the figure of Apsyrtus (Sergio Tramonti), who helps Medea steal the Golden Fleece from their father. His identity is never clear in Pasolini’s version. Is he a loyal follower, a potential lover or relative? And why does Medea brutally murder and dismember him after he helps her with her scheme? In Euripides’ play, Medea killed her brother and left his body parts scattered across her escape route as a diversion tactic, knowing her father and his troops would stop to collect and bury Apsyrtus’s remains while she made her getaway. You’d never know the motivations for her actions in Pasolini’s version, which also avoids dramatizing Jason’s callous rejection of Medea for Glauce.

In this 1969 version, Jason is not the fearless and self-absorbed adventurer of the Greek myth but a handsome, affable and seemingly passive figure who suddenly leaves his wife for another woman (we never see Jason’s growing infatuation with Glauce or the events that lead to their marriage ceremony.) As a result, Medea’s wrath seems not just inexplicable but psychotic.

There are also two varying depictions of Glauce’s demise. In the first one, she puts on Medea’s gift of a cloak and bursts into flames, dying a hideous death (is this Medea’s mental fantasy of what will happen?). In the second variation, Glauce puts on the wedding offering and becomes hysterical, throwing herself off a tower to die below. Her father witnesses the tragedy and follows suit, resulting in a double suicide.

What is most surprising is that Pasolini shows little interest in playing up the emotional and dramatic possibilities of the climax when Medea kills her two sons. The killings happen off camera and her manner is more serene and loving than rage driven.

Pasolini, however, is not interested in a straightforward account of the famous story but approaches it as a visual spectacle brimming with symbolism, primal emotions, ritualistic happenings and a palpable sensuality. And there is no denying that his Medea is a stunning creation greatly aided by Callas’s intense on-screen presence (her face expresses a range of complex emotions without the need for dialogue). Other reasons for experiencing this unique take on the Greek myth include the exotic period costumes of Piero Tosi (The Leopard, Death in Venice), the ethnographic music score arranged by Elsa Morante (featuring the use of Tibetan chants, Balkan choral arrangements and a santur, an Iranian variation on a dulcimer) and the awe-inspiring settings, which include the wind-sculpted landscapes of Goreme National Park in Cappadocia, Turkey, the Citadel in Aleppo, the Campo Santo monument in Pisa and other picturesque Italian locations. All of this is topped off by the art direction/production design of Oscar winner Dante Ferretti (The Aviator, Hugo) in his film debut and the evocative cinematography of Ennio Guarnieri (Vittorio De Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis [1970] and Lina Wertmuller’s Swept Away [1974]).

Some film critics and admirers of Pasolini view Medea as a transitionary work in the director’s career when he became more interested with imbuing his work with political ideology and personal obsessions. In some ways, you could say his Medea is the story of an epic cultural clash between the civilized, more modern world of Jason and the ancient primitive world of Medea or even a battle between rational and irrational forces. Some scholars in recent years even see Medea as a feminist parable in which the heroine justifiably reacts against her husband’s cavalier and dismissive male chauvinist behavior. Others see it as Pasolini’s nihilistic reaction to an unjust universe.

I prefer film critic Tony Rayns’s interpretation of the film which views Pasolini’s movie as a love letter to Maria Callas but also the director’s “most bizarre exploration of Freudian themes through Marxist eyes…Its splendours crystallise in its casting of Callas as Medea, a virtual mime performance with her extraordinary mask of a face bespeaking extremes of emotion; its weaknesses, equally, in the casting of [Giuseppe] Gentile as Jason, blandly butch, whose presence does nothing to fill out an ill-sketched, passive role. But the real achievement is that Pasolini’s visual discourse is every bit as eloquent as the verbal one he puts in the mouth of Terzieff’s centaur.”

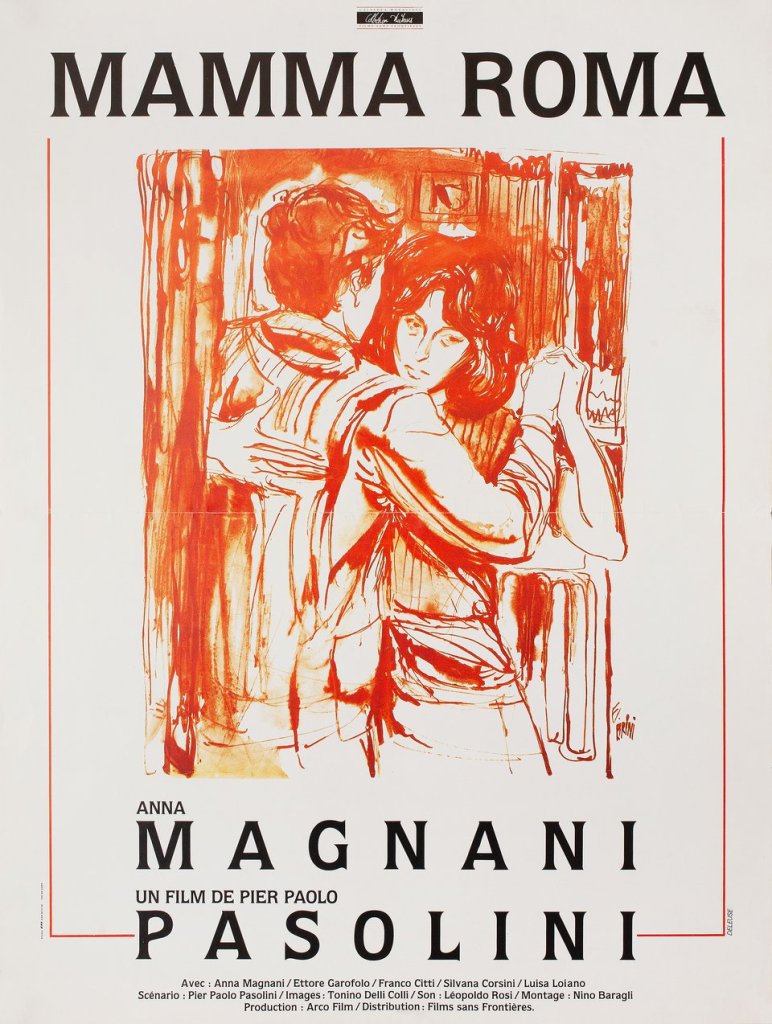

Admittedly, Medea is probably not the best entry point for anyone unfamiliar with Pasolini’s work. A much better starting place for beginners is the director’s early, more accessible work such as his 1961 directorial debut Accattone, the tale of a pimp trying to survive in the slums of Rome, or Mamma Roma (1962), with Anna Magnani as an ex-prostitute trying to make a better life for her son; both of these are essentially melodramas produced long after the Neorealism movement had ended.

In comparison, Medea is a more challenging watch with its experimental approach to narrative and unconventional editing techniques. It should also be noted that while the movie is full of violent acts, most of it is highly stylized and unrealistic, especially the execution of a sacrificial victim toward the beginning of the film and the murder of Medea’s brother.

Still, the film has a rough-hewn poetry that is often enhanced by the astonishing visuals, rich sound design, and the use of mostly non-professional actors plus the usual Pasolini trademarks are on display like his visual fascination with male beauty and physicality. In the role of Jason is Giuseppe Gentile, an Olympic bronze medal champion of the triple jump in his only film. He is clearly a sex object for Medea and served up like a sexy male pin-up.

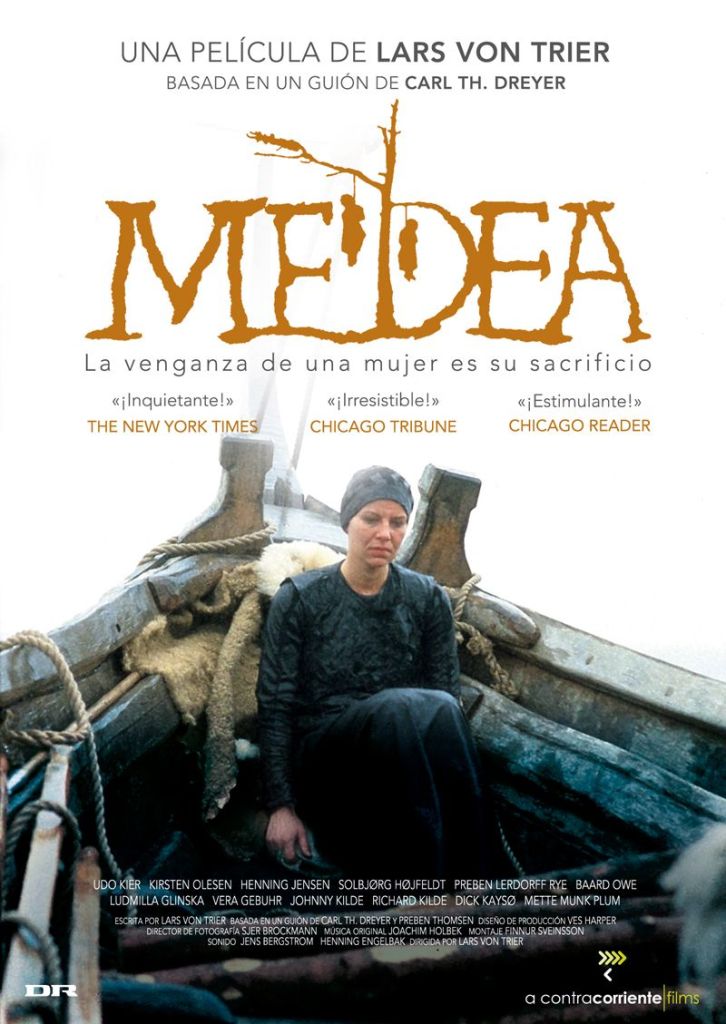

It is also rather curious that Callas never appeared in a singing role on film despite her reputation as a world class diva. After all, there have been operas based on the Medea legend such as one by Luigi Cherubini in 1797 or by French composer Darius Milhaud in 1939. Other adaptations of Euripides’ play include Seneca’s take on the legend circa 50 CE (the time period before year 1), stage productions by playwrights Jean Anouilh and Franz Grillparzer, a 1959 TV version with Judith Anderson in the title role and Lars von Trier’s 1988 film adaptation with Kirsten Olesen and Udo Kier as Medea and Jason.

Pasolini’s Medea has been released in various formats including a Sony Pictures Home Entertainment Blu-ray in July 2016 and The Criterion Collection’s Pasolini 101 collection from June 2023, a 9-film lineup which includes Medea with another Greek myth drama Oedipus Rex (1967) with Franco Citti in the title role. Possibly the best option for those who want to purchase the film is the BFI Blu-ray edition which presents the movie in both Italian and English language versions with optional subtitles (you need an all-region player to view it). You should also be aware that Pasolini filmed the movie without direct sound so that he could later dub his international cast in post-production which explains why the dubbing is not always well-synced or even the voice of the featured actor on screen.

Other links of interest:

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/8186-the-elegiac-heart-pier-paolo-pasolini-filmmaker

https://www.screenslate.com/articles/medea

https://www.talkclassical.com/threads/maria-callas-recorded-legacy.33051/page-263

https://www.olympedia.org/athletes/71991