What are the circumstances that lead to the formation of a new film movement? For the pioneers of the neorealism movement in Italy, it was the need to address the problems of the country in the aftermath of WW2 when commercial films seemed irrelevant in comparison. In France during the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was the desire by the Nouvelle Vague filmmakers to break away from the aesthetics of studio made films in favor of new and more relevant subject matter and production methods. And, in Brazil during this same time period, it was also a generational response by young filmmakers to their country’s cinema, which became known as the Cinema Novo movement. Yet, it wasn’t just a revolt against the traditional commercial movies of Brazil but an effort to address, discuss and critique aspects of the country’s national identity on the world stage. Cinema Novo (2016), a documentary by Eryk Rocha (son of director Glauber Rocha), is a non-traditional approach to the genre which immerses the viewer in a visual and aural whirlwind that captures the power, passion and creativity of the movement. The Hollywood Reporter called it “a pure bombardment of the senses” and that’s a compliment.

If you are looking for a more traditional documentary approach that chronicles a historic film movement with all the featured clips and talking heads clearly identified, this is not it. Yes, some movies and interviewees are clearly credited, but often a montage of scenes from various films unfold as the voiceover by an unidentified pioneer of the Cinema Novo movement provides the context to what you are seeing. What is important is that Rocha’s Cinema Novo weaves together archival interviews, behind the scenes footage and movie clips in such a poetic and artful fashion that even those unfamiliar with Cinema Novo will come away from the experience eager to learn more. (The closing credits of the documentary lists the titles and directors of all of the more than 50 clips represented).

Prior to the 1950s, Brazilian cinema was relatively unknown outside its own country with few exceptions. One of these was Mario Peixoto’s Limite (1931), a stunning avant-garde work that is now considered a landmark in the development of Brazilian cinema. Director Humberto Mauro and Alberto Cavalcanti also served as inspirations to future generations of Brazilian filmmakers. Mauro’s 1933 melodrama Ganga Bruta was highly innovative for its fusion of Soviet montage and German expressionism and Alberto Cavalcanti’s O Canto do Mar (English title: The Song of the Sea, 1953) could be seen as a prototype for the Cinema Novo films to come with its devastating portrait of migrants trying to survive in the drought-ridden Northeastern region of Brazil.

Cavalcanti was of particular interest to the Cinema Novo filmmakers because he had left Brazil in 1920 to pursue a film career in France. His debut film was Rien Que les Heures (English title: Nothing But Time, 1926), a dawn-to-dusk documentary portrait of Paris, and he eventually moved to the U.K. where he helmed such famous films as Went the Day Well? (1942), The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1947) and I Became a Criminal aka They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), a British noir with Trevor Howard. Even more significant was Cavalcanti’s return to Brazil in 1950 when he prefigured the Cinema Novo movement with such films as The Song of the Sea and the 1954 romantic drama Mulher de Verdade (English title: A Real Woman).

Shortly after this, the Cinema Novo movement begin to take shape under the pioneering efforts of Nelson Pereira dos Santos whose Rio, 40 Degrees (1955), a semi-documentary on the street people of Rio de Janeiro, was a preview of the subject matter and the aesthetic trademarks from the emerging movement. It was a time of major transition in the Brazilian film industry and Santos and his contemporaries created a new cinema that focused exclusively on their country’s history, identity, and culture as well as the national problems that weren’t being addressed by the government – poverty, exploitation of the working class, religious and political persecution, the mistreatment of indigenous people, environmental concerns (the destruction of farming communities through drought and the deforestation of the Amazon) and other controversial topics.

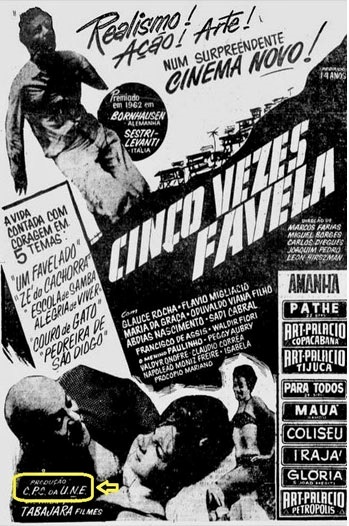

Other milestone works appeared in the late 1950s such as Santos’ Rio, Zona Norte (1957), a musical drama featuring samba music, Roberto Pires’s crime drama Redencao (1959), Patio (1959), an experimental short by Glauber Rocha that utilizes the game of chess as a visual motif, Arraial do Cabo (1960), a portrait of a fishing community in transition by Mario Carneiro and Paulo Cesar Sarceni and Jean Mitry’s avant-garde short La Grande Foire aka The Big Fair (1961). But it wasn’t until 1962 that the Cinema Novo movement exploded in a creative frenzy launching the careers of Miguel Borges, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Marcos Farias, Leon Hirszman and Carlos Diegues with the five-part anthology film Cinco Vezes Favela aka 5 X Favela which showcased dramatic snapshots of life in the slums of Rio de Janeiro. It was Andrade’s unsettling episode, Couro de Gato (Cat Skin), a tale of ghetto boys hunting stray cats for their skin, that set the tone and approach of the entire project with its critique of the predatory structure of Brazilian society.

Ruy Guerra, director of the landmark political drama Os Fuzis (English title: The Guns, 1964), in which government troops terrorize rural villagers, states in the documentary that he and his fellow filmmakers realized “it was the collective awareness that human problems weren’t individual but a part of a specific moment in history” along with an “awareness that Brazil is part of the third world.”

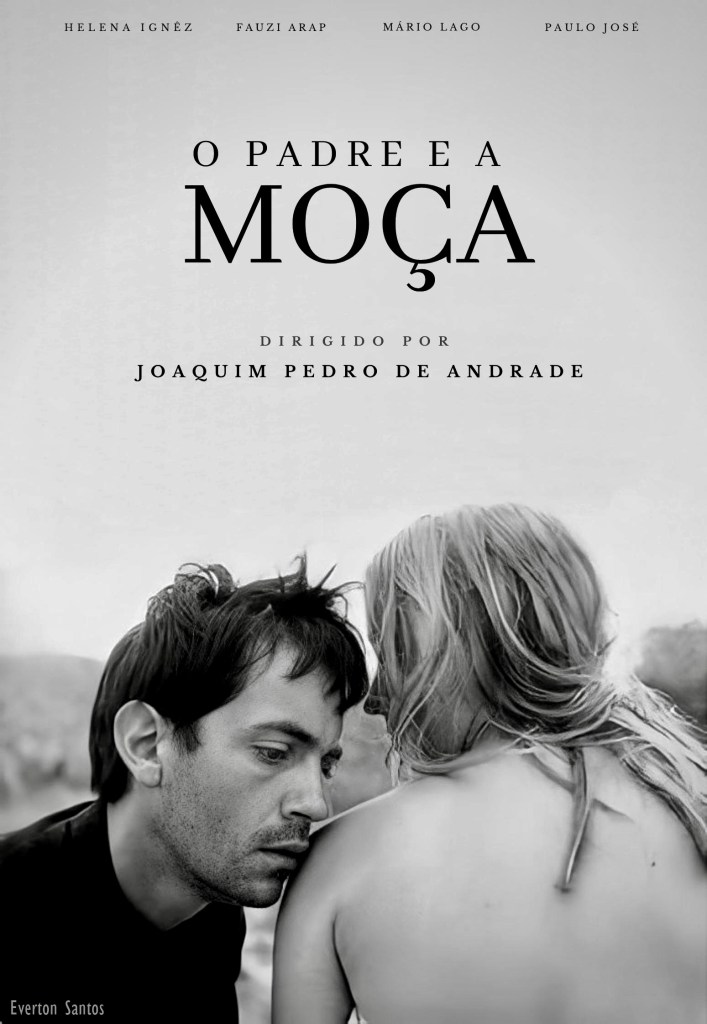

One of the pleasures of watching Cinema Novo is to marvel at the dazzling black and white cinematography of so many cameramen like Mario Carneiro, Jose Medeiros and Helio Silva, who adapted some of the techniques of the neorealism and Nouvelle Vague movements such as using natural light, hand-held cameras, authentic locations and innovative camera angles. These stylistic choices are all on display in cinematic gems like O Padre e a Moca (English title: The Priest and the Girl, 1966), a tale of forbidden love, and Leon Hirszman’s A Falecida (English title: The Deceased, 1965), a black comedy about a woman with a death obsession. The latter was an early starring role for Fernanda Montenegro who was later nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for her performance in Walter Salles’s Central Station (1998), one of the best Brazilian films of the nineties.

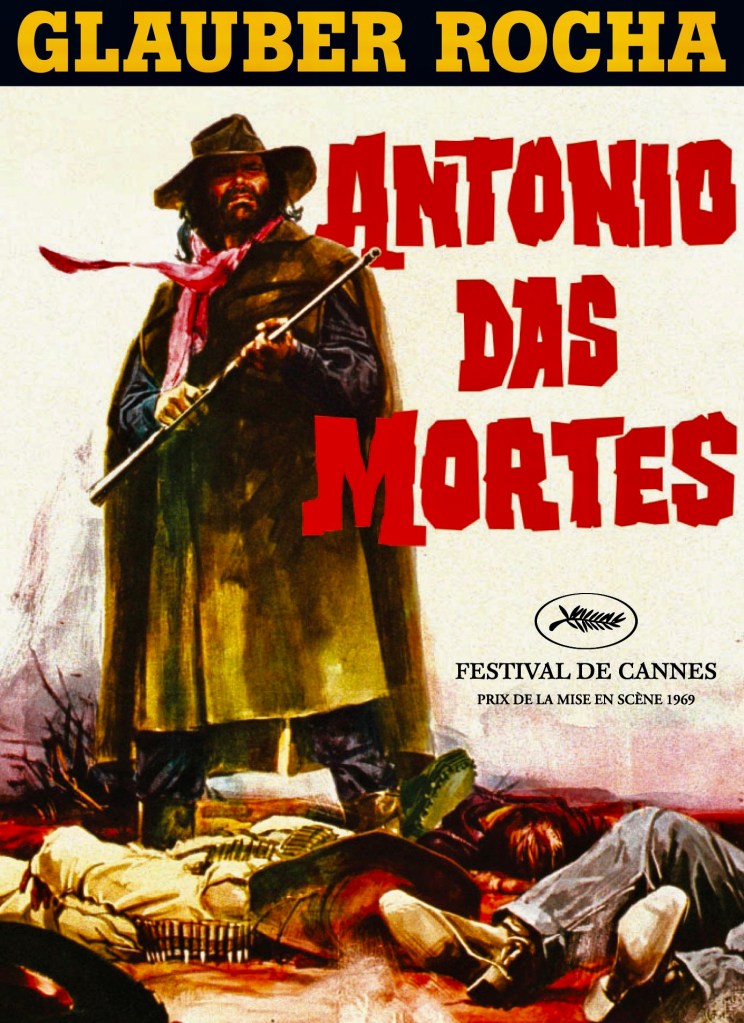

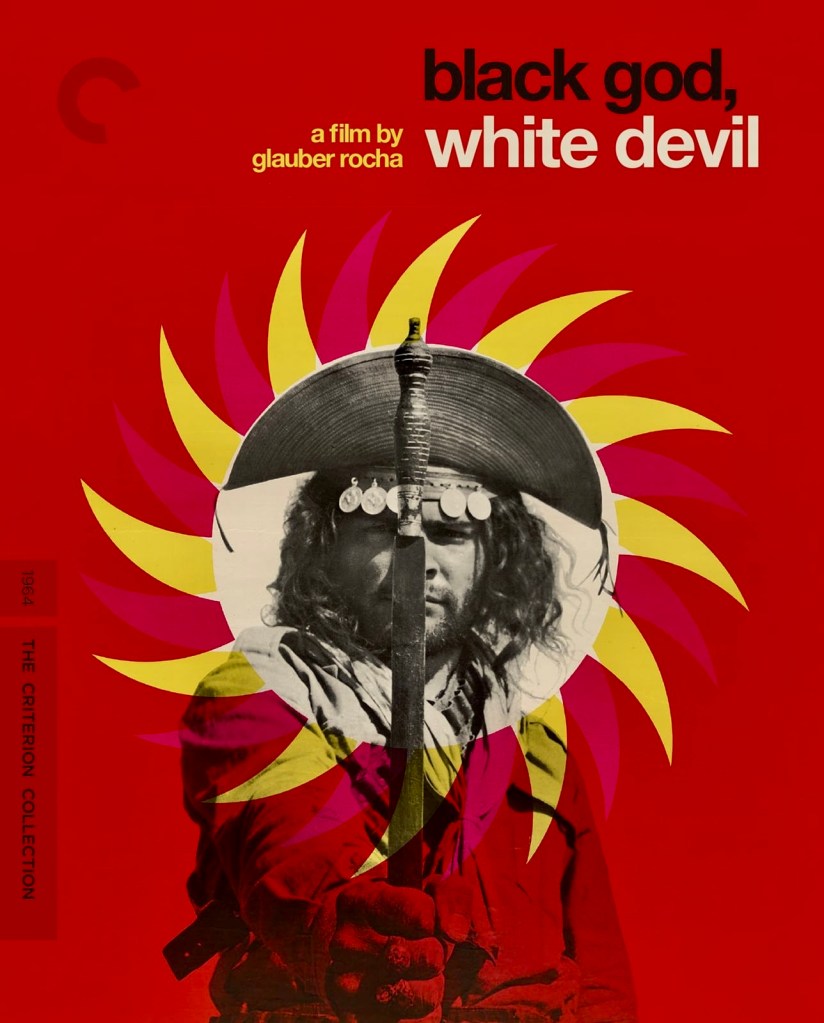

1964 proved to be a banner year for Cinema Novo as Santos’s Vidas Secas (English title: Barren Lives), Rocha’s existential western Black God, White Devil and Diegues’s Ganga Zumba, a historical drama about an outlaw community of runaway slaves, were all featured at the Cannes Film Festival with Rocha and Santos being nominated for the Palme d’Or. Italian and French film critics were especially enamored of the Cinema Novo movement and Paulo Cesar Saraceni’s Porto das Caixas (1963) and Guerra’s The Guns were equally popular in Europe but these films never really achieved the same level of attention and acclaim in the U.S.

Even in their own country, the Cinema Novo filmmakers did not really appeal to mainstream audiences despite the positive support of Brazilian film critics. The reality is that movie audiences are basically the same everyway – they want escapism when they go to a film. Can you imagine someone from the Brazilian working class like a bricklayer, maid or miner preferring to watch something like Barren Lives, a bleak tale of a homeless farming family looking for work, over a James Bond action-adventure or a “chanchada,” a Brazilian form of musical comedy?

As a consequence, the Cinema Novo filmmakers had difficulty finding distribution and audiences for their films and when a military dictatorship took over the government in 1965, the movement began to die a slow death, hastened by censorship and in some cases, political suppression. Rocha, for example, ended up fleeing the country since he no longer had the freedom or resources to exercise the sort of creative control he enjoyed in 1964. It should also be noted that the Cinema Novo movement was dominated by men without one female director in the bunch.

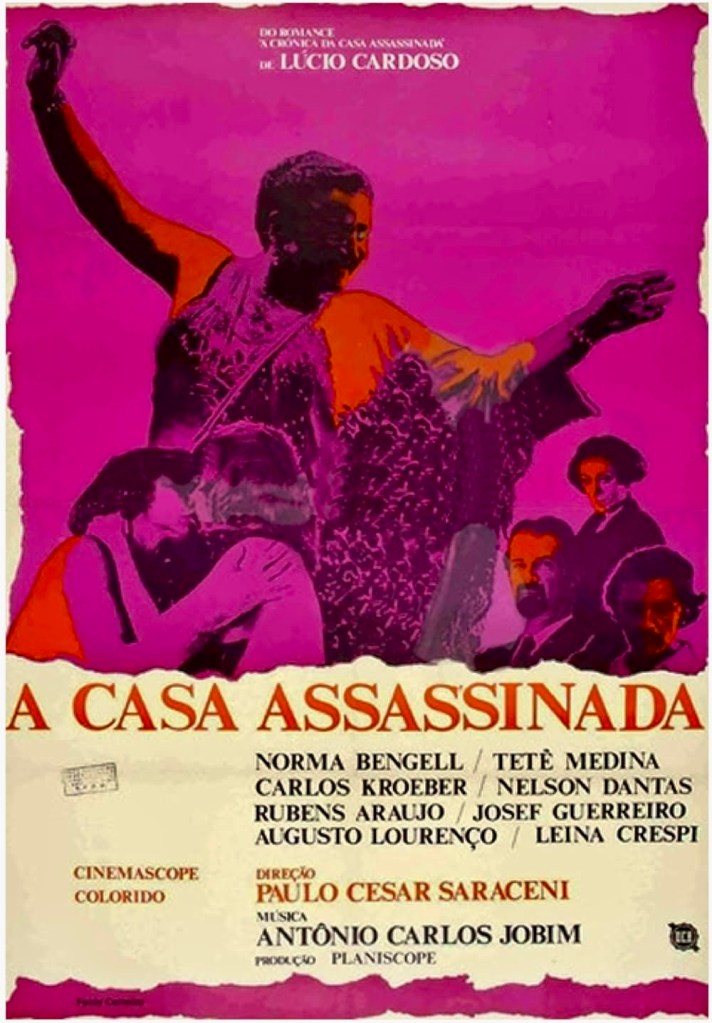

There were still some key works created in the movement before it came to an end in the early 1970s such as A Casa Assassinada (English title: The Murdered House, 1971), a moody psychological drama about a dysfunctional family directed by Paulo Cesar Saraceni, and Santo’s How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman (1971), a satire of colonialism in which the Tupinambas Indians of Brazil turn the tables on their former conquerors. But these films were able to avoid the close scrutiny of the censors because they were not overtly critical of the government or controversial in nature at first glance. Yet, if you look closely, you can see subversive elements and sly critiques of Brazilian society lurking just beneath the surface.

All of the above films mentioned can be glimpsed as clips in Cinema Novo along with samples of other work by directors as diverse as Anselmo Duarte, Geraldo Sarno, Gustavo Dahl, Luiz Carlos Barreto, Roberto Farias, Alex Viany and others. And the music score by Ava Rocha (daughter of Glauber Rocha) is a pulsating and exotic accompaniment to the sensory experience (Ava even performs the song “Oh Mana Deixa Eu Ir” on the soundtrack).

Cinema Novo received a brief, limited theatrical release in the U.S. but it had better luck in Europe where it received the Golden Eye award at Cannes and picked up additional prizes at Brazilian film festivals. The documentary was released on DVD by Icarius Films in September 2017 but an even better option is to purchase the Criterion Collection edition of Black God, White Devil on Blu-ray, which includes a beautifully remastered version of Cinema Novo as an extra feature.

Other links of interest:

https://www.bfi.org.uk/lists/10-great-brazilian-films

https://cinecollage.net/cinema-novo.html