If you look up the word melodrama in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the description reads “a work (such as a movie or play) characterized by extravagant theatricality.” The Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries offers a similar definition: “a story, play, or novel that is full of exciting events and in which the characters and emotions seem too exaggerated to be real.” Some popular examples of this in the movies would have to include The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), The Barefoot Contessa (1954) and The Best of Everything (1959). But they are some films in this category that are so excessive in tone and style that they belong in their own category of extreme melodrama. Among the more glaring examples of this are Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956), The Caretakers (1963), which is set in a psychiatric hospital where Joan Crawford teaches karate, the Tinseltown expose The Oscar (1966), and four films – yes, four! – from director King Vidor: Duel in the Sun (1946), Beyond the Forest (1949) with Bette Davis, Ruby Gentry (1952) starring Jennifer Jones, and my personal favorite, The Fountainhead (1949), which scales dazzling heights in operatic excess.

Pauline Kael called it “a little delirious and definitely skewed…It’s an extravaganza of romantic, right-wing camp.” And David Thomson’s assessment is dead on: “It’s like looking at the first film ever made. You can believe this is primitive cinema in which psychic thrust lies naked in the imagery, like a sword in a bed. There is no inhibition, and the viewer settles in after a few minutes. The exaggeration relies on the constant, penetrative accuracy of the imagery…The film ravishes us. We might cry rape, but we have paid our money.”

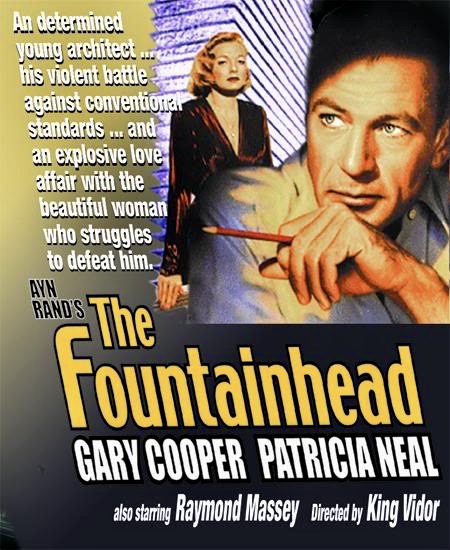

Considering the time it was made, it is hard to imagine a more unlikely candidate for a screen adaptation than Ayn Rand’s best-selling novel, The Fountainhead, which espoused her philosophy of Objectivism, a belief in the integrity of the individual and a general contempt for the mediocre standards accepted by the masses.

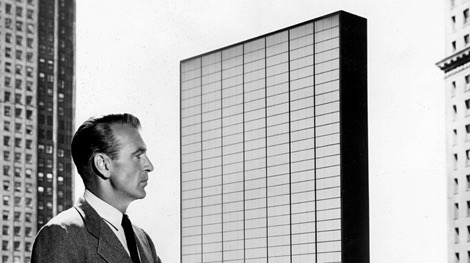

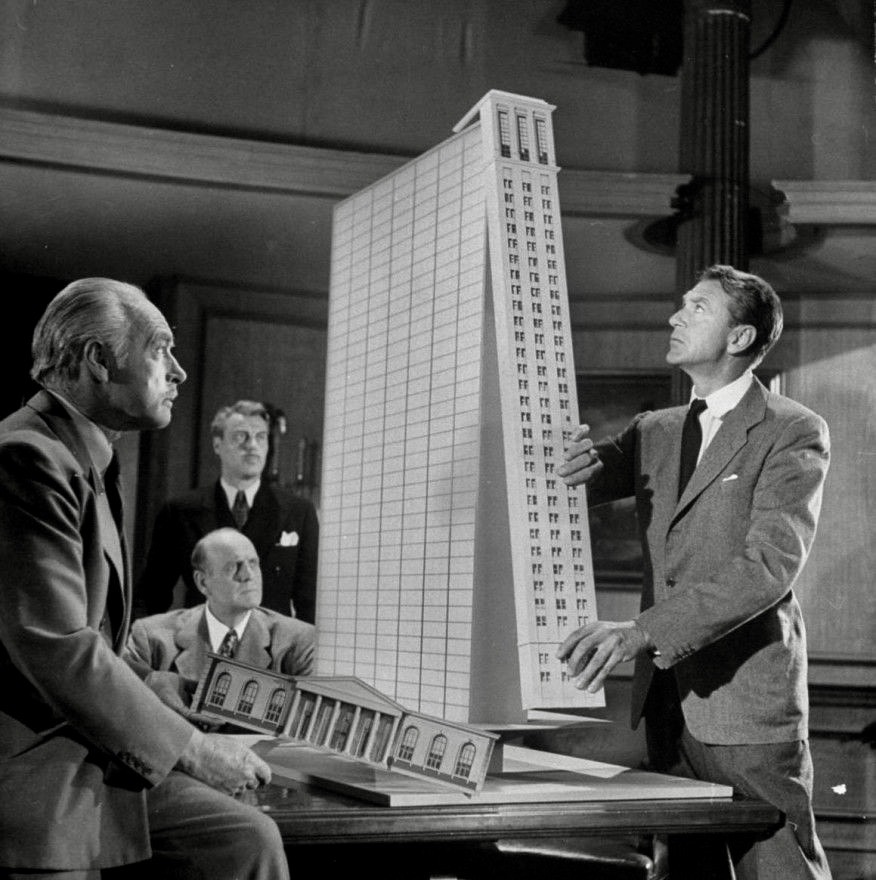

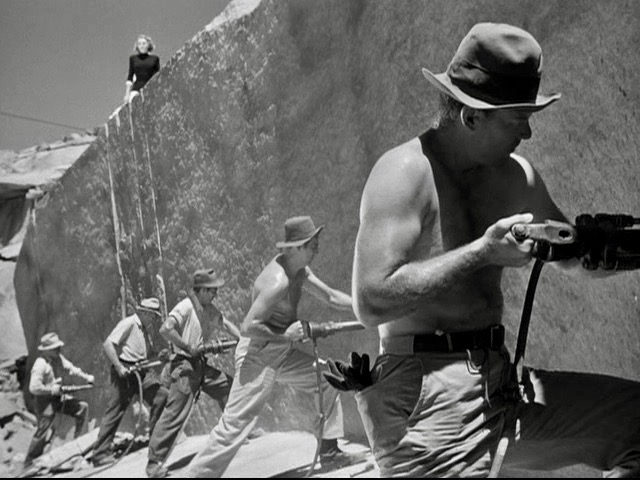

The hero of the novel is Howard Roark, an architect who designs buildings for his own aesthetic reasons. When his most ambitious project – a housing project design – is altered from his original plans, he refuses to accept this perversion of his work and proceeds to dynamite the building. The 1949 film version, based on Ayn Rand’s screenplay of her novel, preserves her didactic dialogue while placing the main characters, essentially symbolic stand-ins for opposing ideologies, amid large, artificial sets designed by Edward Carrere who was heavily influenced by German Expressionism. Needless to say, audiences were puzzled, angered, or unintentionally amused by this one-of-a-kind oddity…but I doubt anyone was bored.

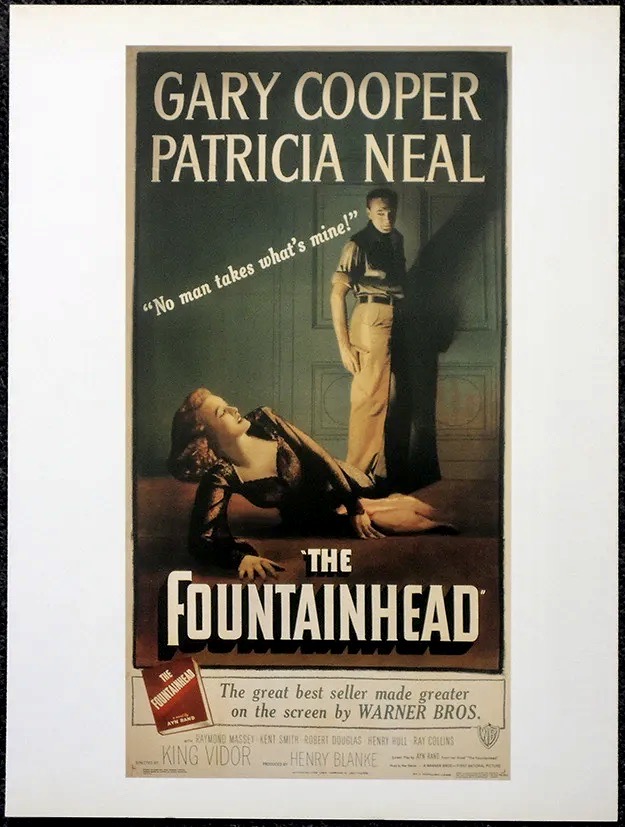

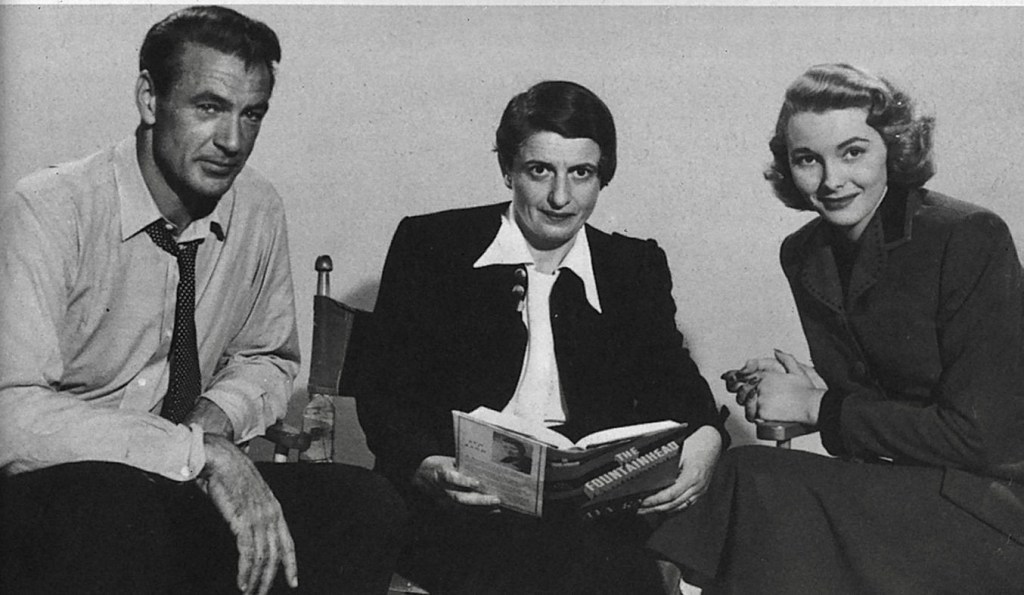

No one who saw the film, however, could deny the sexual chemistry between Gary Cooper as Roark and Patricia Neal, in her second film role, as Dominique Francon, the strong-willed daughter of a renowned architect. Off screen, Cooper and Neal embarked on a long, passionate affair during the making of this film, despite the fact that Cooper was 47 and married and Neal was only 22 years old.

In the biography, Coop by Stuart M. Kaminsky, director King Vidor said, “I remember the day we drove up to Fresno to do our location shooting for The Fountainhead. We met Patricia Neal there that night. It was the first time they had met. They went for each other right away. After dinner we never saw the two of them again except when we were shooting.”

While there are various accounts of who originally initiated the film version of The Fountainhead, it’s clear that neither Cooper nor Neal were the original choices for the lead roles. When the book first appeared in print, Barbara Stanwyck connected strongly with the central characters and strongly urged Warner Bros. mogul Jack Warner to purchase the rights. She even approached the author about appearing in the film version but Rand told Stanwyck that she had written the Dominique character for Greta Garbo. Nevertheless, Warner purchased the book, Mervyn LeRoy agreed to direct, and Humphrey Bogart was cast as Roark and Stanwyck as Dominique.

Unfortunately for Stanwyck, the project, which was being prepared during the final days of World War II, was delayed due to a wartime restriction. The climactic scene where Roark dynamites his creation was forbidden on the grounds that demolishing scarce housing stock amounted to despoiling strategic materials. After the war was over and the restrictions lifted, Warner rethought the casting and direction, replacing his original choices with Cooper and Neal and King Vidor (as director). Learning she had lost the role to a younger actress, Stanwyck fired off an angry telegram to Warner expressing her bitter disappointment and terminated her contract with the studio.

Stanwyck wasn’t the only one unhappy with the casting. Vidor recalled, “I didn’t think that Cooper was well cast but he was cast before I was. I thought it should have been someone like Bogart, a more arrogant type of man. But after I forgot all that and saw it several years later I accepted Cooper doing it.” Even Coop himself was uneasy about his performance in the film and would often say in interviews about The Fountainhead, “Boy, did I louse that one up.”

Casting aside, there were other compromises made on the way to production. Vidor contacted Frank Lloyd Wright about executing Roark’s designs for the film and the famous architect agreed for his standard 10 percent commission based on the entire budget of the film. Jack Warner balked when he heard this news and forbid Vidor from further negotiations with Wright, fearing a potential lawsuit if they used Wright’s designs.

Another potential problem involved the Breen Office, which objected to the frantic coupling of Cooper and Neal on-screen and had the writers change the erotic one-night-stand between Roark and Dominique to a rape scene.

The Fountainhead, despite its shortcomings as a film adaptation of the book, remains a fascinating curiosity in the history of American film. Its righteous view of capitalism and morality place it firmly in the pantheon of right-wing conservative cinema while the on and off-screen relationship between Cooper and Neal reminds one that life imitates art so often in the film industry.

Every aspect of the production is striking from Robert Burks’s black and white cinematography and Edward Carrere’s art direction to the dramatic score by Max Steiner and an outstanding supporting cast that includes Raymond Massey, Kent Smith, Robert Douglas, Henry Hull, Ray Collins, Jerome Cowan and Moroni Olsen. And nobody in real life talks like the characters in The Fountainhead with Gary Cooper’s Roark often erupting into lengthy diatribes expressing Rand’s philosophy like this one: “Our country, the noblest country in the history of men, was based on the principle of individualism. The principle of man’s inalienable rights. It was a country where a man was free to seek his own happiness, to gain and produce, not to give up and renounce. To prosper, not to starve. To achieve, not to plunder. To hold as his highest possession a sense of his personal value. And as his highest virtue, his self respect. Look at the results. That is what the collectivists are now asking you to destroy, as much of the earth has been destroyed.”

Vidor’s film continues to amaze and entertain movie lovers with its larger-than-life qualities. Some consider it a trash masterpiece and contemporary film critics continue to ponder to its unique blend of stylized art direction and extreme melodrama such as Terence Rayns of TimeOut magazine who wrote “The most bizarre movie in both Vidor’s and Cooper’s filmographies, this adaptation of Ayn Rand’s first novel mutes Ms Rand’s neo-Nietzschean philosophy of ‘Objectivism’ but lays on the expressionist symbolism with a ‘free enterprise’ trowel…. As berserk as it sounds, although handsomely shot by Robert Burks and directed with enthusiasm.”

The Fountainhead has been released in various formats over the years such as the Warner Brothers DVD set, Gary Cooper – The Signature Collection, which packages the film with four other Cooper movies including Sergeant York. It has also appeared as a single DVD from the Warner Archives but the movie cries out for a Blu-ray upgrade with extra features.

*This is a revised and expanded version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

Other links of interest: